Summary

Over the past 15 years, trade policies implemented by countries around the world have led to economic fragmentation and deglobalization. Tariffs come to mind as the instrument disrupting trade integration the most; however, evidence suggests changes to tariff policies may have actually supported global trade cohesion, at least since the Global Financial Crisis in 2008-2009. Regardless, Trump 2.0 trade policy proposals could flip that narrative in a significant way, leading to a more deglobalized world and trade fragmentation. But while the impact on the real economy could be severe, global financial markets seem to be more comfortable digesting tariff headlines and more harmful trade policies.

Trump 2.0 & Rising Restrictive Global Trade Policy

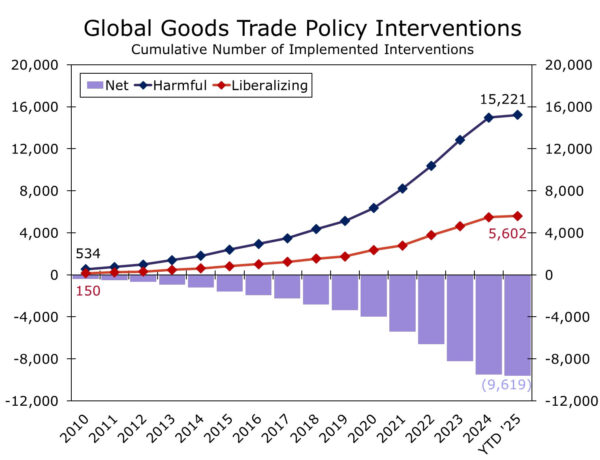

We have noted in multiple previous reports how the global economy is in a state of deglobalization. Meaning, the global economy is less interconnected today than it was 15 or so years ago. Reduced global inter-connectivity and a fragmenting global economy is arguably one of the most interesting long-term trends and seems to be a topic that is continuously unfolding. While the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-2009 (GFC) started the second era of deglobalization, the rise in trade protectionism around the world post-GFC exacerbated this deglobalization trend. The years immediately following the GFC saw a rise in protectionist trade policies; however, inward-looking trade policies picked up pace in 2016 with Brexit and the policies pursued by the first Trump administration. Protectionist trade policies gathered momentum over the course of Trump 1.0 and COVID, but also as a result of nearshoring and attempts to remove China from global supply chains, as well as military conflicts in Europe and the Middle East. According to Global Trade Alert, governments around the world responded to each of these developments by implementing more inward-looking and “harmful” trade policies (i.e., policies that reduce global trade cooperation) rather than policies that liberalize trade (i.e., more integrative global trade policies). In fact, over the past 15 years, harmful trade policy interventions have significantly outpaced interventions to liberalize trade. Since 2010, authorities around the world have imposed over 15,200 cumulative harmful trade restrictions as opposed to just over 5,600 cumulative policies designed to promote cross-border trade (Figure 1). Through the early months of 2025, data suggest that global trade policy is currently the most restrictive and protectionist it has been in the post-Global Financial Crisis era as harmful trade policies continue to be implemented at a more rapid pace relative to free trade types of policies.

