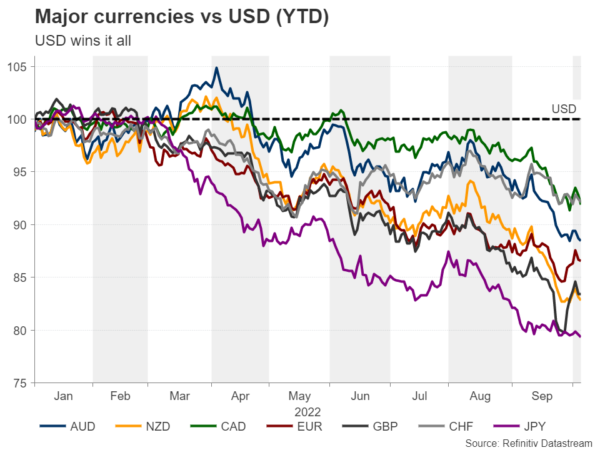

The US dollar has had a stunning run, gaining more than 15% against a basket of other major currencies – according to the DXY calculation – since the start of the year. For some developing countries though, the greenback’s surge has made servicing dollar-denominated debts a herculean task, and with several currencies, even major ones, hitting new record lows or lows last seen decades ago, there is a question that’s maybe popping more often into investors’ heads nowadays: What will it take for the US dollar to lose its crown?

The post-covid chronicles

Before answering that question, one must first understand what has been constantly fueling the greenback’s tanks, at least for the last year, and actually, it hasn’t been a single force or catalyst, rather than a blend of interconnected developments, ranging from very high inflation and monetary policy responses to anxiety over the global economic performance.

With many economies still licking their wounds after their reopening from strict covid-related lockdowns, supply shortages led to a spike in consumer prices, which central bankers mistakenly dismissed as transitory. They were thereby caught off guard when inflation continued to persistently accelerate, forced to respond around a year ago, with the central bank to first press the hike button being the RBNZ. And if covid-traumatized economies and accelerating inflation were not enough for central banks to deal with, in February Russia invaded Ukraine, adding to the already elevated uncertainty.

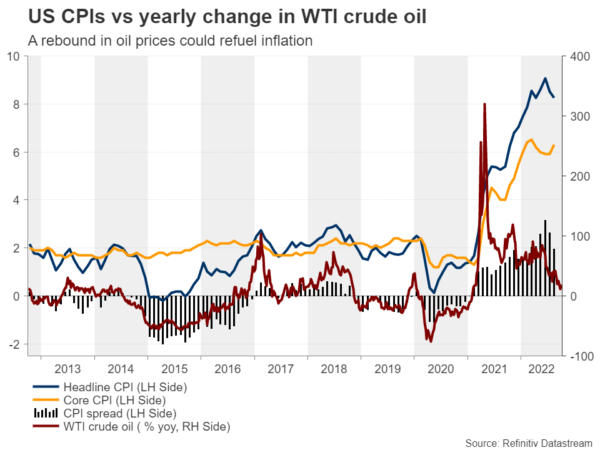

With Russia curtailing energy supplies to Europe in response to the imposition of sanctions, oil and gas prices skyrocketed, adding even more fuel to inflation’s flames, and thereby deepening the global economic wounds, especially in Europe and the UK. Combined with a battered property sector and renewed lockdowns in China, this left central bankers no other choice than to raise rates faster and more aggressively.

Mon. policy and safe-have flows keep the dollar’s tank full

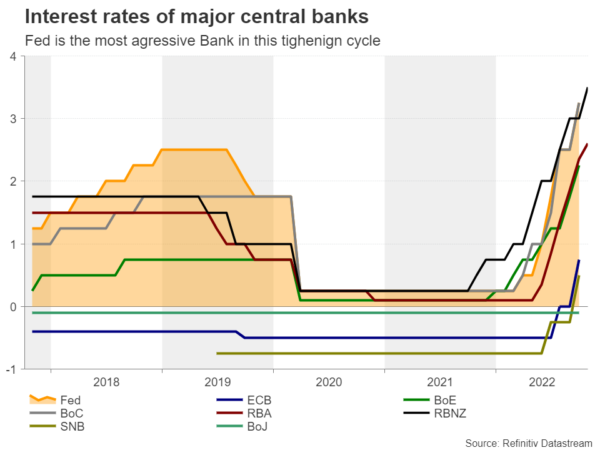

In this race, the frontrunner is the Fed, raising rates faster and to higher levels than other major central banks. Currently, interest rates in New Zealand are higher than in the US, but that’s because the RBNZ already hiked in October and the Fed still hasn’t. According to market pricing, there is an 85% chance for another 75bps hike by the Fed at its upcoming gathering, but even a smaller 50bps increment is enough to place it back first. Rates in Canada are on the same level with the US, but Canadian policymakers are now expected to slow down their hikes from here onwards.

