Summary

China’s post-COVID rebound has now fully matured as the latest batch of activity data reinforced a slowdown is under way across the Chinese economy. As a result, we have revised our 2023 GDP forecast lower, and now believe China’s economy will grow 5.7% this year. Waning economic momentum has prompted easier monetary policy from the People’s Bank of China (PBoC), and we believe further easing is imminent as authorities are likely to lower bank Reserve Requirement Ratios in Q3-2023. Diverging paths for monetary policy between the Fed and PBoC have weighed on the renminbi, and while we are not adjusting our renminbi forecasts, we believe tactical opportunities exist to take advantage of potential renminbi underperformance.

Short-term growth prospects are now under pressure; however, China’s longer-term growth potential also faces robust challenges as structural issues persist and have arguably worsened. These structural hurdles stem from worsening demographic trends, an over-leveraged non-financial sector, and geopolitical developments that are more likely to suppress than enhance future economic growth prospects.

The Post-COVID Rebound In China Is Over

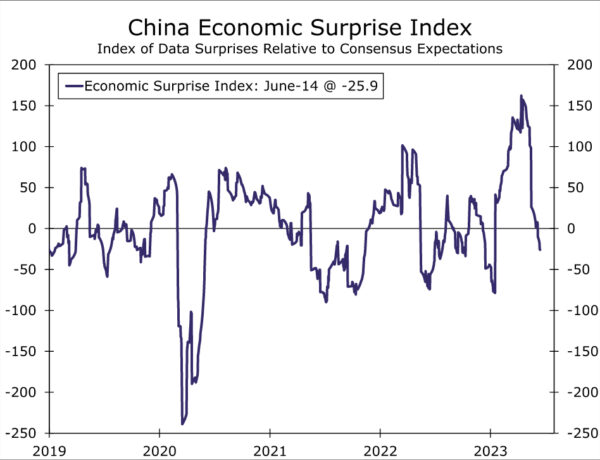

“Zero-COVID” protocols weighed on China’s economy for a good part of the past three years. COVID mutations and rising case burdens were met with harsh mobility restrictions that upended China’s economy, disruptions that trickled across Asia and other parts of the world. Eventually lifting COVID containment measures brought about an optimism that China’s economy would flourish. In fairness, the Chinese economy did outperform in Q1. China’s economy grew 2.2% quarter-over-quarter, a more robust pace of growth than we along with consensus forecast expected. However, the momentum from the first quarter has not been able to sustain itself and growth prospects for China’s economy are fading quickly. Currently, the May non-manufacturing PMI sits at 54.5, down from 58.2 in March, while the manufacturing PMI slipped deeper into contraction territory in May. Perhaps most concerning is that the April and May manufacturing and services PMIs fell more than consensus expected. In fact, underperforming sentiment as well as activity data have been a theme in China over the past few months. To that point, the economic surprise index—designed to measure whether data are outperforming or underperforming relative to expectations as well as the magnitude of performance—has declined rapidly since the end of March (Figure 1). Meaning, not only are data out of China suggesting the economy is slowing, but the deceleration is occurring at a quicker pace than initially expected. The latest batch of activity data for May, particularly retail sales, confirms China’s post-COVID economic rebound has fully matured. As a result, we are revising our GDP forecast lower, and now forecast China’s economy to grow 5.7% this year, down from 6% previously. Following this downward revision, risks around our forecast are now balanced.

