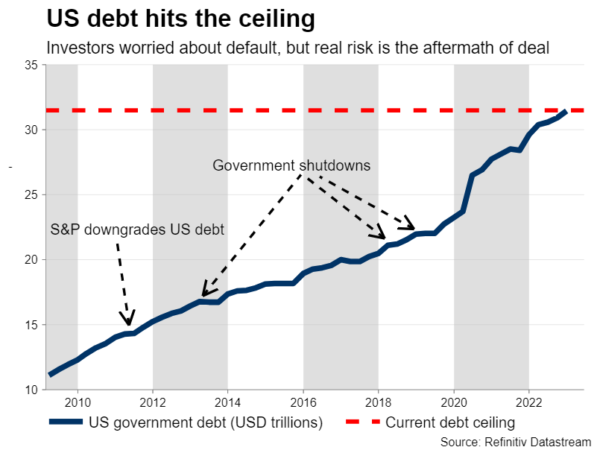

With US lawmakers unable to reach a deal on the debt ceiling, investors are laser-focused on the risk of a catastrophic default. However, the real problem for markets might be what happens after an agreement is found. That’s when the Treasury will scramble to raise its cash levels, which can drain liquidity out of the financial system and in the process, inflict damage on riskier assets such as stocks.

Political theater

It’s almost certain that US lawmakers will ultimately reach a debt ceiling deal, even if it takes some time. Nobody really wants the US government to default as that would severely damage the nation’s credibility, raise borrowing costs and make matters worse for both parties. This showdown is a political game of chicken, and investors are fully aware.

Republicans want the government to slash spending, whereas the Democrats are only prepared to freeze public spending at current levels. Some compromise will eventually be found, hopefully before the X-date that Treasury Secretary Yellen has warned is around early June.

In reality, there are some extraordinary measures the Treasury can take to avert default for a few more weeks, so the real X-date might be closer to late June. Even so, the real question is what will happen in the aftermath of the resolution.

Liquidity drain

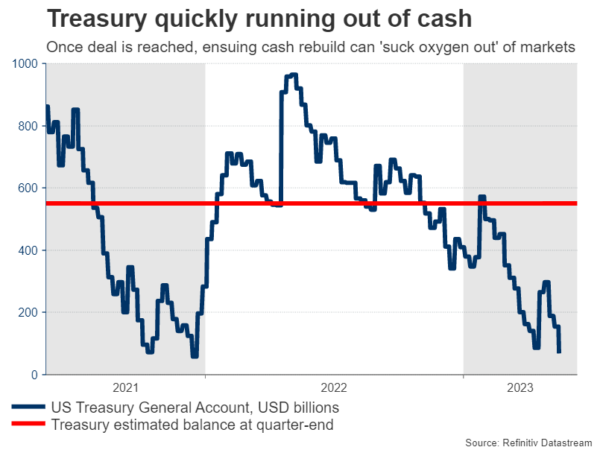

Once a deal is found, the Treasury would need to sharply boost its borrowing, in order to replenish its cash levels and be able to honor the spending obligations of the US government. This means a flood of newly-issued bonds will hit the markets in the following weeks, which investors need to absorb.

Let’s dig into the numbers. The government’s cash account at the Fed, called the Treasury General Account, currently stands at $60 billion. According to the Treasury’s own estimates, this cash balance is expected to soar to $550 billion at the end of this quarter and then rise to $600bn by the end of the third quarter.

This implies that around half a trillion dollars might be drained from the private sector, reducing bank reserves and in the process siphoning liquidity out of financial markets. Liquidity is the life blood of the financial system, so a sharp reduction would spell bad news for riskier assets such as stocks and cryptocurrencies.

And that’s without even considering the Fed’s quantitative tightening (QT) program, which is reducing its balance sheet at a steady pace. Hence, it looks like the Fed and the Treasury will be simultaneously pulling liquidity out of US markets this summer, effectively ‘sucking the oxygen’ out of the room.

QT kicks into overdrive

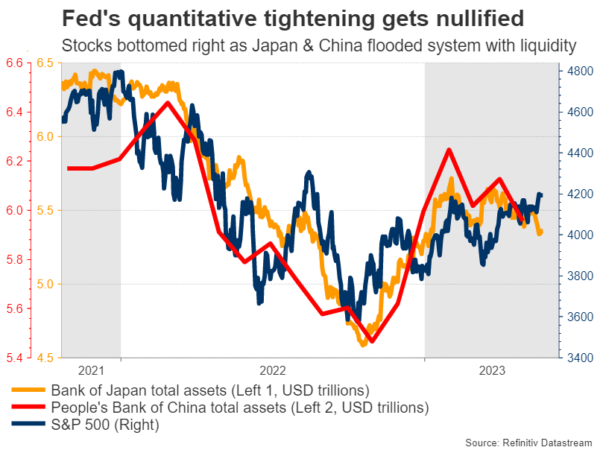

Markets have essentially taken a break from quantitative tightening since last October. Since then, the Fed has shrunk its balance sheet by only $300bn, but the Bank of Japan and the People’s Bank of China have jointly injected around $1.2 trillion into their own financial systems.

Liquidity is a global phenomenon, so the tremendous expansions in China and Japan have more than eclipsed the Fed’s cautious efforts to remove liquidity. It is probably not a coincidence that stock markets bottomed in early October, exactly when these foreign liquidity injections started.

But this liquidity effect seems to be going into reverse now. The balance sheets of the Japanese and Chinese central banks have been falling in recent weeks, the Fed is still reducing its own, and the Treasury is about to turbocharge this process.

Market effects

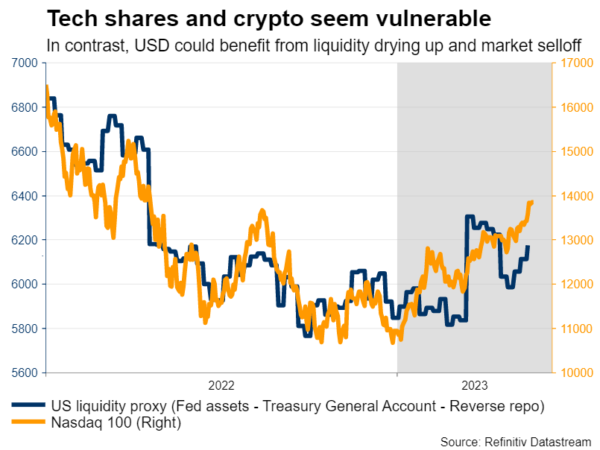

Blending everything together, investors are staring down the barrel of a dramatic liquidity extraction in the coming months, just as the real economy starts to feel the lagged impact of all the previous rate increases.

This is important because it could mark the end of the stunning rally in risk assets. Long duration plays such as tech stocks or shares of speculative profitless companies would likely get hit the hardest, alongside cryptocurrencies. The riskier the investment, the more vulnerable it is in an environment of evaporating liquidity.

With the tech-heavy Nasdaq 100 index rising by nearly 27% so far this year and Bitcoin rallying 64% over the same timeframe, these instruments already seem overextended and susceptible to a deep correction. In contrast, the main beneficiary in the FX arena might be the US dollar, which tends to perform well when liquidity dries up and markets sell off.

In conclusion, investors seem to be focusing on the wrong risk. Even if the US government shuts down next month, the politicians will eventually strike a deal. What’s most important is what happens afterwards once the Treasury unleashes a tsunami of bond issuance, amplifying the effects of quantitative tightening.

It could be a tough summer for riskier investments, which have been flying high this year.