Highlights

- The combination of U.S. tax cuts and increased government spending will worsen the deficit amidst an expanding economy, when the government’s revenue base is typically at its best. This begs the question: what will government finances look like when the next recession hits?

- We answer this question by designing an economic recession scenario. Even though the magnitude of our recession is nowhere near the scale of the 2008 financial crisis, deficit levels actually approach that period. This adds to a debt burden that was already set to rise thanks to a structural deficit.

- Given America’s unique status as the preeminent global reserve currency, a worsening fiscal scenario in a recession is unlikely to trigger a fiscal crisis, as it might for an emerging market. But, it will exact an economic and political toll.

- These larger deficits make it more difficult for political leaders to apply fiscal stimulus to counteract the recession effects on household and corporate income. Likewise, the worsening debt burden can restrain the pace of economic recovery.

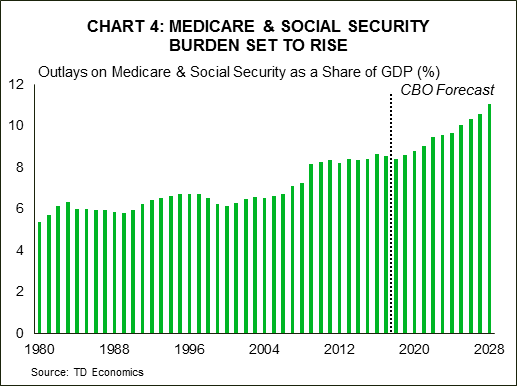

- Higher debt service costs plus expanding demographic pressures for Medicare and Social Security will take a larger share of government coffers, leaving less room for the federal government to spend on other priorities.

The biggest change to the U.S. economic outlook over the past six months has been the double-dose of fiscal stimulus from Washington: first tax cuts, then a large two-year boost to government spending (BBA18). We have discussed the impact of these measures (see here and QEF), alongside the concern of deliberately creating larger deficits in good economic times. Now, we explore what has become an increasing curiosity among our clients: what could happen to U.S. government finances when the next recession hits? To be clear, this is scenario-based analysis and we are not forecasting a recession in our two-year outlook. But, it’s well documented that this economic cycle is long in the tooth, and this typically brings a greater risk of a build-up in excesses and greater sensitivity to changes in policy.

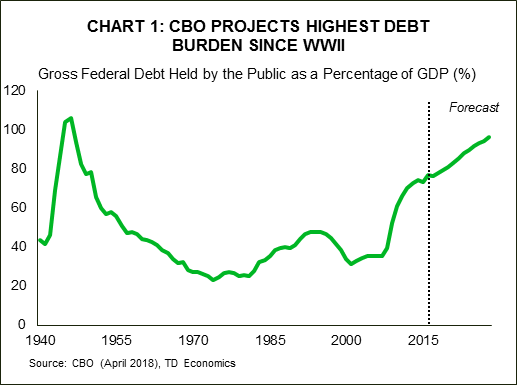

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that the combination of tax cuts and increased spending would grow the deficit from 3.4% of GDP in 2017, to over 5% by 2022. The combination of larger deficits and an increasing burden of Medicare and Social Security due to population aging causes the debt-to-GDP ratio to hit the highest level since 1946 (see Chart 1). These projections assume a consistent period of economic growth, averaging 2.2% in real terms (4.3% nominal) over the next five years. So that’s just the starting point of an economy that maintains an uninterrupted expansion. Now, lets look at some possibilities in the event that a recession occurs in this time frame.

Stress testing the deficit

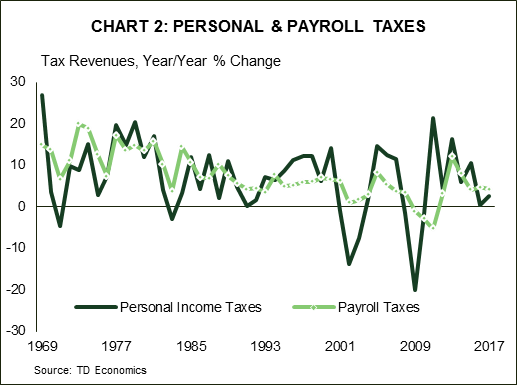

It’s no stretch of the imagination to state that government finances worsen in a recession, as tax revenues collapse and government “automatic stabilizer” expenses kick in, such as unemployment insurance benefits and food stamps (see Chart 2). These typical experiences through history inform us of the backdrop to our recession thought-experiment.

