To Hike or Not to Hike, That Is the Question

Summary

- After raising rates by 500 bps since March 2022, the FOMC signaled at the conclusion of its previous meeting on May 3 that the tightening cycle may be coming to an end. That said, the Committee was careful to keep its options open regarding further tightening.

- Economic data that have been released after the previous FOMC meeting have generally been stronger than expected. In addition, financial conditions have been little changed since the May meeting. Consequently, some Committee members have indicated their preference to raise rates further on June 14.

- However, some key FOMC members, including Chair Powell, FOMC Vice Chair Williams and Governor Jefferson, seem content to leave policy unchanged at next week’s meeting to allow more time for past rate hikes to filter through to the economy.

- We see the most likely outcome for next week’s meeting as the FOMC making no change to its policy rate, but making clear that another hike at its July 26 meeting remains a distinct possibility. This combination would allow a compromise between officials who believe further tightening is necessary and those who believe it is time to be patient and let the medicine of the past year fully take hold.

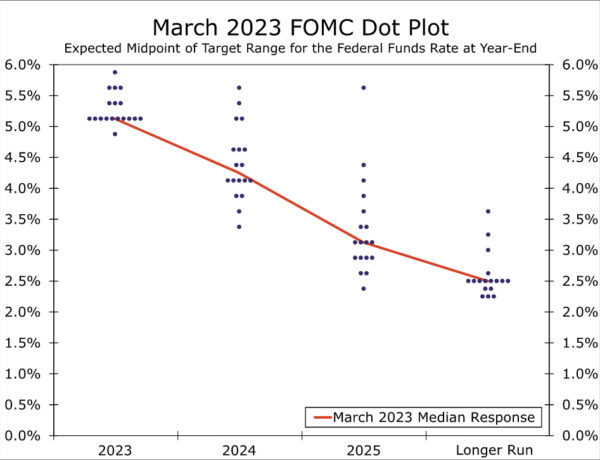

- The FOMC will release its quarterly Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) at the conclusion of its meeting on June 14. We think the median “dot” for year-end 2023 will shift up by 25 bps relative to the March SEP. If so, then most FOMC members would be indicating that the target range for the federal funds rate needs to go at least 25 bps higher from its current setting of 5.00%-5.25%. We think the median dots for 2024 and 2025 will also rise by 25 bps each to reflect a similar pace of eventual policy easing, as was the case in the March projections.

- We think most Committee members will bring down their forecasts of where they think the unemployment rate will end 2023, while nudging up their outlooks for GDP growth this year. We do not expect meaningful changes to the Committee’s inflation projections.

Take a Breath

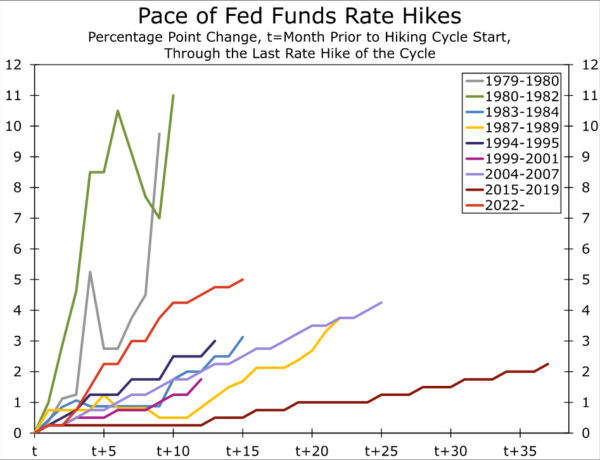

At the conclusion of the FOMC’s meeting on May 3, there were signs that the most aggressive tightening cycle since the 1980s was nearing its end (Figure 1). Policymakers voted unanimously to raise the fed funds rate by 25 bps to 5.00-5.25%, a 15-year-high. Yet, the Committee was careful to keep its options open about additional rate hikes. Rather than noting that it anticipated “ongoing increases” or even “some additional policy firming,” the post-meeting statement merely laid out the factors the FOMC would consider in determining how much additional tightening “may be appropriate” (emphasis ours). The change in language implied that Fed policy may have already arrived at a point where the FOMC could wait and see how the cumulative amount of tightening this cycle—a 500 bps increase in the fed funds rate and a $550B reduction in its balance sheet—is impacting the economy given the lagged effects of monetary policy.

