The September quarter inflation report has come as such a major surprise that we think the Reserve Bank Board will decide to raise the cash rate by 50bps at the next Board meeting on November 1.

The quarterly CPI print was an increase of 1.8% for the trimmed mean (the accepted measure for underlying inflation) well above market expectations of 1.5%. Annual trimmed mean inflation lifted to 6.1%yr. This is the highest quarterly and annual increase in underlying inflation since the ABS began producing estimates in 2002. Historical estimates compiled by the RBA show the quarterly rise is the biggest since 1988.

Of particular concern is the widening distribution of gains across Index components. We find that 90% of expenditure items have increased by 2.5% or more in the quarter. That compares with only 63% at the height of the mining boom.

During this period of rising inflation we have been most concerned about a strong inflationary psychology becoming entrenched in the Australian psyche. As this develops, businesses become more confident that they can raise their prices; consumers become more accepting of such action and see significant wage increases, in the context of tight labour markets, as necessary to compensate, sustaining the whole inflation process.

Evidence from the survey that pricing power is becoming widespread across expenditure items should be of considerable concern to an inflation-targeting central bank.

The Budget papers have raised the prospect of a 50%+ increase in electricity prices in 2023. This means inflation overall will remain more elevated and poses further pressures on inflation psychology.

The best way for the central bank to break this nexus is to adopt strong rhetoric and strong action.

The Board should also be concerned about the unusual nature of this cycle as the economy emerges from the pandemic. Labour markets are uncharacteristically tight while the household sector has accumulated significant savings which can buffer higher rates. Evidence from business surveys that business conditions and capacity utilisation are remarkably strong also point to unusual resilience.

We do not believe that the Board has backed itself into a corner with its surprise, lower than expected 25bp increase at the October meeting. Note the final paragraph in the October Board Minutes: “The size and timing of future interest rate increases will continue to be determined by the incoming data and the Board’s assessment of the outlook for inflation and the labour market.”

That provides ample justification for speeding up the pace of increases again in response to a significant upside shock to the inflation outlook.

It seems very likely that the RBA staff, which is providing a full update to forecasts for the November meeting, will be meaningfully lifting its inflation outlook.

We would also expect some stronger guidance from the RBA Governor’s decision statement around the outlook. More emphasis on its clear determination to return inflation to the target is likely rather than the current message of a balancing act between achieving the target and keeping the economy ‘on an even keel’. Perhaps the line “Members saw this path to achieving this balance as a narrow one clouded in uncertainty” may not figure in the narrative going forward.

The discussion on policy deliberations in the October Minutes pointed to a close-run decision between the 25bp path and continuing with another 50bp move with “finely balanced arguments.”

In discussing the case for a 50bp move, the Board noted that: “Inflation was high, broadly based and expected to increase further” and that “If the Board were to reduce the size of the rate increase …. [T]his might in turn prompt an unhelpful reaction in inflation expectations”.

The Governor clearly recognises the risks of embedding an inflationary psychology into the system.

We pointed out in a note “Unintended Consequences” (October 14) that there had been a significant lift in Consumer Sentiment and House Price Expectations following the decision to pivot to a 25bp move.

With markets and the media, to date, not embracing the prospect of a 50bp move in November there can be expected to be an appropriately adverse impact on Confidence to a decision to go by 50bps.

If the inflation report had been in line with expectations, then continuing the sequence of 25bp moves would have been appropriate. But not responding firmly to this genuine shock would risk the impression of a central bank that is less than fully committed to the inflation task.

This would risk further embedding a high inflation psychology into the Australian economy.

The level of interest rates does not appear to be a major issue for the Board.

When considering the October decision the Board described the cash rate, which at the time was 2.35%, as “not at an especially high level.” With the rate now at 2.6% there is still genuine uncertainty as to whether the Board views that level as above ‘neutral’.

The Governor has referred to ‘neutral’ as a positive real cash rate with the nominal component being assessed as 2.5% – a nominal cash rate above 2.5%.

A recent speech by Assistant Governor Ellis set out the RBA’s estimates of neutral in more detail – the conclusion from nine separate models used to generate estimates is that the average neutral rate appeared to be around 1% real or 3.5% nominal. But the Assistant Governor did emphasise that the neutral concept was most useful as a long-term guide and was not applied mechanistically to policy, along the lines of the ‘short term’ and ‘long term’ real concept deployed at one point by the Federal Reserve.

A decision to push the cash rate to 3.1% would certainly, in our view, put policy firmly in contractionary territory but the academic discussion is not definitive.

The Board decision to only raise rates by 25bp in October was also partly to assess the effect of the significant cumulative increase to date. Without the inflation shock that was a defensible position but given the risks to inflation psychology we have set out above, that strategy seems to be no longer appropriate.

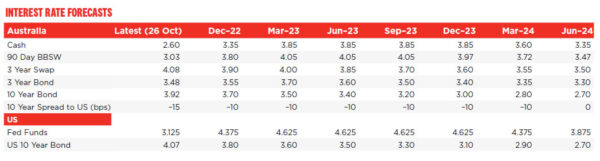

Looking forward, after the 50bp move in November we expect a further 25bp move in December but with no meeting scheduled for January there will be a two month break to provide some time to assess the cumulative impact of rapid rate increases.

By the time of the February meeting, the Board will have raised the cash rate by only 25bps over the previous three months since the November move – an adequate and appropriate break.

We were impressed with the argument in the October Minutes that: “Dragging out policy adjustments would also help to keep public attention focussed for a longer period on the Bank’s resolve to meet the inflation target.” That is a reasonable view in a context where inflation is gradually easing while remaining above the target but not when inflation, as we saw in the latest report, is surging.

The wording in the Minutes gave more prominence to the global economy than we had seen in the past. The concluding paragraph noted that: “The Board will continue to monitor the global economy, household spending, and wage and price setting behaviour.”

Recall that the meeting was held at a time of the huge volatility in financial markets associated with reactions to the UK minibudget. Those concerns have largely settled down. Recent GDP data out of China has also exceeded market expectations. While there will no doubt continue to be justifiable global concerns, the immediate issues that were likely to have framed the Board in October have eased.

We obviously have considerable concerns about the eventual impact of these policies on Australians. Without doubt the Reserve Bank shares those views.

But globally, central banks have correctly signalled the overwhelming need to rein in inflation pressures – a delay in achieving that objective will only lead to unnecessary additional pain further down the road – as Australia experienced during the deep recession of the early 1990s following its failure to address the inflation issue during the 1980s.

The inflation report has clearly highlighted that Australia is not different to other countries. Inflation in Australia looks set to exceed US inflation by the end of the year.

The RBA faces the same inflation challenges as other central banks.

A decision to speed up the rate hike cycle in November is the appropriate action.