Summary

- We look for the FOMC to deliver its fourth consecutive 75 bps rate hike at the conclusion of its meeting on November 2. Inflation continues to run much too hot for the FOMC, and the labor market remains extraordinarily tight.

- The odds of a 100 bps rate hike on November 2 are low, in our view. Although some Committee members may favor a 100 bps hike, an increase of that magnitude does not appear to be a consensus view.

- Financial markets have become volatile in recent weeks, raising some questions about the outlook for Fed policy. But we think the probability is low that the FOMC will opt for a rate hike that is less than 75 bps. The market is fully priced for 75 bps, and most Committee members believe that financial markets are generally functioning properly at present despite its recent volatility.

- In our view, the most important aspect of the November 2 FOMC meeting will be how the post-meeting statement and press conference frame policy considerations ahead. The FOMC could begin to stress the cumulative effect of tightening, which could signal that it is preparing to shift to a slower pace of rate hikes in the meetings ahead. Indeed, we are starting to hear more caution slip into the remarks of some Fed speakers.

Along with our estimates for key inflation and jobs data to soften ahead of the December meeting, the more cautionary notes we are beginning to hear from some policymakers leads us to expect that the November meeting may very well deliver the last 75-bps hike this cycle, and that the Fed is likely to step down to “only” a 50 bps hike in its final meeting of the year.

The Fed’s Barrage on Inflation Continues

Anyone hoping that the FOMC’s barrage of 75 bps hikes would come to end by now likely will be sorely disappointed at the conclusion of the FOMC’s upcoming meeting on November 2. We expect the FOMC will deliver its fourth consecutive 75 bps hike next week, bringing the fed funds target range to 3.75-4.00%.

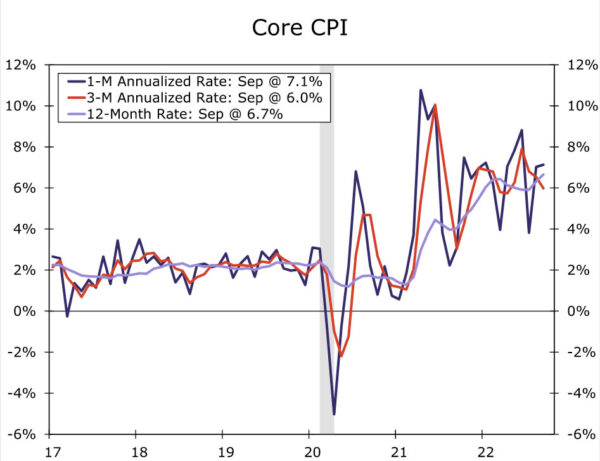

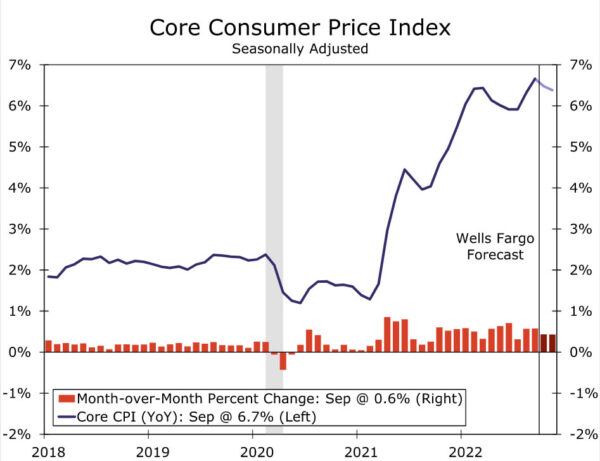

Fed officials all appear to be on the same page: inflation remains much too high, and risks are still skewed to the upside. For months now, Committee members, including Chair Powell, have been looking for “compelling evidence” of inflation moving down. That evidence has yet to materialize. All three of the major U.S. inflation indices—the Consumer Price Index, PCE deflator and Producer Price Index—surprised to the upside in their most recent prints. Most glaringly, the core CPI advanced another 0.6% in September, consistent with a 7.1% annualized rate of price growth and above both the 3-month and 12-month pace (Figure 1). Notably, the strong upturn came from services inflation picking up further speed, which more than offset the highly-anticipated softness in goods prices. All in all, the trend in inflation has yet to turn, let alone approach a level at which the Fed could be reasonably comfortable.

