China has long been the world’s growth engine, but that status is under threat as its economic recovery has hit a major stumbling block and the high-growth era seems to be well and truly over. Exports are falling, consumers aren’t spending much, bank lending is slowing and the crisis in the property sector only seems to be deepening. Can the Chinese government navigate its way out of this mess, which is partly its own doing, or is there more pain to come?

The post-financial crisis credit boom

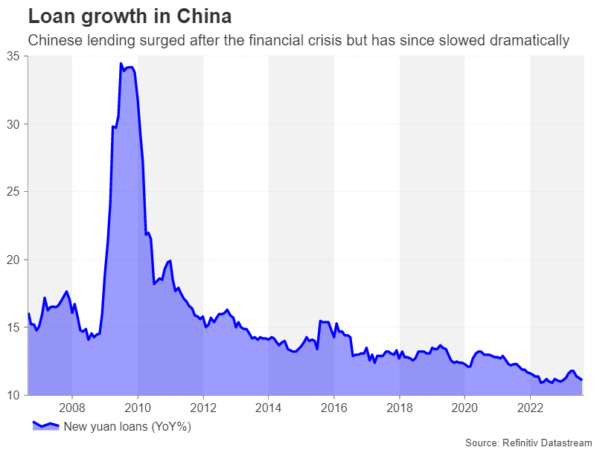

It could be said that China’s current troubles have been a long time coming. Whilst the slowdown became more pronounced after the pandemic, the root of the problem in fact goes back to the 2008 financial crisis. Just as other governments around the world resorted to extreme measures to boost their economies amid a global recession, Beijing came up with its own unorthodox policies to expand credit.

This inadvertently gave rise to the country’s infamous shadow banking sector, through which lending surged and set the stage for an unsustainable property bubble. To be fair to the government, it has made various efforts over the years to deleverage the highly indebted economy. But each attempt has brought about an unduly slowdown in growth accompanied by some form of market panic, forcing authorities to either backtrack some of their reforms or to find alternative backdoor channels for new stimulus.

Alarm bells are ringing in the property sector

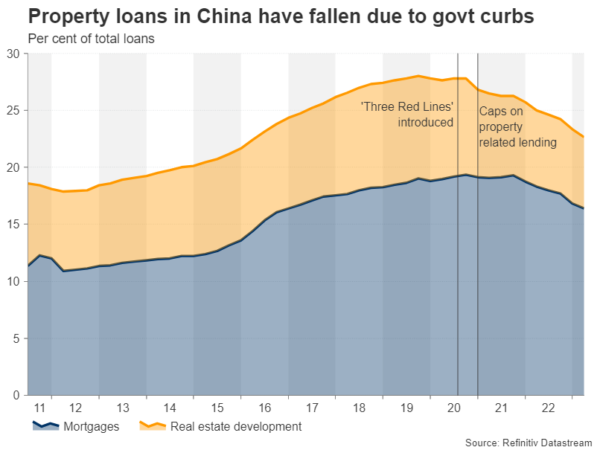

In many ways, the current crisis is no different, yet there are three distinctions that can be made this time round that ought to be raising alarm bells in Beijing. First, the property sector is facing collapse amid some high-profile defaults and many other big developers also drowning in debt.

The government recently eased borrowing restrictions for home buyers and announced more support for ailing developers. But the scandal of unfinished projects is so widespread that buyers have no confidence in the market and half-measures by authorities won’t be enough to prevent existing new homeowners from stopping their mortgage payments nor for potential homeowners to part with their cash. This makes it almost inevitable that more real estate developers will default in the coming months.