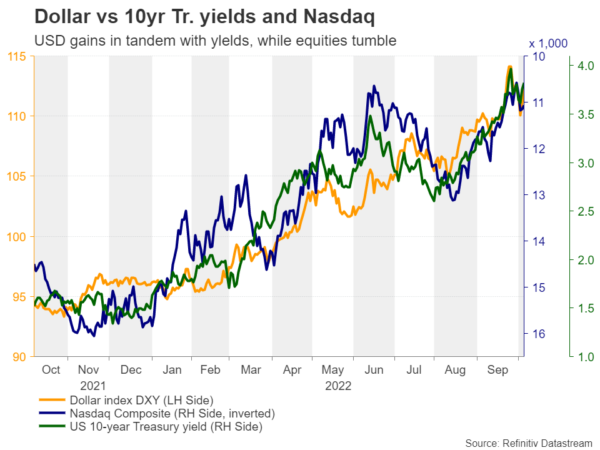

So, higher interest rates – and thereby Treasury yields – in the US compared to other major economies have been the main driver behind the greenback’s current uptrend. The co-driver is safe haven flows. The US dollar is the world’s reserve currency and the denomination of many international business deals, which makes it the default safe-haven currency. A safe haven is an asset that investors seek shelter in during periods of anxiety and market turbulence; and as already mentioned, there has been plenty of that lately. With major central banks around the world raising interest rates fast to tame inflation, investors’ anxiety worsened due to fears that tighter financial conditions will add to the likelihood of a global recession, prompting them to sell other currencies and buy dollars.

Market vs Fed: one must give in

Having all that in mind, it now becomes much easier to identify what may need to happen for the US dollar to run out of fuel and reverse its uptrend.

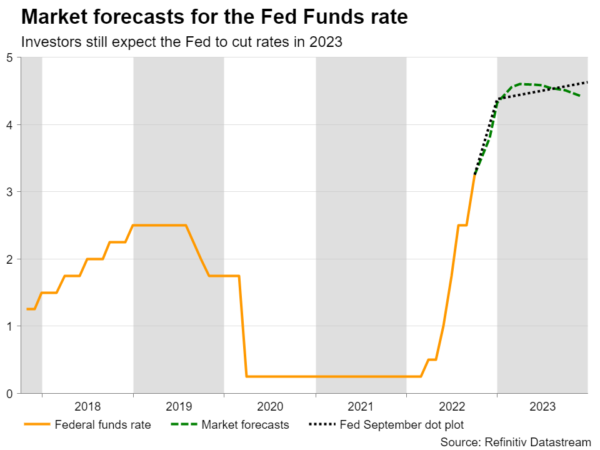

Getting the ball rolling with monetary policy, investors believe that the Fed will stop raising interest rates in March at around 4.6%, inline with the Fed’s own projection for 2023. But still, despite Fed officials keep sounding ultra-hawkish, pushing against the case of a rate cut next year, market participants continue to see rates 20bps lower by November.

This divergence between the market and the Fed near the end of next year is the room that the dollar has for strengthening further if indeed Fed officials keep appearing in their hawkish suits. So, for the greenback to trade significantly lower one must give in. Either the Fed softens and admits that interest rates could be reduced next year, or the market brings up its projections and stops pricing in any 2023 cuts.

The former case appears to be straightforward, but if the market revises up its rate-path projections, it is reasonable to expect more dollar strength rather than a sell-off. Therefore, if the Fed retains its current hawkish plans, the only additional boost the dollar would receive would come from the market revising its rate expectations higher, to catch-up with those of the Fed. But following such a boost, there would be no reason for future hikes to drive the dollar higher, if those hikes have already been discounted by the market.

Improving economics and geopolitics also needed

But will this be enough for the king to be dethroned? Probably not. Changes on the global-growth front and geopolitical landscape are also required. Oil and gas prices may have come off their highs, but with the war in Ukraine still raging and Russia supplying very little to Europe, a harsh winter could boost demand for heating energy, resulting in a rebound and thereby more inflationary pressures. In turn, central banks could eventually harden their efforts to bring inflation to heel, raising rates even faster and hurting their economies even more.

For investors to abandon their safe-haven positions and start building up risk exposure, either the conflict in Ukraine needs to end with Russia restoring to full capacity supply to Europe, or the winter ends up softer than expected. But any of these scenarios needs to also be accompanied by encouraging economic data, not only in terms of improving economic growth, but also in terms of meaningful easing in inflation around the globe.

For now, the uptrend remains intact

For now, the uptrend in the dollar index remains intact. Although the index pulled back after hitting a new 20-year high last week, it remains above the uptrend line drawn from the low of February 6, as well as above the 109.25 barrier marked by the high of July 10. A rebound from around there could result in another test at the 20-year high of 114.75, the break of which would confirm a higher high and perhaps pave the way towards the 118.80 zone, marked by the high of June 2002.

The move signaling that the bears have gained the upper hand in the near term may be a dip below the 109.25 zone and a break below the aforementioned uptrend line. This could allow the bears to dive towards the low of August at 104.70. If they are not willing to stop there, they could then aim for the 101.25 area, marked by the low of May.

Synopsis

Putting everything under one roof, if there comes a time when central banks do not need to hike by 50, 75 or 100bps, the economies are showing signs of recovery and geopolitics have taken the back seat, global equities could rebound, yields could come off their highs and thereby, the dollar may lose its crown.