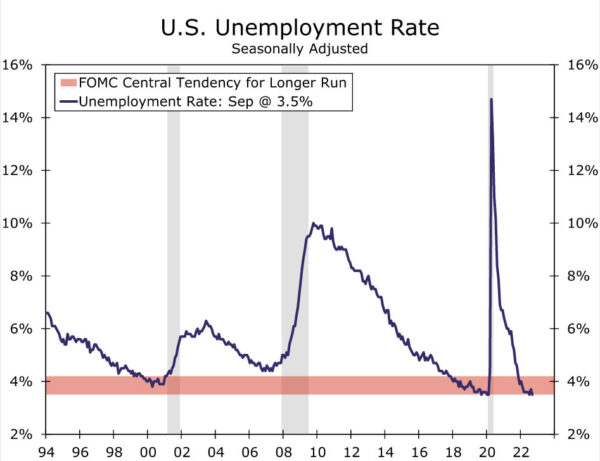

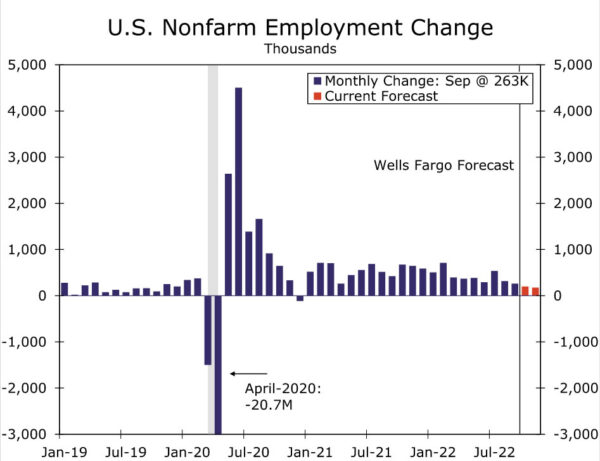

There are also no signs that the Fed’s inflation and employment mandates are in tension at present. The unrelenting pace of inflation comes with what is still an extraordinarily tight labor market. The unemployment rate ticked back down to 3.5% in September to match a 52-year low as a robust rebound in labor force participation remains elusive (Figure 2). Job growth has slowed in recent months, but even September’s gain of 263K, the smallest in 18 months, remains well above last cycle’s average of 185K. Other signs of demand for workers have cooled since the spring, including job openings and hiring plans, but remain notably higher than when the unemployment rate was this low in the prior cycle. Similarly, average hourly earnings growth has eased slightly, but at a 4.4% annualized pace the past three months, continues to run above a rate consistent with 2% inflation.

The probability of a 100 bps rate hike on November 2, as implied by market pricing, is only 10% or so as of this writing. We agree that the odds on a full percentage point rate increase in the target range for the federal funds rate are low. Although some of the more hawkish members of the FOMC may be in favor of a 100 bps rate hike, an increase of that magnitude does not appear to be a consensus on the Committee. As we discuss in more detail below, some Fed officials are starting to indicate that the FOMC will soon need to move more cautiously. But we do not think the FOMC is set to deliver a rate hike of “only” 50 bps next week. Not only does the high rate of inflation at present support the case for another 75 bps rate hike, but financial markets are fully priced for an increase of that magnitude. A smaller increase could lead to a significant “risk on” rally in financial markets, which could thwart the Fed’s efforts to cool off the economy. Moreover, there has been few indications from Fed officials in public comments that they are ready to slow the pace of tightening at this time.

Will Financial System Stress Influence the FOMC?

