U.S. Highlights

- January’s personal and income spending report landed just where it was expected to, with the only surprise coming from a bigger than expected lift from nominal personal income growth.

- The Fed’s preferred measure of inflation, core personal consumption expenditure prices, cooled to 2.8% year-on-year, with near-term trends suggesting it has room to fall.

- A weaker-than-expected ISM manufacturing report helped support the notion that demand is cooling.

Canadian Highlights

- If the Bank of Canada (BoC) needed another signal that its past rate hikes were working, it got it this week with the release of fourth quarter GDP.

- The economy returned to growth, but the pace remained in the doldrums for a country whose population grew by more than 3%.

- This below-trend pace of growth is exactly what the BoC wants to see for it to be convinced that inflation will continue to decelerate toward its 2% target.

U.S. – Coming Off the Boil?

January’s personal and income spending report landed just where it was expected to, with the only surprise coming from a bigger lift from nominal personal income growth. The as-expected print comes on the heels of updated GDP data that showed consumer spending closed out last year at an even better pace than originally thought. Most importantly, an upside inflation surprise was averted in January, allowing markets to let out a sigh of relief. After the data release Treasury yields tumbled and equities rallied. The data showed that price pressures continue to cool off. However, for a cautious Fed more progress will have to be made, leaving the first policy rate cuts a ways away.

First and foremost, this week’s personal income and spending report showed real personal consumption expenditures (PCE) pulled back 0.1% in January after healthy gains in November and December. Not a big surprise after January’s retail sales report showed a significant pullback. With some weather related factors weighing on demand it’s likely that this was more of a one-off than a new trend and February will likely show some bounce back.

Stronger-than- expected growth in personal income was largely a result of a larger cost of living adjustment in social security payments (and other government transfers), and the inflation adjusted real personal disposable income (PDI) measure showed no growth. Looking forward, this is what we’re interested in, as the downbeat month shaved two percentage points off of annual real PDI growth, bringing it down to 2.1% year-on-year. A deceleration in total real income growth is going to be part of the formula that cools the relentless consumer demand we’ve seen from the U.S. since the pandemic.

Of course, the Fed isn’t after just slowing the economy, but bringing demand and supply into better balance to tame inflation. On this front, yesterday’s report brought welcome news. The Fed’s preferred measure of inflation (core PCE) cooled to 2.8% year-on-year. Yes, still above the Fed’s target, but this is owing to base-effects from last year. Take a closer look at any near-term metrics and inflation is looking a lot closer to target. The three-month and six-month rates are at 2.6% and 2.5% (annualized), respectively. Smooth out some of the month-to-month noise in the series by taking a rolling quarterly rate of change, and core PCE prices have been advancing between 2% and 2.3% (annualized) since last September (Chart 1).

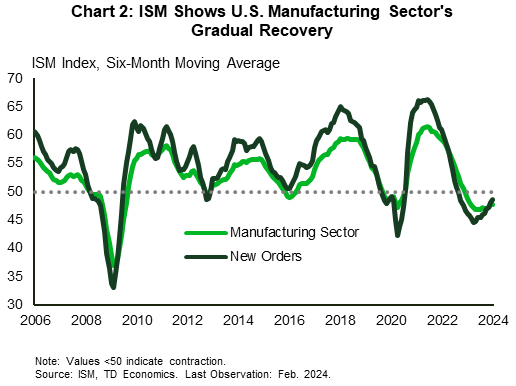

February’s ISM manufacturing report closed out the week, and supported the notion that demand is coming off a boil. With a 47.8 print for the month, the reading fell well short of market expectations and signaled that the recovery in the manufacturing sector is progressing rather slowly (Chart 2). Moreover, new manufacturing orders show that demand remains tepid.

For the Fed, these indicators come as signs that the relentless demand that powered the U.S. economy in late-2023 might be cooling off. Next Tuesday’s February ISM services report should shed light on the much larger services sector, while Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s testimony on Wednesday will hopefully give us a better sense of how the Fed is viewing these latest numbers.