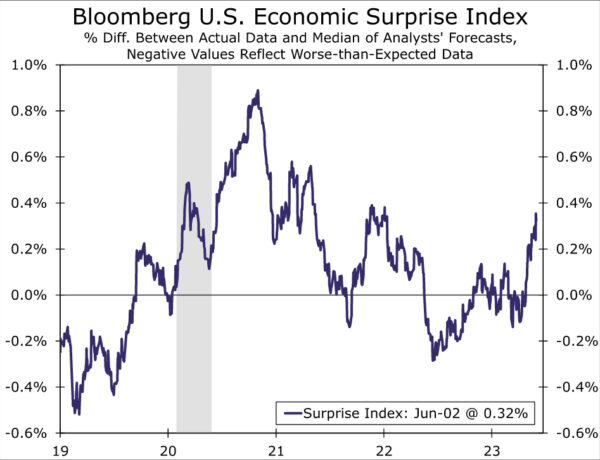

Because of these uncertain lags, the FOMC remains dependent on incoming data to guide its next steps. Since the FOMC’s most recent meeting, the economic data have come in stronger than expected, driving the Bloomberg U.S. Economic Surprise Index to a 17-month high (Figure 2). Consumers stepped up spending on both goods and services in April, putting real personal consumption expenditures on track to grow at a 1%-2% annualized rate in Q2. Business investment looks a little stronger as core capital goods orders in April rose by the most in more than a year, and spending on private nonresidential construction has increased more than 10% year to date. Meanwhile, the dearth of existing homes for sale is supporting a modest rebound in residential investment, with single-family permits increasing for three straight months and homebuilder confidence rebounding to a 10-month high.

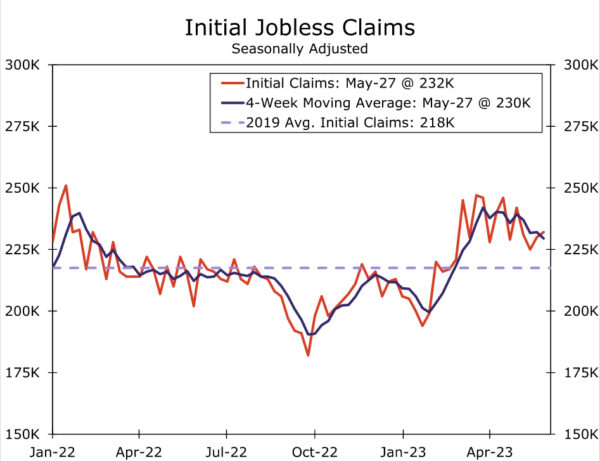

The labor market data have been equally strong. Nonfarm payrolls increased a robust 339K in May and have grown at an average pace of 283K over the past three months. Wage growth has cooled a bit but remains above what would be consistent with the Fed’s 2% inflation target. Layoffs have moved sideways in recent months whether measured by initial jobless claims, the JOLTS data or Challenger job cuts announcements (Figure 3). Supply and demand are coming into better balance in the labor market, but only gradually.

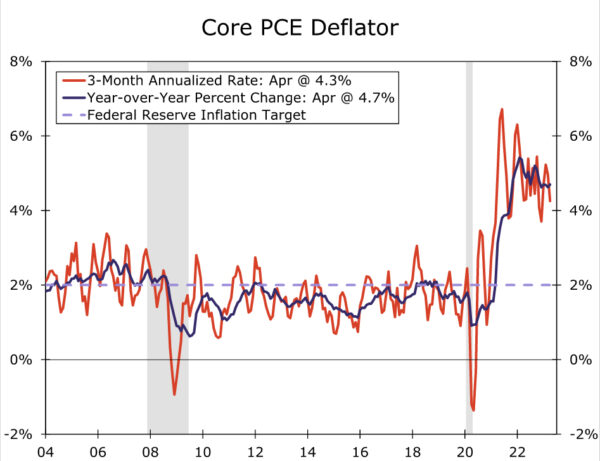

The corollary to resilient activity, however, is sticky inflation. The trend in inflation has yet to convincingly bend. The core Consumer Price Index has advanced 0.4% or more for five consecutive months, while April’s above-consensus increase in the core PCE deflator keeps the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge running two-times higher than the Committee’s target when measured on a three-month annualized or 12-month basis (Figure 4). The FOMC will get another important look at recent inflation trends with the May CPI report scheduled to be released on June 13, the day the FOMC kicks off its meeting. Tamer commodity prices should leave overall consumer prices in May little changed. However, the core CPI index is on track for a 0.3%-0.4% monthly rise by our estimates, furthering the notion that inflation remains stubbornly high.