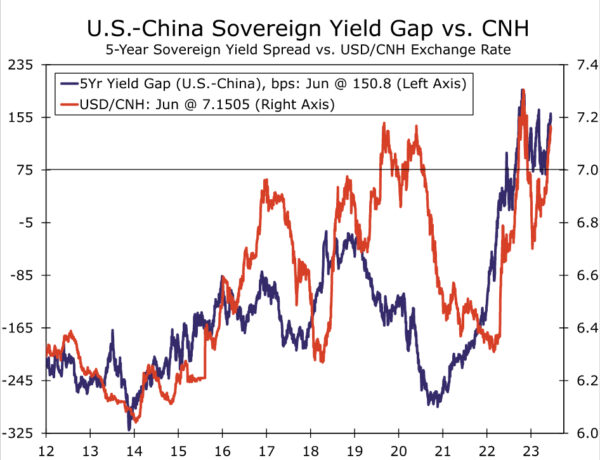

Recent actions and communications from Chinese authorities also suggest they are concerned with the overall health of the economy. Just recently, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) lowered short- and medium-term lending rates to encourage borrowing and support broader economic activity. Media reports also suggest authorities are considering deploying new fiscal stimulus, likely targeted at propping up the real estate sector, but also to possibly spark domestic consumption. While deploying fiscal stimulus is a possibility, we can say more confidently that we believe additional PBoC monetary easing will be the primary policy lever authorities use to support the economy and that further easing is likely forthcoming. In that sense, we believe PBoC policymakers will follow up their decision to cut lending rates with a decision to lower the Reserve Requirement Ratio (RRR) for local banks, and we reiterate our view that the major bank RRR will be lowered 25 bps to 10.50% in Q3-2023. Further easing will keep the PBoC and Federal Reserve on diverging paths for monetary policy, a dynamic that has historically applied depreciation pressure on the renminbi, and has resulted in a weaker Chinese currency more recently. While we baked widening interest rate differentials into our renminbi forecasts and forecast a weaker currency through Q2-2023, renminbi depreciation has been more pronounced than we expected to this point. However, the current sovereign yield spread between similar tenor Chinese government bonds and U.S. Treasuries suggests renminbi depreciation against the dollar may be topping out (Figure 2). While our forecast is for the renminbi to end Q2-2023 at 7.10, we opt to exercise caution and believe a renminbi recovery against the greenback is more likely to materialize than further depreciation based on medium-term yield differentials.

With that said, there are still tactical opportunities to position for renminbi underperformance. The RMB’s recent underperformance suggests a weakening linkage with the U.S. dollar and tighter linkage to the trade-weighted basket. With additional policy easing in China tilted toward monetary channels, we remain of the view that these are more likely to fuel outflows than change the broader narrative on economic growth. Real rates in China (1y FX forward implied rates less consensus inflation expectations) have continued to head lower against both developed and emerging market countries. Furthermore, we note that Chinese policymakers have not stepped in to stem FX weakness, suggesting a revealed preference for a weaker FX. In that sense, we like being short the CNH against currencies that are highly sensitive to a weakening trend in the RMB trade-weighted exchange rate (CFETS basket). The Wells Fargo Macro Strategy team recently recommended extending targets on long SGDCNH spot. Macro strategists will keep a close eye on the CNY’s fixing behavior, FX intervention activity and prospects for fiscal stimulus and/or broader credit easing for signs of a change in the currency’s weakening trend.

Future Growth Rates Are Not Promising Either

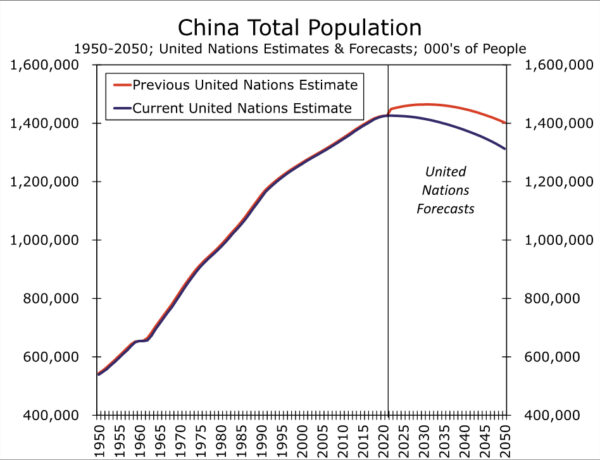

China’s economic slowdown is not just a short-term phenomenon, but a theme that should also play out over the longer term. We have commented on China’s structural challenges in the past and how these hurdles will place downward pressure on the Chinese economy’s long-term growth potential. Not only are these issues still present, but China’s structural challenges have worsened. To that point, China’s demographic profile has deteriorated in the past year. Slowing population growth has been a hurdle for some time; however, China’s population declined for the first time in decades at the end of last year. The outright population decline came 10 years earlier than the United Nations initially forecast (Figure 3), and with China’s working age population already shrinking, China’s potential growth is on a rapidly downward trajectory purely from a demographics perspective.