Canada – Another Quarter of Weak Growth

If the Bank of Canada (BoC) needed another signal that its rate hikes were working, it got it this week. Fourth quarter GDP posted yet another quarter of sub-trend economic growth. That makes it three quarters in a row. Can it go for one more? Markets seem to think so, as firmer pricing around a June/July rate cut imply little hope for any forthcoming economic acceleration.

The details of the GDP report left little room for optimism. Yes, real GDP did increase by +1% quarter-on-quarter annualized (q/q) in the fourth quarter, after posting a negative print over the summer of 2023. And yes, this was above the BoC’s expectation for no growth. But, the pace of growth is still not much to write home about, coming in well below the trend pace for an economy that saw its population grow by +3% during the quarter.

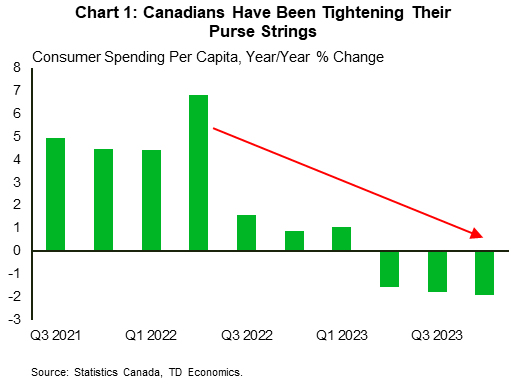

Consumer spending was tepid once again. If it wasn’t for the slow loosening of automotive supply chains, which has delayed the delivery of past car purchases, consumer spending would have shown effectively no growth over the last six months. Even worse, spending per capita contracted for the fifth time in the past six quarters, keeping the annual pace of growth firmly in the doldrums (Chart 1).

The only real positive in the report came from exports, which were by far, the biggest contributor to economic growth in the fourth quarter. Canada has benefitted from its trade linkages with the U.S., which has grown three times faster than Canada over 2023. Strong American demand for Canadian exports has provided a nice offset to our domestic economic slowdown. This could have some staying power as well. Energy exports have been in demand, and with new pipelines coming online soon, this new capacity appears to be arriving at just the right time.

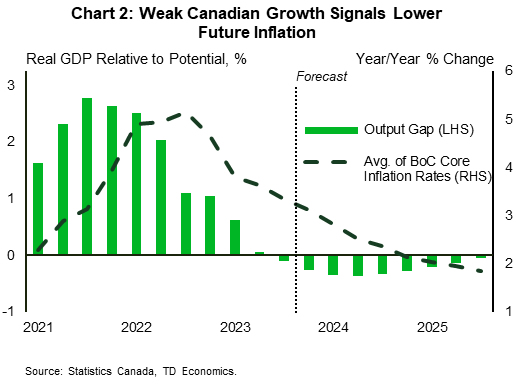

How does all this impact the BoC, which is set to make its next interest rate decision next week? The short answer is, not much. Outside of the one-off surge in spending in early 2023, Canadian economic growth has been abysmal ever since the BoC started raising rates in 2022. This period of below-trend growth is exactly what the BoC was hoping for. The central bank has been able to steer the economy from a state of excess demand – where consumer demand outpaced supply – to a state of greater balance. In economics jargon, the BoC has closed the output gap. Now, economic theory would tell you that when the output gap closes, and goes negative like it did six months ago, inflation will decelerate (Chart 2). From this lens, the wheels are in motion for inflation to move further towards the BoC’s 2% target. It is just a matter of time.

Luckily for the BoC, it has been gifted a little more time before it needs to cut rates. The fact that the economy has eked out modest, but still positive gains, means that a soft landing is still the base-case scenario. This allows the BoC to sit back over the next couple of months and ensure that inflation continues to grind lower. We think it will, which will allow the BoC to make its first rate cut in June.