The Chinese economic miracle seems to have turned into a nightmare lately. With a property sector in collapse and an overleveraged banking system as global interest rates move higher at the speed of light, there is a clear risk that China might suffer a 2008 moment that infects the entire global financial system. How high is that risk and which markets would be impacted the most?

Property boom

A seismic shift is underway in China. The past couple of decades were characterized by meteoric economic growth, which was enabled by businesses and households being encouraged to take on tons of debt. It wasn’t so much an economic miracle, but rather a mirage.

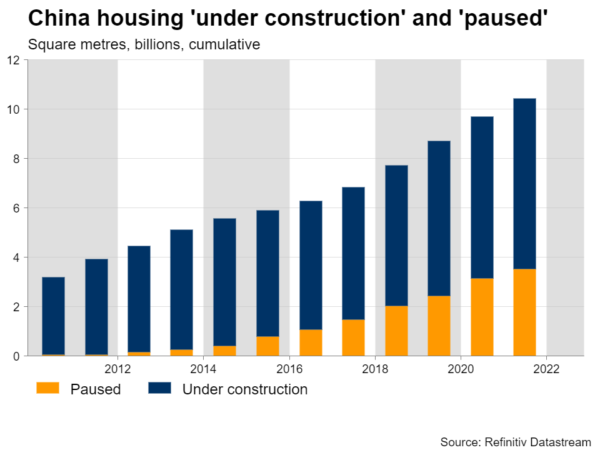

Faced with high demand and ever-rising prices because Chinese citizens saw their houses as an investment, property developers tried to build as much as possible and banks were incentivized to lend out money to everyone.

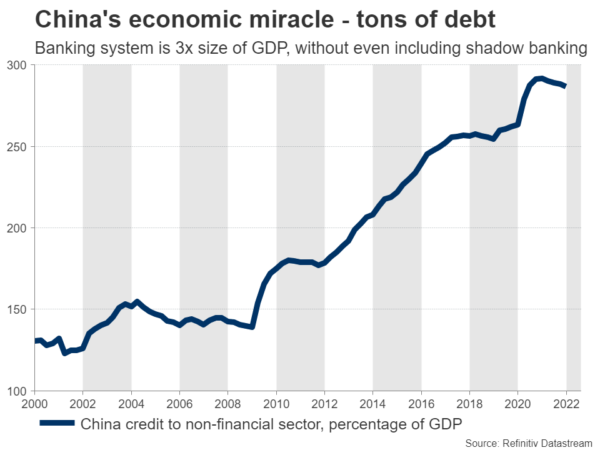

Over time, this process saw the real estate sector expand to account for around one third of national output, while the banking system issued out loans amounting to almost three times the size of the economy. And that’s before considering shadow banking, which is essentially off-the-books financing – something quite popular in China.

Mortgage revolt

Worried about an asset bubble, Chinese policymakers stepped on the brakes. They issued some rules back in 2020 that forced developers to deleverage, limiting the amount of debt they can take on. A wave of defaults ensued, shattering the long-held belief that Beijing would bail out any distressed companies to prevent contagion.

That is when the crisis entered a new phase. Around 90% of houses in China are pre-sold. Buyers are required to pay everything upfront before construction is complete – sometimes before it even starts. Worried that their developer might default and never hand over the key to their property, many people stopped paying their mortgages. It has been dubbed a ‘mortgage revolt’ and it has been spreading like wildfire.

This is a dangerous game. When loans are not being repaid and banks have a footprint that exceeds the size of the economy many times over, it usually ends in disaster. Add in the fact that interest rates are being raised at the speed of light in other countries, making foreign investors more hesitant to seek riskier investments in China, and it looks like a ticking time bomb.

This risk has been reflected in the nation’s junk bonds, which are trading near record lows. Investors see a lot of default risk in those bonds and want to be compensated for holding them.