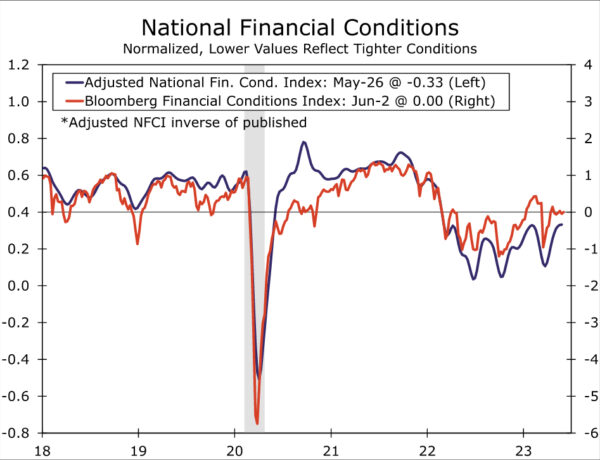

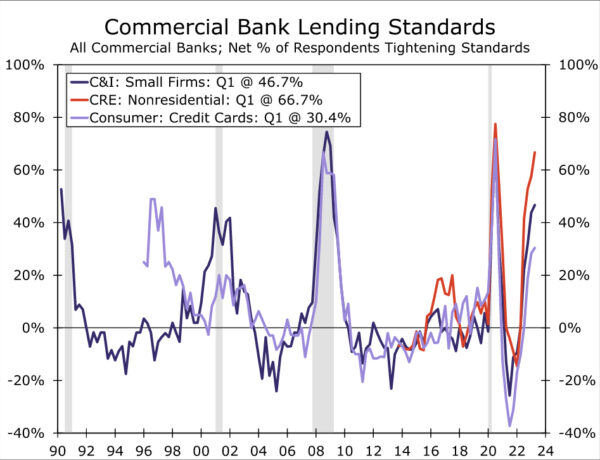

Meanwhile, financial conditions—the channel through which Fed policy affects the real economy—have been little changed since the FOMC’s May meeting and are easier than a year ago when the Fed’s tightening campaign was in its early months (Figure 5). The S&P 500 index has risen by nearly 12% since the last trading day of 2022, and corporate bond spreads are little changed on balance over the same period for both investment grade and high yield debt securities. Private lending conditions are more difficult to measure in real time and may be tightening more than public markets suggest. Unsurprisingly given the turmoil in the banking sector in March, credit standards at commercial banks tightened over the first quarter, though not materially more than the prior quarter (Figure 6). The KBW regional bank index has risen roughly 4% since the previous FOMC meeting on May 3, although it remains down significantly on the year.

The strength in the latest economic and financial market data has led to a meaningful number of Fed officials expressing their opinions that a bit more tightening likely will be needed to rein in inflation. Between data beats and a chorus of Fed officials sharing they are unconvinced monetary policy is significantly restrictive, the market-implied probability that the FOMC would hike another 25 bps at its June meeting rose to nearly 70% in late May.

Yet, key Fed officials, including Chair Powell, FOMC Vice Chair Williams and Board of Governors Vice Chair-nominee Jefferson, seem content to leave policy unchanged at the upcoming meeting to give more time for the past year’s policy changes to filter through to the economy. On May 19, Chair Powell noted that “having come this far, we can afford to look at the data and the evolving outlook to make careful assessments.” A day earlier, Governor Jefferson stressed the lags of monetary policy and that “a year is not a long enough period for demand to feel the full effect of higher interest rates.” In what seemed like a pointed rebuke to markets pricing in a June increase, Governor Jefferson said just a few days before the blackout period began that “skipping a rate hike at a coming meeting would allow the Committee to see more data before making decisions about the extent of additional policy firming.” The small amount of fiscal tightening in the recent debt ceiling bill may also provide wavering FOMC participants some comfort that fiscal policy is at least modestly pulling on the same side of the rope as monetary policy.

