Part I: A New Toolkit to Predict Soft-Landings, Stagflation and Recessions

Summary

- In this first part of a series of reports, we introduce a new toolkit to predict the probability of soft-landing, stagflation and recessionary episodes.

- Bernanke (2024) reviewed the Bank of England’s forecasting process for monetary policymaking, concentrating on the Bank’s forecasting and decision-making during times of significant uncertainty. Bernanke outlined some recommendations to design effective policy decisions, placing emphasis on accurately identifying and quantifying risks to the outlook.

- We believe our proposed new framework would help decision makers effectively quantify potential risks to the economic outlook by moving away from the traditional approach of just forecasting recession probability and/or GDP growth rate predictions for the near future.

- The recent monetary policy path has been different from both the recession and the soft-landing projections of 2023, emphasizing the importance of not just concentrating on recession and soft-landing scenarios to forecast policy decisions.

- The toolkit helps analysts identify (a) whether the next phase is a soft-landing, (b) if stagflation is in the near-term picture and (c) whether a recession is coming.

- This report sets the stage by showing why the three economic outlook scenarios are important for monetary policy decisions, particularly in gauging the potential pace of the upcoming easing cycle.

- In the next installment of this series, we quantify historical episodes of soft-landings, stagflation and recessions.

Setting the Stage: A New Toolkit to Quantify Potential Risks to the Economic Outlook

Bernanke (2024) reviewed the Bank of England’s forecast process for monetary policymaking, concentrating on the Bank’s forecasting and decision-making during times of significant uncertainty, such as in the early years of the post-pandemic era.1 Central bankers around the globe, including in the U.S. and U.K., were challenged by higher inflation and volatile growth rates. For the most advanced economies, the post-pandemic era’s higher inflation and volatile growth was, to some extent, different from the post-Great Recession period of muted economic growth and lack of inflation. Naturally, the post-pandemic era requires some new tools to help decision-making. In his review, Bernanke outlined some recommendations to design effective policy decisions, placing emphasis on accurately identifying and quantifying risks to the outlook.

We propose a new framework that would help decision makers effectively quantify potential risks to the economic outlook by moving away from the traditional approach of just forecasting recession probability and/or GDP growth rate predictions for the near future. We suggest characterizing the growth outlook into three different regimes, each of which are structurally different and would require different policy stances. This approach helps decision makers identify (a) whether the next phase is a soft-landing, (b) if stagflation is in the near-term picture and (c) whether a recession is coming. Moreover, the framework would help analysts project when it would be appropriate to (1) expect contractionary policies to fight higher inflation (higher probabilities of stagflation), (2) foresee policy normalization (higher probabilities of soft-landing) or (3) look for the start of expansionary policies (typically during a recession).

We readily acknowledge that, in some ways, predicting the probability of recession may be similar to forecasting the GDP growth rate; however, recession and stagflation predictions help to identify some potential risks to policy decisions. Historically, fighting stagflation is more challenging and may require a different policy path than recessions. For example, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) reduced the fed funds rate in the last four recessions, but raised the fed funds rate to fight inflation in the 1980s stagflation/recessionary episode.

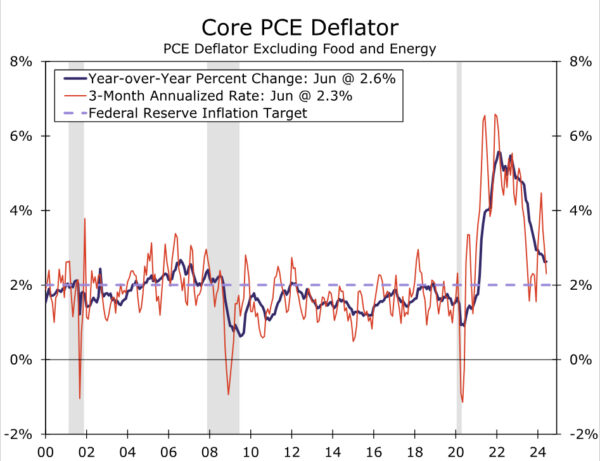

The current cycle stresses the importance of our proposed framework to generate the probabilities of the three suggested scenarios. For example, the past few years have noted talks of recession, stagflation and soft-landing. Members of the FOMC have been busy fighting higher inflation, volatile GDP growth rates and financial market participants’ worries about recession and stagflation. Initially, the FOMC characterized the inflation seen after the pandemic as “transitory.” When it turned out to be persistent, stagflation fears were raised, especially in the first half of 2022 which saw high inflation levels and negative GDP growth rates. To fight this decades-high inflation, the FOMC enacted the fastest rate hikes in decades. In response to the rapid rate hikes, analysts then predicted a recession. However, the U.S. economy proved resilient and has avoided a recession as of Q2–2024.

In summary, generating a forecast for the GDP growth rate and/or the probability of a recession during the next two quarters is not sufficient. For effective decision-making, it would be better to estimate the probabilities of each scenario (for example, a 30% chance of recession, 50% probability of soft-landing and 20% chance of stagflation). This would provide better information for decision makers who are setting policies for the future path of the economy.

Why is Predicting Recessions Not Enough?