A worsening debt problem

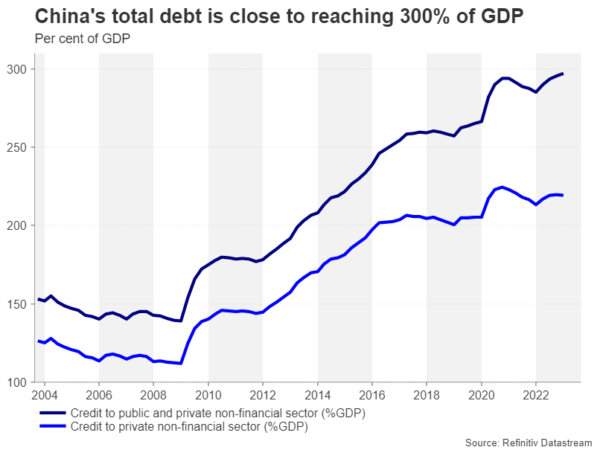

But what can the government do about it? Calls for a massive stimulus package keep getting louder but this would only risk fuelling more debt. Doing nothing is also not an option as shadow banks, many of which are state backed, are highly exposed to the property market. Should the real estate crisis spill over to the shadow banking sector, it could spark a broader liquidity crunch in the economy. There are already signs that some trust companies are struggling to meet the payments on their investment products due to liquidity problems.

And this takes us to the second distinction about why China’s latest economic woes are more severe than previous ones. China has one of the highest debt-to-GDP ratios in the world, running close to 300% when both public and private credit is combined. What this effectively means is that Beijing has limited scope to boost the economy through more lending, putting policymakers in a bind.

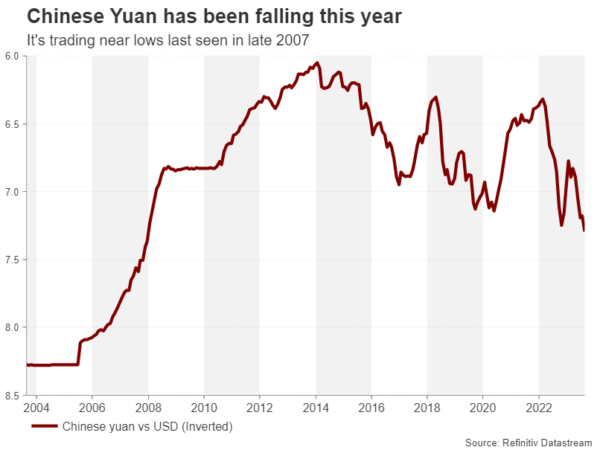

The fact that the government has been reluctant to bring out the big guns demonstrates its unease about adding to the soaring debt mountain. Policymakers’ dilemma has been made worse by speculative attacks on the yuan. The Chinese currency has depreciated by around 5.5% in the year-to-date on the back of the weakening economic outlook. This has tied the hands of the People’s Bank of China when it comes to how much it can cut interest rates at a time when slashing borrowing costs would be the appropriate policy response. The incremental cuts in interest rates have so far had a negligible effect in lifting sentiment, underscoring the need for bolder action.

Exports no longer a growth engine

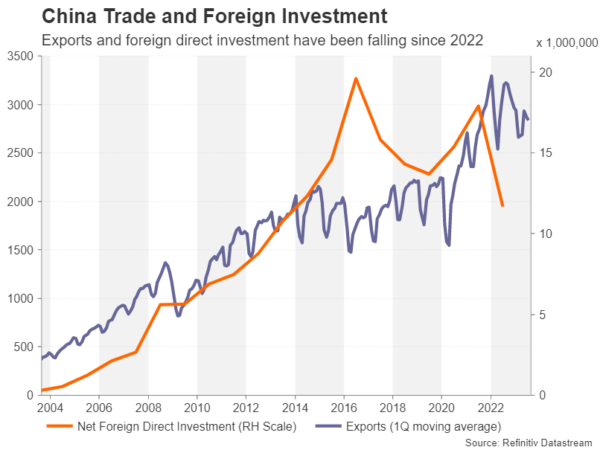

In a further blow for policymakers, exports – the backbone of the economy – have been quite sluggish over the past year and can no longer be relied upon to shore up growth in the hour of need. This brings us to the final point about why the risk of contagion, not just across the entire Chinese economy, but globally as well, is so high.

Although it’s true that rising interest rates in China’s main trading partners are dampening demand for Chinese manufactured goods, it’s not the only cause for the country’s deteriorating external balance. Exports have been on a downward trend since the beginning of 2022 and foreign direct investment last year was the lowest since 2013.

