The Reserve Bank has released its November Statement on Monetary Policy (SoMP).

The highlight of these Statements is the Bank’s revised forecasts for growth, unemployment and inflation.

These forecasts are based on a path for the cash rate broadly in line with expectations derived from surveys of professional economists and financial market pricing (most likely a straight arithmetic average). Exchange rates and oil prices are also assumed to be unchanged through the forecast period.

This approach to cash rate assumptions can lead to some tensions. The forecasts are based on what the market and analysts expect for the policy instrument rather than what the Bank expects it needs to do. The risk with such an approach is that the Bank’s forecasts are consistent with market pricing but may not be consistent with the Bank’s own objectives. There is some evidence of this conundrum in the revised inflation outlook.

Forecasts are provided out to December 2024.

Due to the surprise lift in inflation in the September quarter inflation report, the Bank has raised its forecast for headline inflation in 2022 from 7.8% in the August SoMP to 8%. The forecast for inflation in 2023 has been lifted from 4.3% to 4.7% while 2024 has been lifted from 3% to 3.2%.

That means that the Bank is now forecasting inflation in 2023 to be much nearer 5% than the 4% we saw in August while it is clearly making the statement that it expects inflation will remain outside the 2-3% target range for three years. It is very rare for the RBA’s ‘out year’ inflation forecast to be above its target range – the only other instances being when major tax changes were set to boost the CPI (the carbon tax in 2011 and the GST in 2000).

Psychologically, a ‘near 5%’ forecast rise for 2023 may lift expectations for both business and households, particularly with wage negotiations that are currently taking place. Negotiations may also be influenced by further progress in the proposed changes, which the government is now close to legislating, that would allow for industry-wide bargaining.

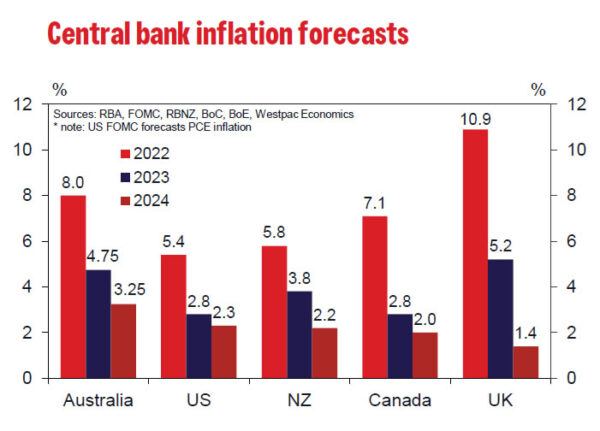

It is worth comparing the RBA’s forecasts with those of its central bank peers. The 4.7% for 2023 is well above the RBA’s 2-3% target. And while central banks in other developed economies are also expecting to miss their targets in 2023, they are plotting a clearer return to target in 2024.

The figure above shows the most recent inflation forecasts from other central banks in developed economies (noting that the RBNZ is likely to lift its forecast for 2022 and 2023 by around 0.2ppts when it updates its forecasts later this month due to a sharper than expected increase in September quarter inflation rise).

The figure clearly demonstrates that – at least in eyes of central banks – Australia’s inflation picture is not more benign than in other developed economies. Inflation is also still rising in Australia (up from 7.3% in the September quarter), whereas most other developed economies are forecasting lower inflation by end 2022.

Other central banks are taking a more aggressive approach to rate rises. Markets and central bank guidance indicate that even for economies like Canada, New Zealand and the UK, which have higher household debt exposures to short term interest rates, the terminal policy rate is likely to settle at least 1ppt above the RBA’s likely terminal rate.

The inflation forecasts for 2024 are particularly interesting: Canada (2.0%); New Zealand (2.2%); the UK (1.4%); and the US (2.3%).

These central banks are forecasting a much more emphatic return to target in 2024 than the RBA’s forecast.

The more cautious approach from the RBA raises the prospect of a further entrenching a ‘high inflation’ psychology as businesses and households may doubt the RBA’s commitment to returning inflation to the target zone. The Governor’s statement that the Bank is aiming to return inflation to the target band “while keeping the economy on an even keel” contrasts with other central banks who accept the economic slowdown as the cost of containing inflation.

The Bank’s growth forecasts are more in line with the likely economic cost of containing inflation.

The forecast growth rates have been lowered from the August numbers, particularly for 2023. Growth is forecast at 2.9% in 2022 (down from 3.2% in August); 1.4% in 2023 (down from 1.8%); and 1.6% in 2024 (down from 1.7%).

The major source of the downward revisions is household spending which was revised down from 2.4% growth in 2023 to 1.3% – in line with our forecast of 1.2% growth.

These overall growth numbers are getting closer to Westpac’s forecasts in the out years (1.0% in 2023 and 2.0% in 2024). Our faster growth rate in 2024 relies on the RBA being in a position to cut rates by 100bps in 2024. If the RBA’s inflation forecasts prove to be correct, it will be difficult to justify rate cuts as inflation will still be outside the target zone and the unemployment rate steady.

We expect the RBA will need to lift the cash rate to 3.85% in 2023 in the face of strong inflation with the last cut likely during the first half of the year (May).

Despite lower growth, the forecasts maintain that the unemployment rate will only rise from 3.5% (revised up from 3.4%) to 4.3% by end 2024 (lifted from the August forecasts of 4.0%). With slower growth in 2023 we expect that the unemployment rate will lift to 5.2% by end 2024.

Forecast wages growth in 2023 has been lifted from 3.6% to 3.9%, still benign but more in line with our own forecast of 4.5% reflecting the tight labour markets which are likely to persist through 2023.

The Overview section of the Statement does not provide any further insights into the decision process at the November Board meeting. It reiterates the points: that interest rates had already been increased significantly in a short period of time; that the effect is yet to be seen; that slowing the pace of tightening would allow more time to assess; that drawing out policy adjustments also helps to keep public attention focused for a longer period on the Board’s resolve; and that the more frequent meeting schedule allows for smaller incremental changes. Going forward, all options are options on the table including moving in larger steps if necessary or even pausing for a period – the emphasis clearly being that policy is not on a pre-set path.

Conclusion

The revised forecasts in the Statement on Monetary Policy highlight the RBA Board’s current expectation that it will not return inflation to the target zone until 2025 at the earliest. This contrasts with the more aggressive approaches of other central banks. The risk is that a ‘high inflation’ psychology emerges and is allowed to be sustained for longer, potentially making the challenge of bringing inflation back to target more difficult than necessary.

We agree with the downward revisions in the growth outlook for 2023, particularly with respect to household spending, but we expect the unemployment rate to increase further than indicated in the RBA’s forecasts.

We remain comfortable with our call that the cash rate will increase to 3.85% by May next year, relying on steady 25bp moves.

The rate cuts we expect for 2024 are consistent with the very weak growth outlook for 2023 and 2024, which the Bank is close to franking, but the Bank’s inflation forecasts would make it very difficult to deliver given inflation would be expected to hold outside the target zone.