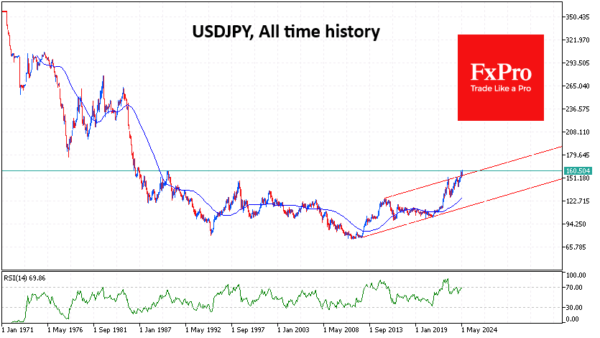

The Japanese yen has fallen to its lowest since 1986 against the dollar and a historic low against the euro. Its YTD loss is 12.5%, the third-worst performance after the Nigerian naira and the Egyptian pound among the 36 most liquid global currencies.

This performance of the currency has the monetary and financial authorities in the Land of the Rising Sun publicly displeased. However, their anger is not as strong as it was in October 2022 and November 2023, when powerful currency interventions reversed the trend from decline to growth for months. It was not even as strong as in late April when the USDJPY pair was pushed back more than 4% in five trading days.

The persistent pressure on the yen is the result of fundamental forces. Japan’s monetary policy remains ultrasoft, with the key rate at 0.1% versus the Fed’s 5.25-5.50%, justifying a long-term carry trade. The negativity on this topic is complemented by the disappointment of the portion of medium-term speculators who expected a more aggressive rate hike and winding down of the QE programme instead of one hike and discussion of reduced purchases.

Meanwhile, inflation is again showing signs of acceleration, although it is already near the target of 2% y/y, eating away at the value of yen savings.

We believe that the Japanese authorities’ hands are virtually tied, and they will continue to say more than they do for several reasons. The low key rate is holding down the cost of servicing the largest government debt relative to GDP. The abundant QE programme makes the Bank of Japan the largest buyer of bonds and also indirectly funds the government.

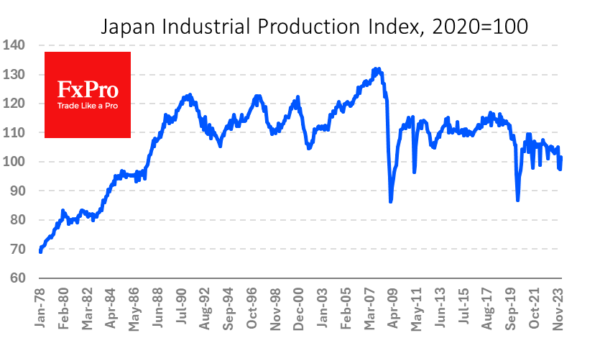

A sharp change in these parameters would be a blow to public finances. Accelerating economic growth and rising tax revenues should offset this negative. However, macroeconomic indicators are weakly improving: the balance of payments is back in surplus by a large margin, but the industrial production index is roughly where it was in the late 1980s, failing to feed into the 55% rise in USDJPY since early 2021.

In addition, currency intervention in support of the yen is burning up foreign exchange reserves, undermining the economy’s long-term sustainability.

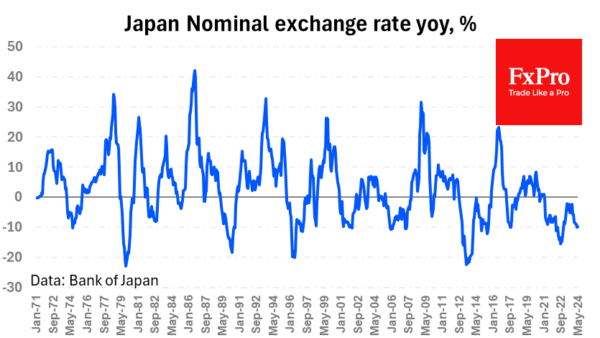

Without economic recovery, Japan is not interested in a yen reversal but only in easing volatility so as not to create currency shocks for businesses. At the end of May, the yen’s nominal effective exchange rate was 9.8% lower, which is within the norm, although not a reason for calm.

In our view, the Ministry of Finance and the Bank of Japan will continue to do the bare minimum necessary to contain the yen’s decline unless it suddenly experiences an economic boom that will force the economy to keep from overheating. In this regard, it should not be surprising that USDJPY will continue to move upwards, hitting 38-year highs, erasing the merits of the Plaza Accord.