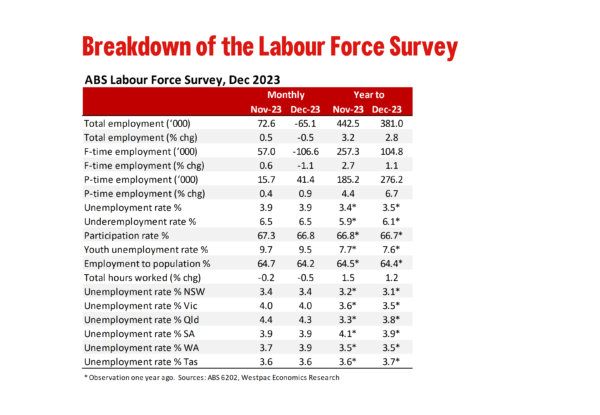

Employment: –65.1k (from +72.6k). Unemployment Rate: 3.9% (unchanged). Participation Rate: 66.8% (from 67.3%).

December’s labour force figures featured another surprise with regards to employment growth, this time to the downside, collapsing –65.1k (–0.5%) in the month. That compares to Westpac’s forecast of +35k and a softer market consensus of +15k. The number of people employed full time declined by -106.6k – largest monthly fall on record outside of the COVID-19 period. Part time employment partly offset this fall, increasing by 41.4k.

In their media release, the ABS noted that “The strength in employment in October and November and the fall in December, reflected changes in the timing of employment growth in the last few months of 2023, compared with earlier years.”

The ABS points to shifts in seasonal patterns as an important driver of recent results for employment. A possible explanation for this may be the growing importance of Black Friday Sales in Australia. This has likely meant that employers are hiring extra staff in October and November, instead of December.

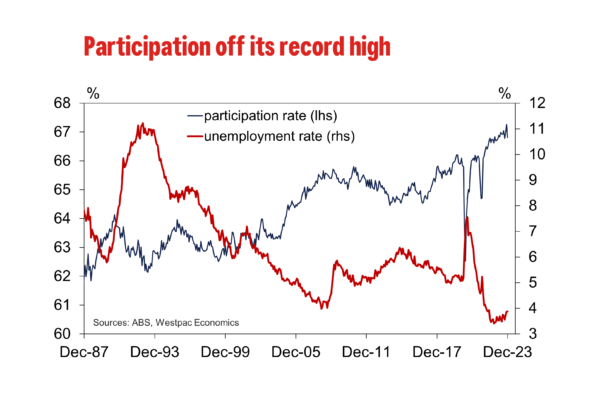

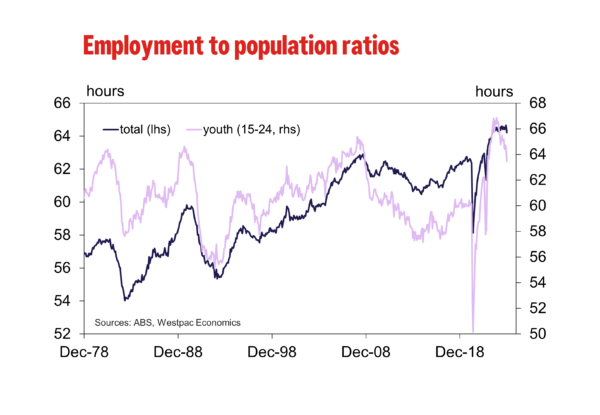

In line with the large fall in employment, the employment-to-population ratio also corrected, from an upwardly revised record high 64.7% in October to 64.2% in November, the lowest since May 2022. Similarly, the labour force participation rate moved sharply lower, from an upwardly revised record high of 67.3% in October to 66.8% in November to be broadly in line with the rate seen in September.

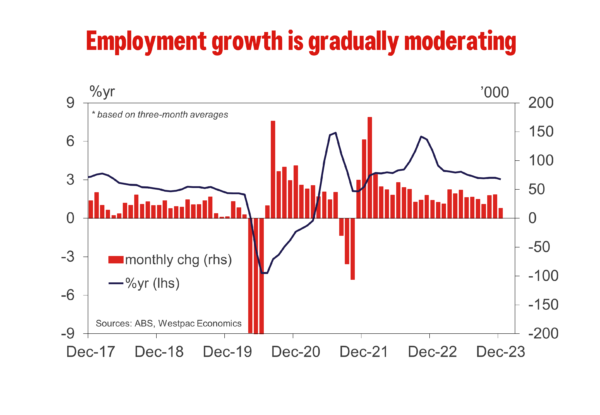

Looking through the monthly volatility though, employment growth has been tracking a monthly pace of 0.7% on a three-month rolling basis since September – lower than the pace of 0.9% recorded over the three months to June. This is consistent with a gradual slowing in employment growth and an unemployment rate that has begun to drift upwards into year-end.

The broader picture is of a labour market that is in transition, as softness begins to emerge after a period of historic tightness. Volatility aside, individuals are participating in the labour market at record rates amidst the trifecta of household income pressures – elevated inflation, sharply higher interest rates and an increasing tax burden.

Unemployment Rate

There was little-change to the number of unemployed persons (–0.8k) in November despite the decline in employment (–65.1k). This implied a contraction in the size of the labour force (–66.0k), reflecting that many individuals decided to “exit” the labour force in the month. That resulted in the unemployment rate holding flat at 3.9% in December.