Hammer and dance

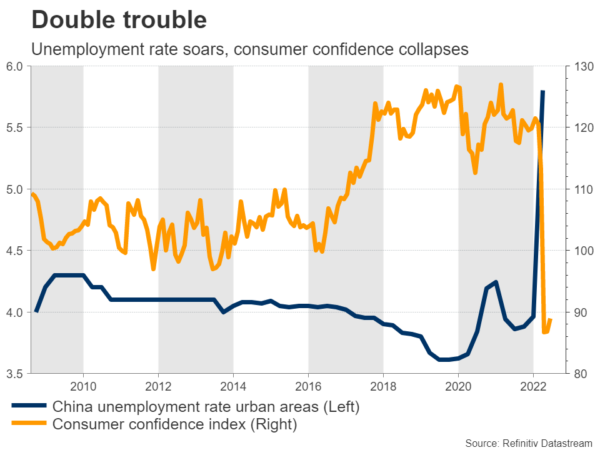

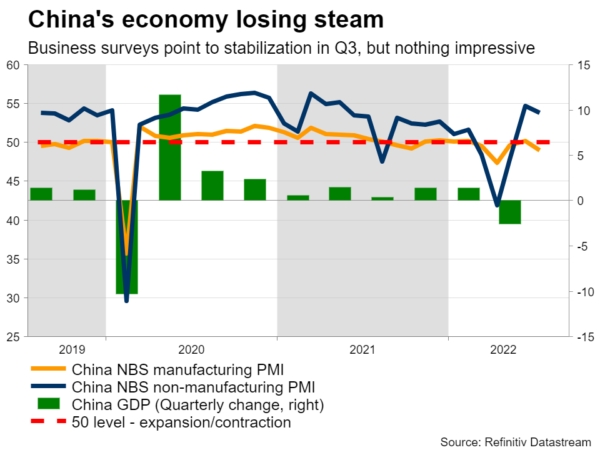

A spiraling property crisis is not the only risk facing China. Local authorities are still pursuing a ‘hammer and dance’ strategy with covid lockdowns, enacting strict restrictions whenever outbreaks are detected in some area. The economic fallout was evident during the second quarter, when the economy contracted.

Although the latest business surveys paint a more positive picture for this quarter, they are still consistent with an economy that is stalling and employment indicators suggest that companies are cutting workforce numbers to cope. Consumer confidence is already running at record lows.

And the situation abroad isn’t great either. Europe has been crippled by the energy crisis and while the US economy is holding up better, it is also losing steam. That’s a threat for Chinese factory demand, which the latest data suggest is already rolling over.

Market implications

China is the world’s second-largest economy, with deep trade ties in every country. Even though it still has soft capital controls in place, it is almost certain that any crisis would not stay contained within its borders for long. Even the Federal Reserve warned about a domino effect that could infect America in its latest Financial Stability Report.

If the situation truly escalates, that would send shockwaves across every asset class. Stock markets could get hit hard, especially those in Asia as traders slash their risk exposure to the region. Currencies like the Australian and New Zealand dollars would likely crumble as well, since the entire business model of their economies relies on exporting commodities to China.

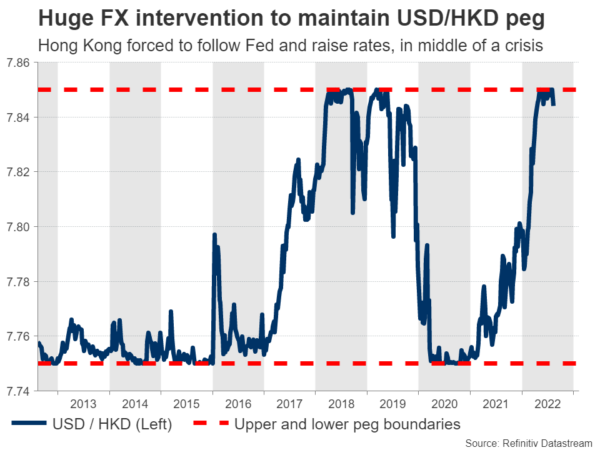

The Hong Kong dollar could get ravaged too. It is already testing the weaker end of its peg with the US dollar and the local authority is burning through its FX reserves to maintain this fix. If the selling pressure becomes even greater, they might decide it is not worth defending and simply abandon it, or at least allow the currency to depreciate.

Across the risk spectrum, the Japanese yen would likely benefit from such a scenario as traders take shelter in defensive assets and global bond yields retreat. For similar reasons, gold could come back into fashion. On the contrary, other commodities like industrial metals would probably suffer.

Mind the bailouts

All told, this is just a toxic cocktail, with local banks being incredibly exposed to a property market that is going downhill, mortgages that aren’t being repaid, and global interest rates moving higher to amplify all the stress while the Chinese economy stalls.

If there is a silver lining, it is that the Chinese government holds a lot of cards. It might be able to stop the contagion, at least initially, if it decides to bail out the most distressed entities before the domino effect truly begins. The People’s Bank of China is also likely to reduce interest rates further in an attempt to counter the increase in global rates.

Only time will tell whether the policy response will be enough. For now, this seems like the most underappreciated risk surrounding the global economy – the real ‘grey swan’.