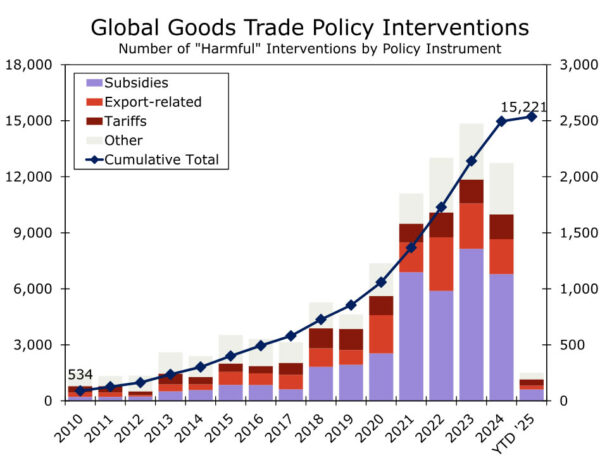

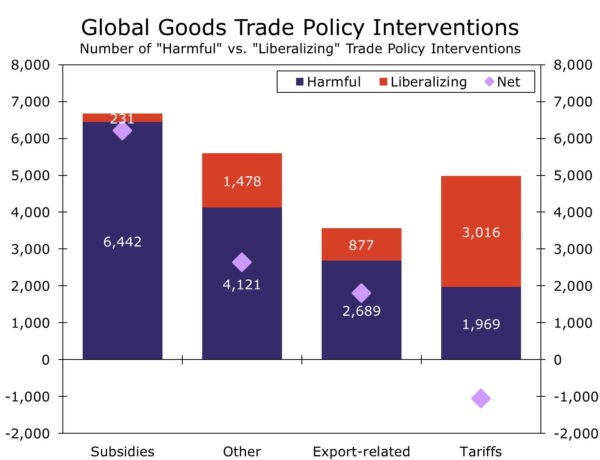

As far as the instruments used to implement more restrictive trade policies, tariffs typically come top of mind, especially when trade policy is discussed in the context of the Trump administration. And while tariffs have become a more widely used tool for protectionism, government subsidies, and to a lesser extent export restrictions, have been used more frequently to restrict trade cooperation, not tariffs (Figure 2). In fact, an argument exists that tariff policy changes, at a global level and on balance, have actually been supportive of global trade integration since the Global Financial Crisis. To that point, governments have offered more subsidies, while export restrictions and other trade policies—such as enhanced border inspections—have tightened. Tariff policy, as counterintuitive as this may sound, has been the exception. Over the past 15 years, governments around the world have opted to remove more tariff policies than impose new tariff restrictions. Global Trade Alert data indicate that governments have imposed ~2,000 tariff-related instruments that hurt global trade. At the same time, authorities have adjusted over 3,000 tariff policies to liberalize trade and promote closer trade ties (Figure 3). Which means, on a net basis, global tariff policy has eased since the GFC and evidence would suggest changes to tariff policy have been a re-globalization force.

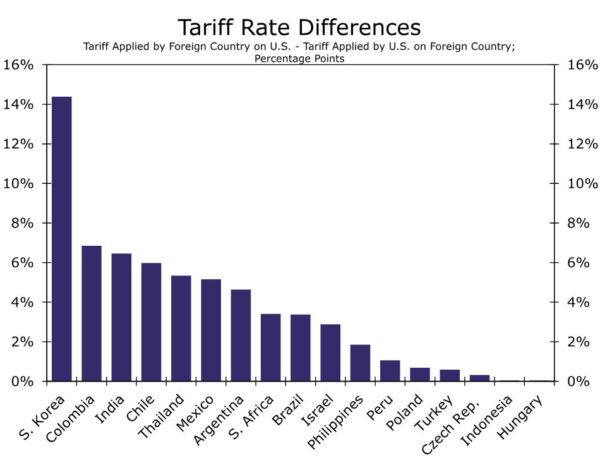

With that said, the Trump 2.0 administration has proposed very meaningful changes to U.S. trade and tariff policy, and not the kind of adjustments that would promote global trade cooperation. Trump has already implemented new tariffs, and rhetoric from the administration would suggest additional tariffs are forthcoming. Just this week, President Trump communicated a possible 25% tariff on goods from the European Union, reiterated his commitment to impose a 25% tariff on Canada and Mexico, and also raise the tariff rate imposed on China by an additional 10%. Trump has also communicated that reciprocal tariffs on select U.S. trading partners may be imposed in April, which would affect a wide range of countries across regions and countries not necessarily in the tariff bullseye during Trump’s first term (Figure 4). New tariffs on Canada, Mexico and China combined with reciprocal tariffs are a deglobalization force that will, by design, reduce trade connectivity. Taking Trump’s proposed tariffs a step further, retaliation from any country—or all countries—would also be considered policy interventions that would contribute to further trade fragmentation and deglobalization. In our view, China is likely to retaliate with matching tariffs similar to the reaction put in motion during the original trade war. Canada and Mexico have also tentatively signaled a willingness to impose retaliatory tariffs, and the EU would also likely respond with targeted or matching tariffs of their own. Over the past 15 years, tariff policy changes may have been a net positive for global trade integration, and while time will tell how the new trade war plays out, the trajectory of trade rhetoric suggests tariff policy will be a net negative for global trade cooperation.

We noted in the same prior reports how deglobalization is a negative development for global economic growth. In a scenario where global trade fragmentation fully materializes, the global economy could lose over 6% of overall output purely from diminished trade flows. The total hit to global growth would likely be more severe as the cross-border flow of investment and resources would compound the impact. But as the old saying goes, what happens in the real economy does not necessarily translate to what happens in financial markets. Real global economic growth should be disrupted from the imposition of U.S. tariffs and likely retaliation. To that point, we forecast below-trend global GDP growth of 2.7% as harmful trade policy interventions pick up pace. However, despite the contentious direction of global trade policy, we believe financial markets have become more comfortable digesting tariff headlines and future deglobalization-style trade policy changes. In our February International Economic Outlook, we expressed our view that market participants may be experiencing a degree of tariff fatigue. That is, despite trade policy uncertainty spiking, financial markets are worn out from being warned about tariffs. “Been there, done that,” financial markets might be saying, as gauges of volatility across FX, equities and rates continue to grind lower. Investors may also feel tariffs will be avoided, given Trump’s transactional approach to policy intervention and his search for the next “deal” that benefits America. We adjusted our long-term view on the U.S. dollar to reflect tariff fatigue, and while we still believe the dollar can strengthen against most foreign currencies, the peak is now likely to be lower as safe-haven support is somewhat removed. Time will tell on whether markets are indeed apathetic toward tariffs, or if investors are too complacent, but for now we believe market participants lean toward tariff apathy.