While the unemployment rate has been clearly trending higher over the last six months, it remains very low versus history, speaking to a tight labour market that is gradually easing. So far in this cycle, increases in the unemployment rate were largely a consequence of labour demand not being able to absorb all of the increase in labour supply, as opposed to an increase in layoffs and job losses. We expect that to broadly remain the case, with employment growth slowing as labour demand and supply come back into balance, seeing the unemployment rate continue to drift upwards.

Hours Worked

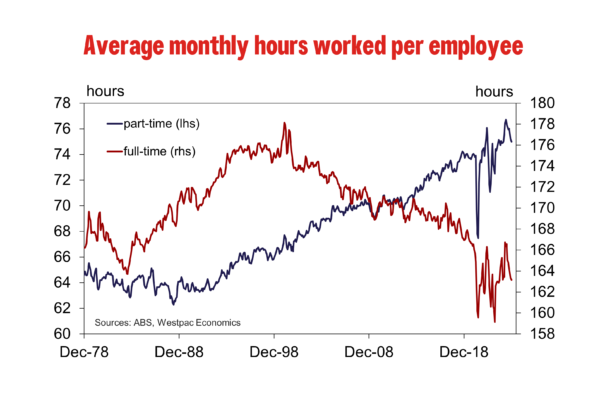

The number of hours worked declined by 0.5% over the month of December but was 1.2% higher than a year ago. There were particularly large monthly falls in Victoria (-0.9%), South Australia (-1.0%), and Tasmania (-0.8%).

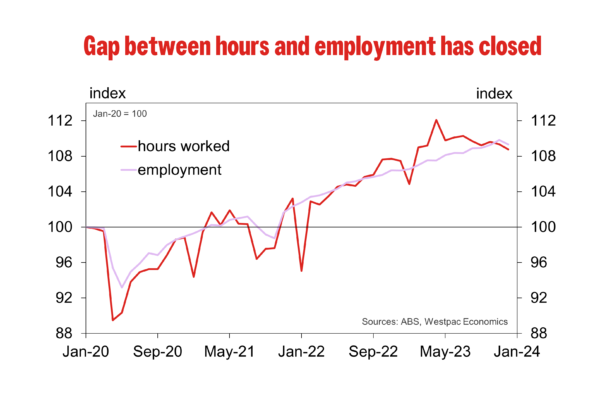

The number of hours worked rebounded strongly as the economy opened from COVID-19 induced lockdowns. Employers responded to strong demand and emerging skill shortages by squeezing as many hours as possible from their workforce. This saw the share of full-time employment (those working 35hrs/wk or more) increase to be around 70.3% in March 2023.

As demand softened and skill shortages eased, the share of full-time employment has trended down. In December 2023, it was 68.9%, around 1.2 percentage points lower than a year ago, and trending toward the pre pandemic average of around 68.5%.

This has seen growth in the number of people employed catch up to, and now exceed, growth in the number of hours worked. It has also meant that there has been a fall in average hours worked, which is consistent with the rise in underemployment as more Australians indicate that they would like to work more hours. Average hours worked per employee fell 0.5% in the month and 1.8% in annual terms.

As the supply side of the economy continues to adjust from the COVID-19 shock and demand slows on the back of tighter macroeconomic policy, employers are likely to pull back on demand for labour. Given how tight the labour market has been during this cycle, employers are understandably wary of letting people go. Instead, they are likely to make this adjustment through demanding fewer hours of their employees.

Other Labour Market Measures

The underemployment rate, which measures the share of employed workers who are willing and able to work more hours, held flat at 6.5% in December. Underemployment has been trending upwards since before the unemployment rate started to do so. It is currently in line with the rate observed in August, which was the highest rate of underemployment since February 2022.

The underutilisation rate, which combines the unemployment and underemployment rates, also remained, at 10.4%.

The youth unemployment rate, which measures the share of unemployed workers between the ages of 15 and 24, fell from 9.7% in November to 9.5% in December. That said, the employment-to-population ratio for this segment has corrected sharply over the course of the year, from 66.5% in January to 63.5% in December. Being a highly elastic group to changes in labour demand, this provides another signal that softness in labour demand is emerging.

Outlook

Labour market conditions have clearly softened. While shifting seasonality has blurred the signal from the seasonally adjusted data, the underlying trend is clear: demand is slowing, while potential labour supply continues to grow. We are seeing labour demand slow when it comes to growth in employment, but more clearly through the number of hours worked.

As labour demand slows and labour supply increases, we expect employers to continue to adjust the number of hours worked. This has been quite stark when it comes to the share of full-time employment, which has fallen by around 1.2 percentage points compared with a year ago.

The cooling underway in the labour market is expected to continue as we move into 2024. A key risk here is how quickly economic growth is likely to slow. At this stage, we expect the slowing in the economy to be gradual.

But downside risks to growth cannot be ruled out. To date, the labour market has been a safety blanket for households experiencing intense cost of living pressures – the strong labour market has meant unemployed members of households could pick up a job, or employed members could pick up a second job or additional hours. Without this safety blanket, households may be forced to tighten their belts even further.