Summary

- We had been forecasting that the FOMC would raise its target range for the federal funds rate by 100 bps more between now and early next year. But two developments have caused us to revise our forecast higher.

- First, the economy is showing signs of resiliency, which will necessitate more monetary tightening to slow growth sufficiently to bring inflation back toward the Fed’s target of 2%.

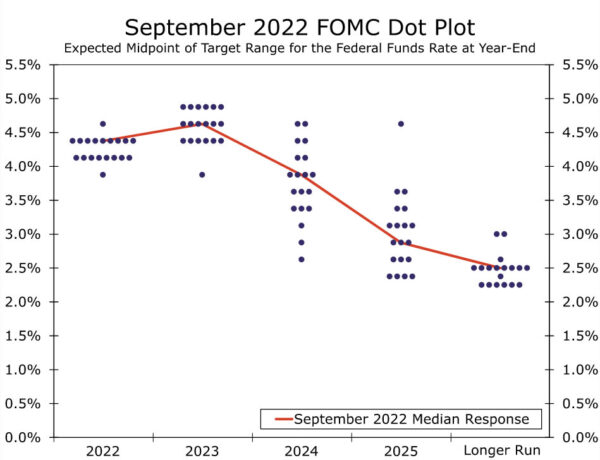

- Second, the FOMC appears willing to do “whatever it takes” to rein in inflation. In that regard, the so-called dot plot now shows that the vast majority of Committee members believe that 100 bps to 125 bps of further tightening is warranted by the end of the year. Furthermore, most policymakers expect a few more rate hikes early next year.

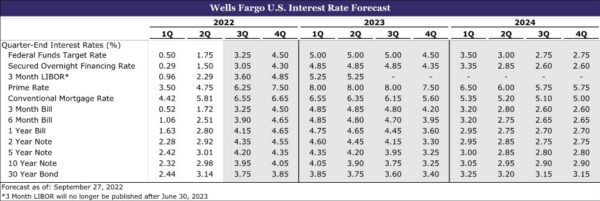

- We now look for the FOMC to hike its target range for the fed funds rate by 75 bps at the November 2 meeting and by 50 bps at the policy meeting on December 14. We think the Committee will tighten further early next year with 25 bps rate hikes at both the February 1 and the March 22 meetings. If realized, the target range for the fed funds rate would top out at 4.75%-5.00% in March 2023.

- In our view, the FOMC will not cut rates at the first sign of economic weakness to ensure that inflation is moving convincingly back toward target. But with the economy in recession, the unemployment rate rising and inflation receding considerably, we expect the FOMC will reverse course in the fourth quarter of next year. Specifically, we look for the Committee to cut rates by 50 bps in Q4-2023 with another 175 bps of easing by Q3-2024.

Skyrocketing inflation has caused the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) to tighten monetary policy significantly this year. Specifically, the FOMC has raised its target range for the federal funds rate by 300 bps since March, the fastest pace of rate hikes in more than 40 years. We had been looking for the Committee to hike rates by another 100 bps by early next year. But recent developments have led us to believe that even more tightening lies ahead, and we now forecast that the FOMC will raise rates by another 175 bps before it is finished tightening policy.

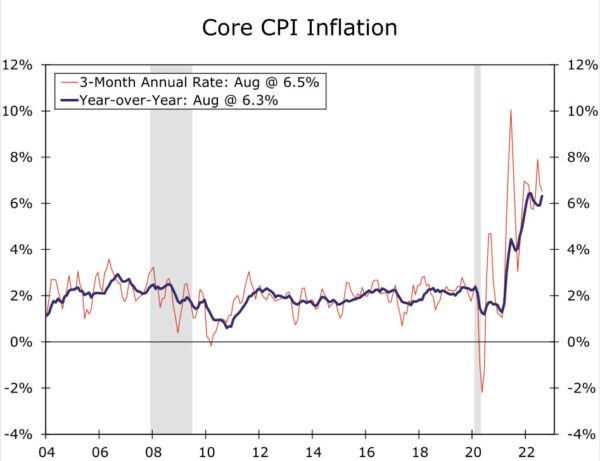

The update to our forecast reflects, at least in part, the apparent resiliency of the U.S. economy in recent weeks. Nonfarm payrolls rose by 315K in August, well above the average monthly increase of roughly 190K that the economy generated during the long expansion of 2010-2019. Tightness in the labor market has pushed wages significantly higher, with average hourly earnings up more than 5% over the past year. Not only have sizable wage gains helped to sustained consumer spending—real consumer spending likely rose again in August—but they are not consistent with an inflation rate of 2%, which is the Fed’s target rate. In that regard, the core CPI rose at an annualized rate of 6.5% between May and August (Figure 1).

Our updated forecast for the fed funds rate also reflects the Fed’s apparent willingness to do “whatever it takes” to rein in inflation. As expressed by Fed Chair Jerome Powell in his August 26 speech in Jackson Hole, “the FOMC’s overarching focus right now is to bring inflation back down to our 2 percent goal.” This commitment was visibly expressed in the “dot plot” that the Committee released at the conclusion of its policy meeting on September 21. The vast majority of FOMC members see the target range for the fed funds rate ending the year at either 4.00%-4.25% or 4.25%-4.50% (Figure 2). In short, the vast majority of policymakers envision either 100 bps or 125 bps of rate hikes over the final two policy meetings of 2022. Furthermore, most Committee members envision more tightening in 2023. Our previous forecast does not seem to be consistent with the FOMC’s most recent thinking and increased resolve to wring out inflation.

Our updated forecast for the federal funds rate is shown in Figure 3. We now look for the Committee to raise rates by 75 bps at the November 2 meeting and by another 50 bps at the December 14 meeting, which would take the range for the federal funds rate to 4.25%-4.50% by mid-December. But with the core rate of PCE inflation also up 4.5% in December by our estimates, the real federal funds rate (i.e., the nominal fed funds rate deflated by the rate of core PCE inflation) would still not be positive. In our view, the FOMC would need to get the real fed funds rate into positive territory to slow the economy sufficiently to bring inflation convincingly back toward 2%. This movement into positive territory occurs early in 2023 as the FOMC continues to tighten policy—we look for 25 bps rate hikes at the meetings on February 1 and March 22—and as inflation slowly recedes. We look for the real fed funds rate to climb to about 1% in the second quarter, which we estimate will be restrictive enough to push the economy into recession by mid-year.

As we noted in our last monthly U.S. Economic Outlook, the FOMC has been quick to cut rates at the first signs of trouble during the past few cycles. However, we believe the Committee will be slower to ease policy during this cycle to ensure that inflation is indeed moving unmistakably back toward the Fed’s target of 2%. But with the economy in recession, the unemployment rate rising and inflation receding considerably, we look for the FOMC to reverse course in the fourth quarter of next year. Specifically, we look for the Committee to cut rates by 50 bps in Q4-2023 with another 175 bps of easing by Q3-2024. Without rate cuts, the real fed funds rate would rise further, which would not be warranted in recession, as inflation continues to recede.

We plan to publish a full forecast revision, which will include some tweaks to our growth and inflation projections, on September 30. This forecast will be posted on our website.