Trump’s trade war lives on

Trade restrictions imposed by the United States finally appear to be taking a toll on Chinese exports. But this isn’t the only setback. Other Western nations are also becoming increasingly wary about doing business with China, while Washington is additionally targeting investment in the country, specifically by US tech firms.

This can partly be explained as a legacy of Trump era policies, which the Biden administration has not only embraced, but also taken to the next level. But Beijing’s more aggressive foreign and domestic policies under Xi Jinping are also a factor as to why China has lost some of its business allure internationally.

The impact on China’s current account balance has been limited, as imports have also been falling during this period. Nonetheless, without substantial new inflow of foreign investment to generate more jobs and demand for exports dwindling, China is running out of options to kick-start growth.

The dreaded devaluation option

With the property mess and rising unemployment weighing on consumer sentiment, and businesses having the added headache of regulatory crackdowns, China is having a major confidence crisis right now and it could only be a matter of time before authorities realize that there may be just one way out of it.

China has yet to contemplate currency devaluation. Its attempts at stemming the yuan’s depreciation suggests this is not a preferred option. However, this has more to do with maintaining stability in financial markets and not being dictated by market forces than not wanting to use the exchange rate to stimulate growth.

The biggest obstacle to devaluating the yuan is the threat of drawing the ire of Washington. Still, if in a few months or even a year from now, the existing policy measures do little in lifting growth and external demand remains subdued, the government might feel justified to turn to its last resort.

A weaker yuan would immediately boost exports as well as free the central bank to pursue looser monetary policy. It wouldn’t solve the property crisis, but it could alleviate the problem by generating more jobs and lowering the debt burden on the economy.

Beijing unlikely to turn West

There is an alternative way of course of achieving all this and that is to mend ties with the West, particularly the US, and to open the domestic market to foreign companies. But such a shift is unlikely to happen anytime soon, if ever.

With the government determined to prevent a large-scale market fallout and at the same time wanting to avoid going down the road of bailouts and handouts, this approach of drip-feed stimulus may well end up being the worst-case scenario as it could lead China towards a Japan-style stagnation.

Could a Lehman-style collapse be a good thing?

However, if a major property developer or even a shadow bank were to collapse, whilst this would undoubtedly have huge ripple effects domestically and globally, it would at least necessitate the government to respond more forcefully, bringing about an economic turnaround sooner rather than later.

As things stand, there is little concern in US and European markets about a spillover from the turmoil in China’s real estate sector. The main worry is the prolonged drag on the global growth outlook.

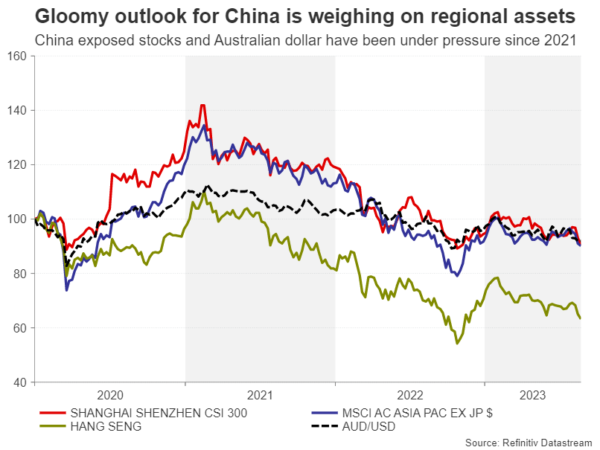

Aussie and Asian stocks feel the pain

However, for countries that are highly exposed to the Chinese economy such as Australia and New Zealand, their currencies have already been underperforming this year due to the ongoing uncertainties. The slowdown in China was likely a significant factor in the Reserve Bank of Australia’s earlier-than-anticipated pause in its tightening campaign.

The biggest impact, though, has been on regional stock markets. The MSCI AC Asia index (ex. Japan) has declined by over 30% since the 2021 peak when the reopening rally came to a halt. This is in line with falls of around 37% for China’s benchmark CSI 300 index. Worst hit has been Hong Kong’s Hang Seng index, which has plummeted by more than 40%.