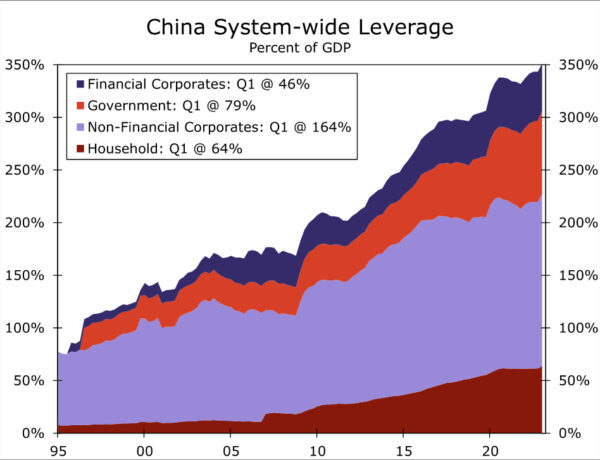

Compounding poor demographics is China’s debt problem, particularly leverage within the non-financial corporate sector. Since the 2008-2009 Global Financial Crisis, most of China’s growth has been driven by credit expansion. This credit growth has been directed toward the real estate industry and infrastructure spending has been critical to China’s growth story for the past 15 years. As a result, China’s non-financial corporate sector, mostly real estate firms, has amassed a debt burden worth 164% of GDP (Figure 4). This debt burden is more of a vulnerability; however, cracks in the real estate sector have formed over the past few years, most notably with the collapse of Evergrande and other large local property developers. State support has also been limited recently and “bail out’s” for over-leveraged firms have been rebuffed by Chinese authorities, leading to the possibility of a financial crisis unfolding in China. Two scenarios exist for China’s debt burden going forward, both of which are likely to result in suppressed potential growth rates. In the first scenario, the sovereign allows property developer defaults and bankruptcies, which can spill over to China’s banking sector and reduce confidence in the country’s financial system. Or, China actively tries to deleverage the economy, similar to efforts in 2015-2016. As mentioned, credit expansion has been key to China’s growth, should borrowing slow and leverage stabilize, future growth rates will be negatively affected.

And finally, geopolitical developments represent a structural issue that could weigh on China’s future growth rates over the long term. Supply chain diversification, tariffs, export restrictions, sanctions risk, and a somewhat elevated possibility of military conflict—intentional or accidental—in the Taiwan Strait could all individually and collectively have negative implications for China’s economy. As far as tariffs, Trump administration tariffs remain in place and are likely to remain in place going forward. Western allies have also imposed restrictions on intellectual property that can be exported to China, most notably microchips, in an effort to limit the nation’s technological advancements and steps toward a more digital economy. China’s coziness with Russia also keeps the risk of sanctions very much a possibility. And given China’s flurry of activity in the Taiwan Strait as well as commentary around reuniting the mainland and Taiwan at the 20th National Party Congress, the probability of military conflict in the South China Sea is higher relative to recent history. While we are not assuming any type of conflict, multiple flashpoints and event risks exist over the next few years that could lead to an escalation in geopolitical tensions between China, the United States and other economic powerhouses around the world. Next year, Taiwan will host presidential elections with pro-democracy and pro-sovereignty candidates seeing a fair amount of momentum early in the election cycle. China may look to disrupt next year’s election and could look to become more assertive in interrupting the democratic process in the United States around the time of the U.S. election in 2024. China also has stated its goal for technological independence by 2025—”Made in China 2025”—which could mean turning more aggressive toward Taiwan’s semi-conductor and technology capabilities. Also, the 21st National Party Congress will take place in 2027. In our view, one of President Xi’s potential motivations could be to cement his legacy within Chinese history. And securing that legacy could, hypothetically, even potentially mean unifying mainland China with Taiwan before the 21st National Party Congress meets in 2027. Point being, geopolitical risks involving China seem more likely to weigh on future growth than enhance growth prospects. While we will refrain from making any assumptions around geopolitical developments at this point, should any of these risks materialize, China’s economy would likely be negatively affected and place additional downward pressure on potential growth.