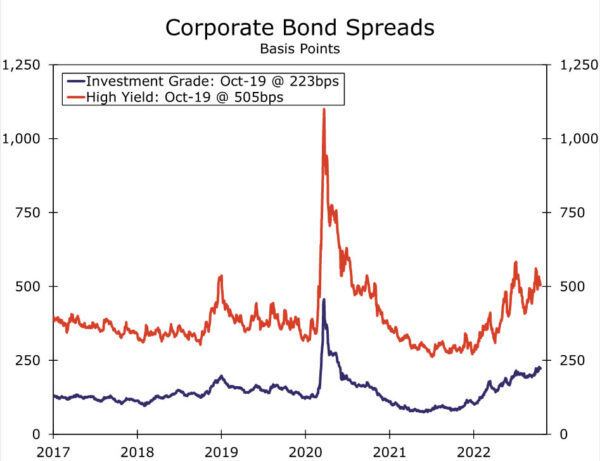

Global financial markets have become increasingly volatile in recent weeks, which has raised questions about how Federal Reserve officials will proceed with their intended path of monetary policy tightening. In the United States, equity markets have contributed to the volatility. The S&P 500 index has fallen 5.1% since the end of August and is down 21.8% this year. Bond prices have plunged as markets have repriced expectations of future monetary policy actions, and credit spreads have widened (Figure 3).

Some financial market pain is a normal part of monetary policy tightening. Monetary policy primarily impacts the real economy through changes in financial conditions, such as interest rates, credit spreads and equity prices. That said, the pace of monetary policy tightening by the FOMC this year has been stunning. As recently as early March, the Federal Reserve was still buying bonds. Yet less than eight months later, 75 bps rate hikes have become the norm, and the Fed is reducing the size of its balance sheet by up to $95 billion per month. Furthermore, with inflation remaining stubbornly high, it has become increasingly clear that monetary policy will need to become even more restrictive in the coming months via a higher fed funds rate and a smaller central bank balance sheet. Many fear that something will “break” in the financial system if the Federal Reserve continues to tighten policy at such an aggressive pace.

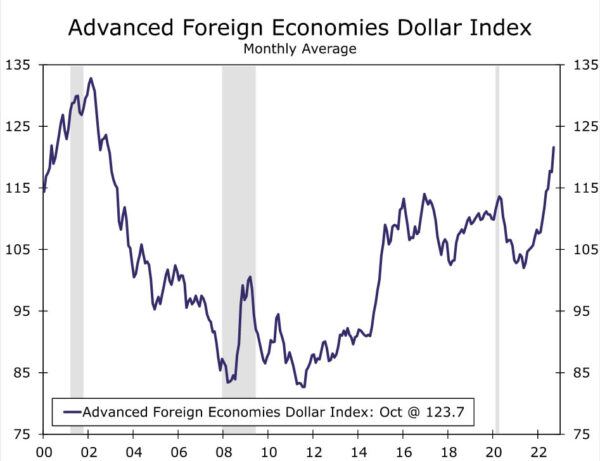

A recent episode outside the United States offered an example of what could go wrong. The prospect of much tighter monetary policy in the United Kingdom, paired with a proposed easing of fiscal policy by the short-lived Truss government, led to a sharp upward move in long-term interest rates. Eventually, the Bank of England was forced to carry out temporary purchases of long-dated U.K. government bonds to “restore orderly market conditions” amid the interest rate surge that threatened to cause a crisis for the U.K. pension system and, perhaps, the broader U.K. financial system. It remains to be seen whether this remedy has solved the problems or merely kicked them down the road. Elsewhere, worries have mounted regarding everything from Treasury market liquidity to the U.S. dollar, which has climbed to a 20-year high against a basket of other major currencies (Figure 4).

At this point in time, the consensus among Fed officials appears to be that critical financial market plumbing remains operative despite some bumps in the road. Governor Waller recently characterized himself as “a little confused” by the worries over financial stability risks, saying that “while there has been some increased volatility and liquidity strains in financial markets lately, overall, I believe markets are operating effectively.” Cleveland Fed President Mester’s view in a recent interview was that “there’s no evidence disorderly market functioning is going on at present.” New York Fed President John Williams acknowledged that market liquidity was lower due to significant uncertainty surrounding the outlook for monetary policy and the global economy, but he noted that “core markets are functioning, continue to function reasonably well.” The latest FOMC minutes made a similar claim, asserting that “the markets for Treasury securities and agency MBS continued to function in an orderly manner, though liquidity conditions in both markets remained low, reflecting elevated interest rate uncertainty.”

