When the Fed started signalling higher for longer last summer, everybody assumed that the first thing to break would be consumption, followed by big job losses. Few anticipated that the banking sector would get caught up in the crossfire of the Federal Reserve’s battle against high inflation. After all, banks traditionally perform better in higher interest rate environments as their profit margins improve. So why is it that we are now talking about bank runs, in an eerie reminder of the days of the 2008 Financial Crisis, and what are the risks of this panic escalating?

SVB: the first domino to fall

It all started with Silicon Valley Bank – a mid-sized Californian bank that mostly lent to venture-backed tech and life science companies. The bank was well capitalized to begin with but found itself unable to meet clients’ requests to withdraw deposits as tech startups began struggling for cash under the weight of rising borrowing costs. Subsequently, SVB resorted to selling its assets to raise funds, most of which were locked in 10-year Treasury notes.

However, the timing to sell bonds couldn’t have been worse for SVB as sovereign bond prices globally have been hammered over the past year as their yields have soared on rate hike expectations. This meant that in its bid to find more cash, the bank incurred heavy losses when it was forced to sell its bond holdings at a lower price than what it purchased them for.

It can be argued that this business model was unique to SVB and it’s unlikely that other regional banks would face similar risks. But the problem is, if liquidity has started to dry up for SVB’s customers, it’s likely that other small-to-medium-sized businesses across America are having to tap into their cash deposits to stay afloat.

Are authorities doing enough?

More importantly, once there is a loss of confidence in the banking sector, it is hard to stem the outflow of cash from worried depositors. That is why US banks are far from being out of the woods and is also the reason the government is bowing to pressure to provide additional safeguards. US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has signalled that the deposit guarantees agreed for SVB’s depositors were not a one-off and depositors of other banks would be protected too if there is further contagion.

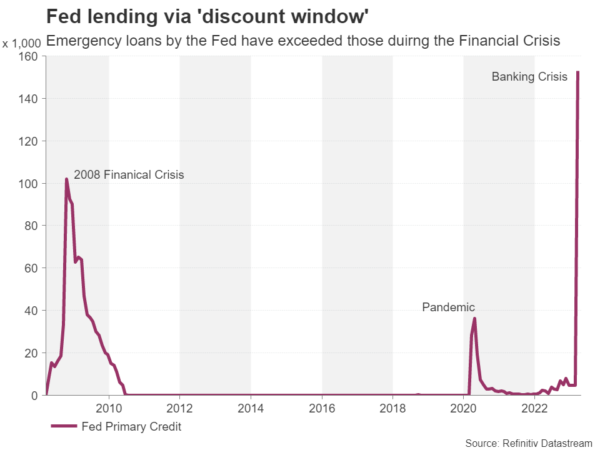

The Fed on its part launched a new emergency lending facility – the Bank Term Funding Program – and boosted dollar liquidity in the markets by increasing the frequency of its swap lines from weekly to daily operations.

Criticism about preferential treatment

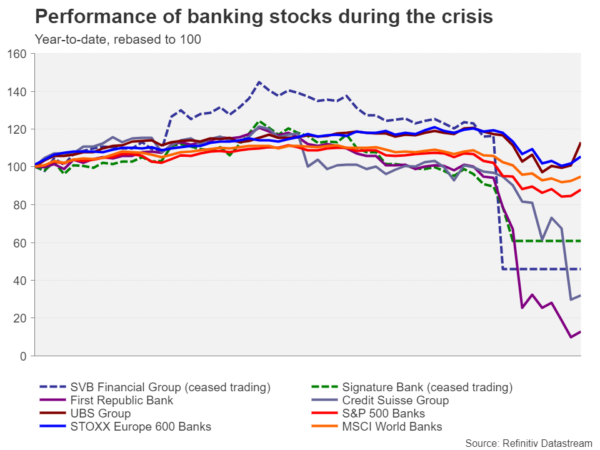

Unfortunately, the combined responses came too late for Signature Bank, whose collapse was also sparked by a run on deposits, most of which were uninsured, just like SVB. Although, there have been suggestions that the decision to shut it down was political due to the bank’s connections to the crypto industry.