We modelled our recessionary scenario off the Federal Reserve’s adverse scenario from its recent stress test exercise (referred to in short as CCAR). However, we needed to make an alteration with regards to timing, by pushing forward the starting point of the recession by two years (to Q1 2020). We chose to start the recession in 2020 for the simple reason that we needed to pick a starting point and there is no indication at present among the economic indicators that a recession rests within the immediate forecast horizon. The recessionary scenario lasts six quarters and real GDP falls roughly 3¼% from peak-to-trough. The unemployment rate rises steadily from 3.7% at the end of 2019, to peak at 7.3% in the fourth quarter of 2021. As a point of reference, the decline in real GDP is amounts to only three-quarters of the 2008 experience.

To incorporate the fluctuations in government revenues that will be coming on stream due to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), we then overlay the difference between our baseline revenue forecast and our recessionary scenario relative to the CBO’s current base-case fiscal forecast from April 2018 for the next ten years. We do the same exercise on the spending side.

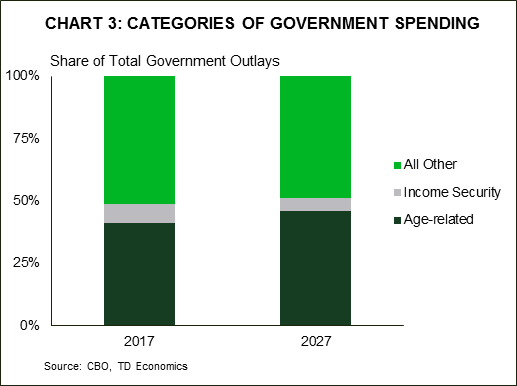

However, estimating changes in spending are more nuanced than revenues. There are a few moving parts to consider. Certain spending items are more cyclical than others, but don’t necessarily bear the largest weight on government coffers. For instance, income security spending on programs like unemployment benefits and SNAP (food stamps) are highly related to the economic cycle, but make up quite a small share of overall government spending (see Chart 3). In contrast, spending on Medicare and Social Security rises inexorably, but this is largely related to the aging population rather than the cyclical downturn (Chart 4). The remainder of spending, which includes defense, Medicaid and all other federal government spending, varies largely due to political decisions, with no discernible relationship to the economic cycle. Therefore, determining what would happen to this portion of government spending relative to the current CBO baseline carries more judgement than the revenue side of the ledger.

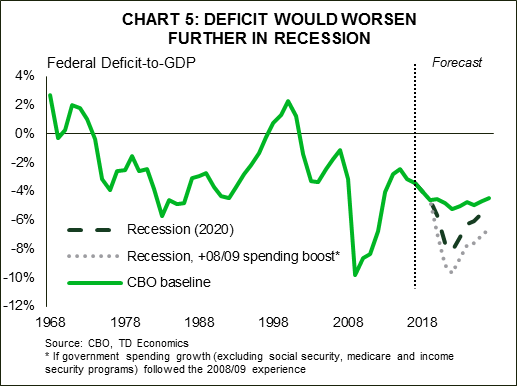

Summing it all up, the deficit-to-GDP trough worsens from the 5.2% in the CBO’s baseline projection, to roughly 8.1% by 2022 (see Chart 5). This would mark the largest deficits outside of the global financial crisis. In other words, although the recession is far less severe than the Great Recession, the size of government deficits would almost equal its stature. This is a purely forecasted result based on the behavior of government finances during past recessionary periods. It does not include a decision by Washington to either ramp up discretionary spending more than the historical experience, or likewise to cut back on spending given ballooning deficits. Either scenario would largely depend on the political situation at the time. If we assume that the government would come under political pressure to stimulate the economy similar to that seen in 2008-09, the deficit would indeed approach the depths reached in 2009 at 10%.