During the 1990s, researchers started forecasting recession probabilities using logit/probit models.2 Recession probability forecasting has turned out to be useful as it helps decision makers by signaling recessions in advance. However, during the past three business cycles—each with the common theme of weaker recoveries—monetary policy stances were expansionary well after the official ending dates of recessions.

Most analysts rely on the NBER recession dates to build models that generate recession probabilities. The NBER employs several variables including GDP, employment and personal income to determine the start and end dates of a recession.3 Since most macroeconomic data are released with a time lag and are prone to revisions, the NBER announcements regarding a recession have start/end date lags. For example, on July 19, 2021, the NBER declared that the 2020 pandemic-era recession ended in April 2020. This announcement came over a year after the official recession end date.

However, monetary policy stances are typically set using near-term forecasts for the economy alongside historical data. That is, a recession forecast for the near-term would play a crucial role in policy decisions, all else equal. For example, most private sector forecasters were predicting a recession back in 2023, as shown in Table 1. Following the “technical recession” definition of two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth, in April 2023, 40 out of 58 forecasters called for a recession to start some time in 2023. In May 2023, forecasts for a recession peaked, with 74.2% of forecasters expecting a recession.

The private sector forecasters were also calling for an accommodative monetary policy stance similar to that which occurred during the past four recessions in which the Fed reduced the fed funds rate. In May 2023, the Blue Chip Financial survey expected the upper bound of the fed funds rate to peak in Q3–2023 at 5.25%, followed by a rate cut of 25 bps in December 2023. Furthermore, the Blue Chip consensus predicted four more rate cuts in 2024, with the fed funds rate ending at 4.00% by Q4–2024. In other words, a recession prediction was associated with an accommodative policy stance where the FOMC would start reducing the fed funds rate in December 2023.

Why Has the Recent Monetary Policy Path Been Different From the Soft-Landing Projections?

While private sector forecasters expected a recession, most members of the FOMC were predicting a soft-landing. In 2023, the June Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) had a median estimate of 1.0% in 2023 and 1.1% in 2024 for real GDP growth and 5.6% in 2023 and 4.6% in 2024 for the fed funds rate. It is important to note that in June 2023, the fed funds rate was 5.25% and the FOMC expected two more 25 bps rate hikes. This is consistent with a soft-landing prediction—the FOMC expected policy normalization to start sometime in 2024, as the fed funds rate was 100 bps lower (at 4.60%) than the suggested 2023 year-end rate of 5.60%.

Therefore, two different forecasts—recession vs. soft-landing—were predicting somewhat different paths for the fed funds rate. The private sector’s recession forecast was attached to an accommodative policy stance with rate cuts starting in 2023, while the FOMC’s soft-landing projections were suggesting more rate hikes in the second half of 2023 along with four 25 bps rate cuts in 2024 (according to the June 2023 SEP).

However, the realized path of the fed funds rates has been different from both the recession and soft-landing calls of 2023. The dual mandate of the FOMC is to foster maximum employment and price stability. However, as stated above, the NBER heavily relies on measures of output, employment and consumption to determine the start and end dates of a recession. Essentially, both the NBER’s approach and the theoretical definition of a soft-landing do not explicitly target inflation, even though inflation is part of the FOMC’s dual mandate.

Our recent work relies heavily on measures of inflation and output to characterize stagflation into mild, moderate and severe episodes, complimenting the NBER’s approach.4 It is important for our framework to capture major risks to the economic outlook in order to accurately predict policy stances.

The realized economic state turned out to be somewhat correlated with our framework of stagflation. Although FOMC members never explicitly acknowledged the risk of stagflation for the current cycle, their changing projections in the SEP are consistent with a stagflation risk. The June 2023 SEP projection of a soft-landing materialized into the actual economic state as of Q2–2024. However, the same SEP forecasted four rate cuts in 2024, and the FOMC has yet to cut this year. In fact, the most recent SEP in June 2024 suggested only one rate cut for the year.

The Upcoming Easing Cycle: Historians (Not History) May Repeat Themselves

In summary, recent years’ recession and soft-landing calls were unable to accurately predict the fed funds path, so we should not be looking for a traditional easing cycle. A rate cut at the September meeting is a more likely–than–not scenario, and analysts are gauging the potential duration and magnitude of the easing cycle. As evident in the current cycle, we think concentrating on one risk is short-sighted and that approach would be ineffective to accurately capture the path of the fed funds rate. Instead of expecting a repeat in the last four recessionary experiences in which the FOMC enacted rapid rate cuts, our proposal quantifies the economic outlook into the three scenarios to effectively capture potential risks to the economic outlook. The next report quantifies historical episodes of soft-landings, stagflation and recessions for the post-1950 period. Stay tuned!

Endnotes

1 – Bernanke, Ben. “Forecasting for Monetary Policy Making and Communication at the Bank of England: A Review.” Bank of England. April 12, 2024. (Return)

2 – Iqbal, Azhar and Nicole Cervi. “The Smoke Signal is Still Burning: Is Recession Coming?” Wells Fargo Economics. March 21, 2023. (Return)

3 – For more detail about the NBER recession dates, please see the NBER website. (Return).

4 – Iqbal, Azhar, Nicole Cervi and Delaney Conner. “Worst of Both Worlds: Are the Risks of Stagflation Elevated?” Wells Fargo Economics. April 17, 2024. (Return)