Then there is First Republic Bank – another one with high uninsured deposits that had to be rescued with a $30 billion injection by 11 big Wall Street banks. The fact that First Republic caters to a lot of wealthy clients might have played a role as to why there was so much interest to save the bank.

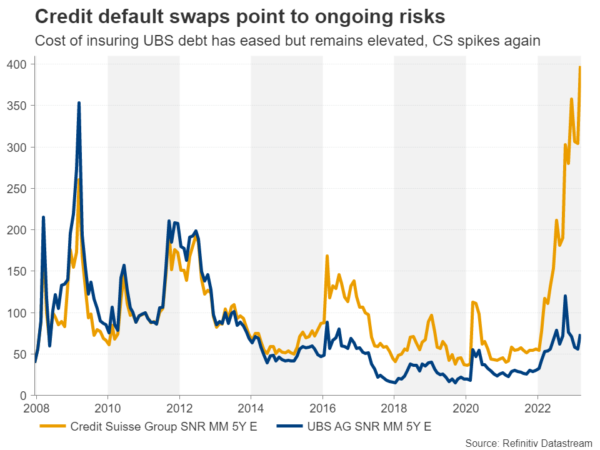

Other regional banks have suffered some degree of deposit runs too, but the outflow appears to be easing – something reflected in the rebound in their share prices. Even Swiss banking giant UBS’ stock is rebounding from the crash that followed after regulators and the Swiss government forced it to absorb its embattled smaller rival Credit Suisse.

Credit Suisse’s demise was a long time coming

It may be one of the oldest banks in the world, but Credit Suisse’s troubles predate this latest banking crisis. Its share price has in effect been in freefall over the past year, as the bank has been unable to draw a line over a series of scandals and mismanagement that have resulted in billions in fines from regulators around the world over the years.

However, Swiss authorities are hoping that this ‘shotgun wedding’ between UBS and Credit Suisse will put an end to all the speculation, especially as the total size of the rescue deal is worth more than the value of Switzerland’s GDP in 2022.

Is the fallout contained or still contagious?

So does this mean that the crisis is fading, or are all the measures that regulators and policymakers have come up with so far merely sticking plasters? It may be too early to tell, but several financial stress indicators are pointing to an easing in investor panic.

For traders, the bigger question is how does this episode affect the outlook for interest rates and therefore the outlook for the major currencies and the various asset classes, in particular, commodities and equities.

Systemic risk is greater in the US

In the euro area, President Lagarde has made it clear the European Central Bank will focus on getting inflation down by raising interest rates and use other tools to help banks with liquidity should they need it. However, in the United States, the situation is quite different. Although the Fed is not about to relinquish its responsibilities on price stability, there is a real risk of the banking problems becoming systemic due to the nature of America’s regional banks.

But even if policymakers decide not to press on with further rate hikes and regulators take their time to bolster banking rules, there is a growing concern and an expectation that banks in the US will toughen their lending standards on their own accord and take less risk until this crisis has fully blown over. This would lead to a significant tightening of financial conditions, which would have a similar effect to rate increases by the Fed.

A recession has become more inevitable

More to the point, a US recession is now looking more likely than before this turmoil began and the Fed going on pause earlier than anticipated may not necessarily prevent one.

That cannot be good news for the US dollar, which has already taken a battering on dimming rate hike bets and worries about the economy. Fresh jitters about the US as well as the global economic outlook have also knocked demand-sensitive commodities such as crude oil. Gold on the other hand has received a major boost, both on safe-haven flows and on the back of the plunge in bond yields.

For Wall Street, however, there isn’t a straightforward relationship with falling Treasury yields and a shallower Fed rate path, as the benefits of lower short- and long-term borrowing costs would have to be weighed against the impact a potentially weaker economy would have on corporate earnings.

But perhaps the worst outcome for the markets is if this crisis of confidence in the banking system drags on for several months without completely evaporating, toppling more banks along the way, until decisive action is taken by politicians, regulators and central banks.