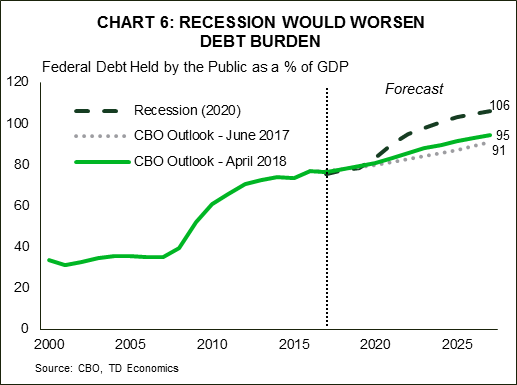

It’s natural to assume that a recovering economy will automatically minimize and eventually eliminate the deficit. However, there are two obstructions that become magnified in the future relative to post-2008. The first is that the population is a lot older, and this makes it more difficult to shrink a deficit in the absence of active policy with the explicit intent of doing so. The government’s tax base will reflect the reality of a labor force slowing to a mere 0.5% within the next five years, the period in which a recovery would be in full swing. The second is a heftier debt burden relative to the current cycle. Even in the event the budget returns to balance, the stock of debt from past deficits remain. The compounding effect of deficits would increase the debt-to-GDP ratio by 11 percentage points above the CBO’s current baseline in 2027 (see Chart 6). In its recent report, the CBO makes a point to highlight the risks from the higher debt burden from fiscal stimulus. Additional debt built-up due to a recession would only heighten these risks.

Fiscal Space: Use it if you’ve got it

An economic forecast can tell you how a recession might impact the deficit. But, it isn’t in an economist’s tool box to predict how political leaders would respond. In an ideal world, governments would ramp up spending in areas like infrastructure, to help counteract the impact of a recession, at the expense of larger deficits in the short-run. But, it is reasonable to think that it will be politically more difficult to do this during the next recession, when deficits are approaching depths not seen since the global financial crisis, while debt levels march to unprecedented levels.

That tendency has in fact been born out in recent work by Romer and Romer (Christina D. Romer, 2012), which showed that economies with less monetary and fiscal policy space have more severe recessions after a financial crisis. While both monetary and fiscal policies are important in how a country fares after a financial crisis, their results indicate that fiscal policy space edges out in importance.

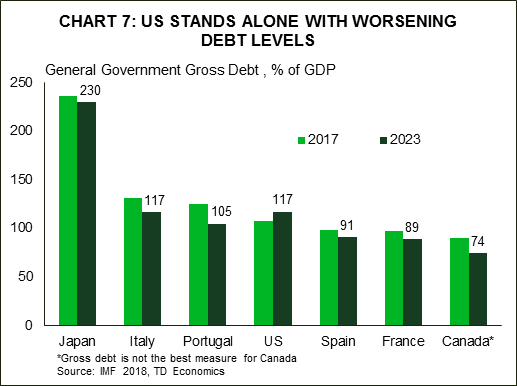

Their research also shows that low fiscal space (which in their sample are countries with debt levels more than one standard deviation above the mean debt-to-GDP level, which was 96%) is associated with worse outcomes following a crisis. These countries had deeper recessions than countries that have fiscal space. This is not so surprising, as countries with high debt loads are often forced into fiscal consolidations after a crisis because investor nervousness makes it harder to borrow. A good real world example of this was Italy. Prior to the financial crisis, Italy’s debt-to-GDP ratio was about 100%, and Italy’s sub-par recovery after the financial crisis can almost entirely be accounted for by its lack of fiscal space. Japan in 1997 had a similar experience.

These findings are specific to a financial crisis, and the next U.S. recession may not take that form. It could certainly be more moderate, and odds favor this outcome given the degree of banking oversight that has come out of the 2008 episode. And, the research does not specifically outline whether it is the perception of policymakers or actual rising borrowing costs that results in less fiscal stimulus being used in countries with a higher debt load.

Importantly, the U.S. differs from Italy and Japan in a distinct way. It is the world’s reserve currency, and the U.S. Treasury market has been treated as a global safe haven, that is, so far. Should this hold, the U.S. won’t necessarily face a spike in borrowing costs as a penalty imparted by investors for worsening deficits. This is the concept of exorbitant privilege. However, the U.S. is increasingly looking like Italy, in another respect – its debt burden. The IMF recently released updated fiscal projections across countries showing that the U.S. stands alone among major economies with a worsening debt burden over the next five years (Chart 7). Privilege still comes with responsibility.