That said, most FOMC participants appear to be cognizant of the risks. In the same speech, President Williams noted that Fed officials need to watch these developments very closely, and President Daly of the San Francisco Fed recently argued that “we definitely don’t raise rates until something breaks.”

In our view, it is not surprising that financial market volatility is high and market liquidity has deteriorated accordingly. The economic outlook is far more uncertain than usual, and this leads to a broad range of potential outcomes with which financial market participants must grapple. But with important markets such as the Treasury market still functioning reasonably well given the circumstances, we doubt recent developments are enough to derail the Fed’s aggressive policy moves at this juncture.

What the November Tea Leaves Could Say for December

While the recent stress in financial markets does not appear to be enough to alter the FOMC’s pace of policy tightening in November, it likely does argue for a slower pace in the not-too-distant future. Supersized 75 bps rate hikes made sense when the FOMC was playing “catch up” on rates, but with the fed funds rate rapidly approaching the core inflation rate and forward-looking measures of the economy showing signs of a pending cool down, a more moderate pace of rate hikes may soon be in order. This in turn should help reduce interest rate uncertainty on the margin and could help improve financial market stability, with the latter helping to ensure that the Fed has the breathing room it needs to complete its fight against inflation.

Therefore, in our view, the most important aspect of the November FOMC meeting will be how the post-meeting statement and press conference frame policy considerations ahead. We suspect Chair Powell to reiterate that quelling inflation remains the FOMC’s utmost priority, and that the FOMC will “keep at it until the job is done.”

However, we also expect to see signs of the FOMC approaching a crossroad in its campaign to battle inflation. Monetary policy famously works with a lag. To that end, increased emphasis on the significant tightening done in short-order this year could begin to position the FOMC for a slower pace of tightening as soon as its December 14 meeting, even as inflation is still expected to be well-above target. After all, the purpose of front-loading hikes is to quickly get policy close to where it would ultimately need to be and then to let the effects of higher rates take their course.

The most impactful place we could see this consideration show up in November would be in the post-meeting policy statement. The statement could perhaps see the addition that when “assessing the appropriate stance of monetary policy, the Committee will continue to monitor the implications of incoming information and cumulative policy adjustments for the economic outlook” (bolded text our insertion). Chair Powell could further indicate that the cumulative tightening by the Committee this year is taking on greater weight in the Committee’s policy deliberations by including in his opening press conference remarks more than just a passing reference to the need to “at some point” slow rate hikes. Mentioning the need to also account for monetary policy tightening globally would further hint that the FOMC may nearing the point when it is ready to ease its foot off the brake at least slightly.

Our own view is that the FOMC will downshift to “only” a 50 bps hike at its December 14 meeting. We are starting to hear more caution slip into the remarks of some Fed speakers. Notably, Vice Chair Brainard in a recent speech stressed that the effects of tighter Fed policy this year was already working to temper demand and was “being amplified by concurrent foreign tightening.” Policy needed to move forward “deliberately” to learn the effects of cumulative tightening in her view. Kansas City Fed President Esther George, a voting member of the Committee this year, expressed concern that a string of jumbo rate hikes “might cause you to oversteer and not be able to see those turning points.”

We also expect to see more material weakening in economic activity generally, and the jobs market and inflation in particular, ahead of the FOMC’s December 14 meeting. The FOMC received only one additional reading on CPI and nonfarm payrolls between its September and November meetings. But some softening in core inflation and a slowdown in hiring should become more obvious by our estimations in the two CPI reports (Figure 5) and the two employment reports (Figure 6) that will be received prior to the FOMC’s December meeting.

However, a downshift in the pace of tightening from 75 bps per meeting to 50 bps per meeting should not be conflated with a full pivot on policy. Rather, it would be the first step in an effort to tame inflation with a bit more precision. The FOMC will therefore need to carefully message that it remains firmly committed to reducing inflation, while highlighting the progress made at getting policy to a position that is better able to achieve that outcome.