Fed Preview: What It Takes for the Fed to Cut Rates

- The Fed looks keen on raising Fed funds rate to 5%. We expect a 25bp rate hike next week followed by another 25bp hike in March and May, respectively.

- A turn in the business cycle and drop in short-term inflation expectations pave the way for rate cuts next year, but the neutral rate is higher than before the crisis.

- We think the trajectory for Fed funds discounted by markets looks broadly fair, but we see slight upside to the front end of the curve and in particular 6M-2Y.

The Fed appears adamant to raise Fed funds rate to 5%, but it will take a little longer than we previously expected. We now look for the Fed to hike 25bp next week followed by two more 25bp hikes in March and May to conclude the hiking cycle. For markets, focus has already turned to looming cuts – the swap market discounts first two 25bp rate cuts already in the second half of this year. We look at what it takes this time for the Fed to cut rates.

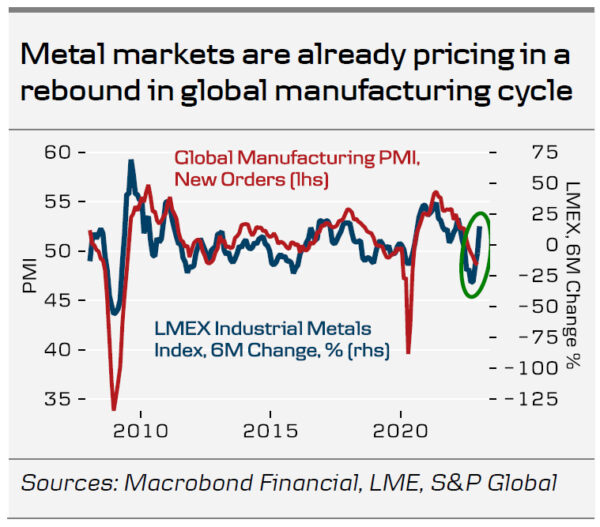

Normally, a turn in the business cycle paves the way for the Fed to cut rates. This time it needs to take into account the risk of prolonging the underlying inflation. The drop in inflation and wage growth are encouraging signs for the Fed, but labour market conditions remain tight. Recent easing in financial conditions and higher metal prices point towards a rebound in the manufacturing cycle, but the Fed cannot risk retightening labour markets too early when no real slack has been created. For now, most leading indicators remain firmly at recessionary levels, and we expect modest GDP contraction in the coming quarters, but the downturn could be shallower than previously thought. Some further easing in labour market conditions will still be needed for the rate cuts to materialise.

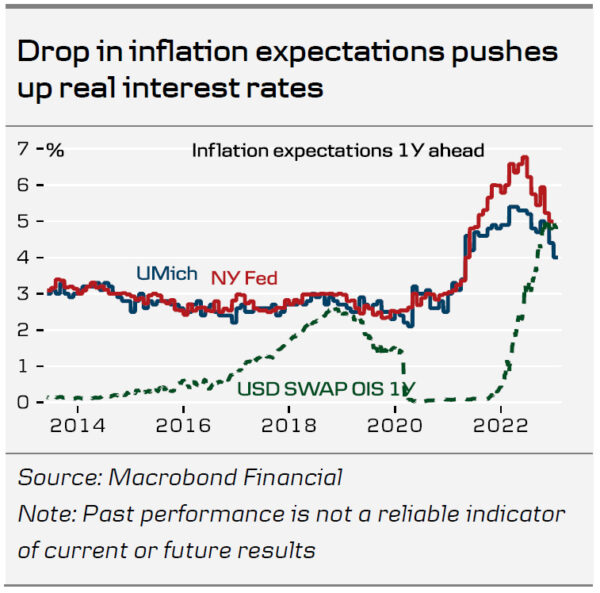

That said, the Fed could succeed in a soft landing, i.e. get inflation down to 2% and avoid a (deep) recession in the economy, which in our view would warrant rate cuts. A 5% policy rate is suitable, when inflation and inflation expectations are high, but not compatible with 2% inflation. Both market and consumer survey based short-term inflation expectations have declined recently, which means the Fed can lower its (nominal) policy rate and keep the real interest rate and thus monetary policy unchanged. The trend in short-term inflation expectations sets the pace and timing for the rate cuts even without a recession.

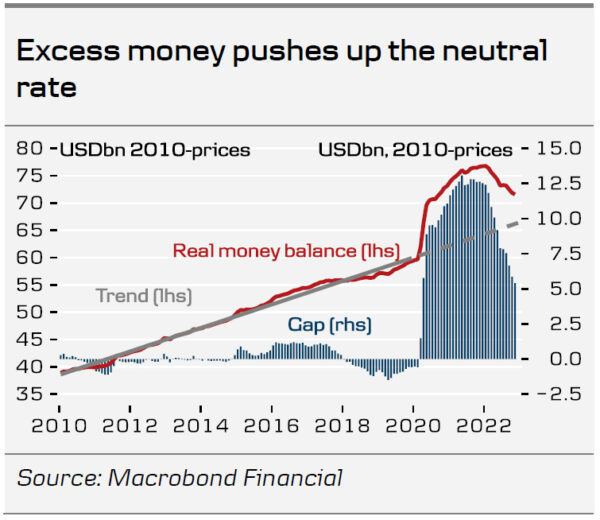

The neutral rate of interest in the US is higher now than before the crisis. There is still a real money balance surplus in the US. It requires the Fed to keep real interest rates higher to avoid a resurgence in inflation. If the neutral Fed funds rate was 2-2.5% before the crisis, it might now be 2.5-3%. It dictates the end-point for future rate cuts.

The market discounts the Fed to hike Fed funds to 4.9% in June and lower it to 2.5% in the coming 2-3 years. We think the trajectory looks broadly fair, but see upside to the front end of the curve and in particular 6M-2Y, i.e. we expect rates to peak at slightly higher level, for the Fed to first cut rates in 2024 and probably not all the way to 2.5%. This is a soft landing scenario for interest rates, where the US gets away with mild recession or avoids it completely. If inflation starts to rebound (e.g. on the back of the recent rally in commodity prices), the Fed may have to keep Fed funds at 5% or higher for longer. If labour market conditions suddenly deteriorate and inflation plunges, rate cuts would come sooner.