Therefore, we see the most likely outcome for next week’s meeting as the FOMC making no change to its policy rate but making clear that another hike at its July 26 meeting remains a distinct possibility. This would allow a compromise between officials who believe further tightening is necessary and those who believe it is time to be patient and let the medicine of the past year fully take hold. We think this balanced approach will be enough to stave off any dissenting votes, but the uncertain outlook and increasingly fractured views within the FOMC have increased the odds that one or more dissents could occur at one of the upcoming meetings.

The timing at which to first take a step back and leave more time to assess the effects of policy seems a bit odd to us given the surprising strength of recent data and leads us to wonder if some Committee members are weary about the effect of even higher rates on the banking system. However, a “skip” would hardly be unprecedented. In the most recent tightening cycle of 2015-2018, the FOMC never hiked rates at back-to-back meetings. Even in the 1994-95 cycle when the FOMC was raising rates in 50 bps or 75 bps increments, it did so at every other meeting.

If the Committee does decide to leave the fed funds rate unchanged, we would expect the statement to emphasize the significant amount of policy tightening undertaken in a little over a year. But to keep the door open to potentially more tightening, the statement would likely maintain the reference to possible additional policy firming being appropriate. The clearest indication that FOMC participants believe some further tightening is more-likely-than-not probably will come from the Summary of Economic Projections (SEP), to which we now turn.

SEP: Modestly Higher Dots, More Resilient Economy

The upcoming FOMC meeting will include an update to the Committee’s SEP, which summarizes the macroeconomic forecasts that each FOMC member provides on a quarterly basis. In the previous SEP released at the March FOMC meeting, the median projection for the federal funds rate at year-end 2023 was 5.125%, which is the midpoint of the current fed funds target range. However, the “dots” for year-end 2023 had a clear upward bias; seven projections were above 5.125%, while just one was below (Figure 7). As a result, it would not take much to nudge the 2023 median dot a little higher, and accordingly we look for the 2023 median dot to be 5.375% in the updated projections. This could serve as an olive branch to the more hawkish members of the Committee who are concerned that more monetary policy tightening is still warranted. We think the median 2024 and 2025 dots will also rise by 25 bps each to reflect a similar pace of eventual policy easing, as was the case in the March projections.

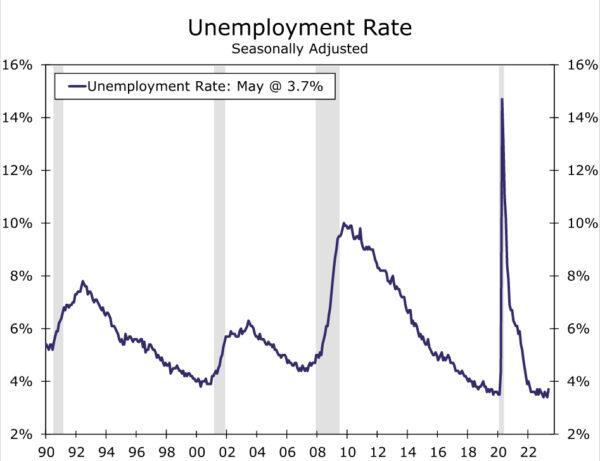

As we discussed earlier, the economy has outperformed expectations in recent months, and we believe the SEP will be updated to reflect this rosier near-term outlook. The current unemployment rate is a low 3.7% (Figure 8), but the March SEP included a median year-end projection for the unemployment rate of 4.5% in 2023. If realized, this would signal a rapid deterioration of the labor market in a short period of time. We think the Committee will revise its projections for this year’s unemployment rate down, with a median estimate of 4.1% or so plausible in our view. We doubt the 2024 or 2025 unemployment rate projections will change materially.

Similarly, the median projection for real GDP growth in 2023 looks too low at 0.4%. Real GDP growth registered a 1.3% annualized pace in Q1, and it appears to be on track to grow at least that fast in Q2. We think the median 2023 growth projection will rise by at least a few tenths of a percentage point, although the 2024 and 2025 projections may drift lower to reflect the lagged effect from past tightening.

Despite these changes, the Fed’s inflation projections probably will not change very much. The median core inflation projections might be nudged higher by a tenth of a percentage point or so, similar to the changes made in the March SEP. Headline PCE inflation could be revised lower by a similar amount given recent downward pressure on food and energy prices. On balance, however, we do not expect major changes to the Committee’s inflation projections.