Higher debt burdens exact a toll

Even without a market-driven fiscal crisis, there would still be political and economic costs to absorb. First, the political landscape could make it difficult to engage in a great degree of fiscal stimulus. In turn, this could slow the timing of the economic recovery, or mute the magnitude of growth. Second, there would likely be some penalty imparted to Treasury yields from higher debt burdens that ultimately leads to a flood of supply. Our analysis indicates that the worsening path of the deficit shown in Chart 6 would result in the 10-Year Treasury yield being 25 basis points higher than otherwise.

Third, we cannot rule out a debt downgrade, or perhaps a negative watch, depending on how rating agencies viewed the prospects for the economic outlook and fiscal discipline. Ratings agencies last put the U.S. government on a negative ratings watch in 2013, and downgraded U.S. debt in 2011, both episodes occurred after a debt ceiling standoffs. The ratings agencies argued these down to the wire standoffs undermined the confidence of the U.S. dollar as the preeminent global reserve currency, by casting doubt over the full faith and credit of the U.S. These risks could crop up again if Congress is divided when dealing with fiscal decisions in the next recession, and similar standoffs could shake market confidence.

Finally, the recovery phase would likely be muted by the simple fact that the government will not only be dedicating a greater share of their tax revenues to paying their debt, but they would also need to demonstrate fiscal restraint on spending as revenues recover, given the high deficits. This is the situation outlined by Romer and Romer (2017).

The elephant in the room

The results of the stress test of U.S. government finances put a sharper focus on the already worsening fiscal outlook presented by the CBO in April. But the elephant in the room is the fact that debt burdens are set to rise as far as the eye can see thanks to a budget that doesn’t return to balance over the next ten years, despite a growing economy. In effect, this is the “best case scenario” which hardly seems so. This paper has not addressed what might be done to put U.S. finances on a more sustainable path. These ideas were put forward by the Simpson Bowles Report in 2010, but never adopted. That is because the sort of changes required to eliminate the structural deficit, such as cuts to entitlement benefits or other revenue raising measures, will be politically difficult and will exact a drag on the economy.

To give an idea of the size of the changes required, recent work from the Brookings Institute (Alan J. Auerbach, 2018) estimated that to keep the debt-to-GDP ratio constant would require immediate and permanent spending cuts or tax increases totaling 4% of GDP. That is equivalent to a 21% cut in non-interest spending, or a 24% increase in revenues relative to current levels. The recent fiscal stimulus raises the deficit by slightly more than 2% of GDP in 2019. Therefore, the required fiscal course correction would be roughly twice as big, and in the opposite direction as the recent fiscal stimulus. The precise size of the fiscal drag would depend on how quickly the budget is brought back to balance, and the mix of spending cuts and tax increases enacted to get there. Given the recent stimulus boosted our real GDP growth forecast by 0.5 and 0.7 percentage points in 2018 and 2019 respectively, the economic drag could be significant.

That makes it easier to see why the necessary changes are so politically difficult. However, the longer policymakers wait to make changes to the fiscal trajectory, the more painful the adjustments will be. And, it will be difficult to make that adjustment without making changes to age-related entitlement spending, which looking back at Chart 3, is over 40% of the total.

The Bottom Line

By undertaking significant fiscal stimulus at a time of full employment, the federal government has significantly increased downside risks to the economy over the medium term. Our stress test simulation shows that the next recession could trigger deficits approaching those seen during the global financial crisis. This could constrain the degree to which governments use fiscal policy to lessen the recessionary effects on households.

Finally recession-elevated deficits may be temporary, but their impact on the debt burden is long-lasting. A higher debt burden raises longer-term borrowing costs. This would occur at the same time as age-related entitlement spending on Medicare and Social Security is poised to accelerate leaves even less flexibility for the federal government to spend on other priorities. It could also mean the government may feel pressure to return to fiscal restraint given the heavy debt burden, which would dampen the economic recovery.

Turning this rubik’s cube over and over causes all sides to match. America’s dependence on the kindness of foreign investors will rise over time, and America’s economic growth prospects will incorporate tough choices.

Bibiliography

- Alan J. Auerbach, W. G. (2018). The Federal Budget Outlook: Even Crazier After All These Years. Washington, D.C.: Tax Policy Center.

- Christina D. Romer, D. H. (2012). Phillips Lecture – Why Some Times Are Different: Macroeconomic Policy and the Aftermath of Financial Crises. Economica, 1-40.