The collapse of the Japanese yen continues, and so far, there are no signs of a trend reversal. The rise in the Yen is often linked to capital flight from risky assets, and the weakening is a sign of increased demand for risky assets. But that explanation hardly fits with what is happening now. We likely see the start of a significant reassessment by the markets of Japan’s position in the financial system. In a worst-case scenario, this may turn into a debt crisis in the Land of the Rising Sun and be an even bigger disaster for financial markets than the eurozone debt crisis of a decade ago.

The starting point for the weakening of the Yen was at the start of February. At that time, equities were in demand as a haven for capital to maintain the purchasing power of investments.

The flow into equities was interrupted by the war in Ukraine but accelerated in the last couple of weeks on signs that these events have hyped up the processes that were taking place before. And these processes are now most visible in the dynamics of the Japanese yen against those currencies where the central bank can respond adequately to inflation.

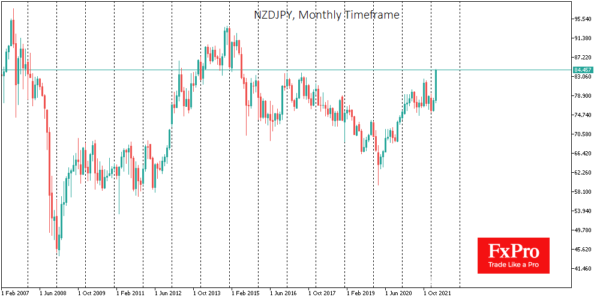

Since the start of February, the USDJPY has risen by 6.5%, and almost all this increase has taken place since March 7th, taking the pair back to levels last seen at the end of 2015. A much more impressive rally is taking place in the Aussie and Kiwi against the Yen. Since the start of February, they have soared by more than 12%. So far this month, the strengthening is the largest in 11 years for AUDJPY and in more than 12 years for NZDJPY.

The interest rate differential game, which was so beloved by traders in Japan before the global financial crisis, has found a second life. Australia and New Zealand have the economic potential to raise interest rates, as they are experiencing a surge in exports due to the boom in their export prices.

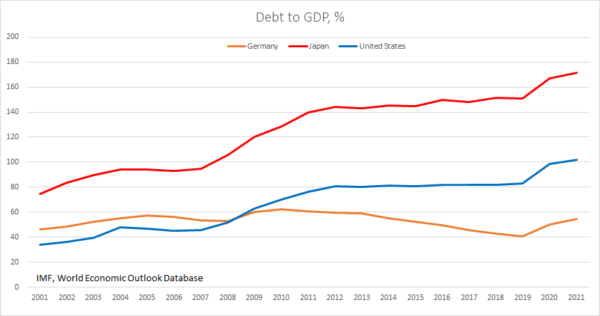

However, the situation in Japan looks considerably more alarming, as Japan’s debt-to-GDP ratio has risen by 77 percentage points to 170% since the financial crisis. Permanent QE from the Bank of Japan has kept government debt costs down but doesn’t solve the problem.

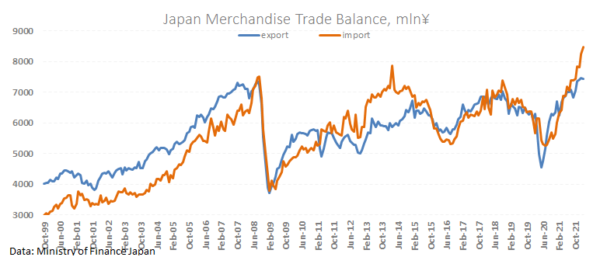

In the last decade, Japan has turned into a net commodity importer due to its growing dependence on energy and metals and increasing competition from China and Korea. The exchange rate should act as a natural mechanism to stabilise trade in this situation.

But this adjustment is difficult for debt-laden Japan because selling currency would de facto mean selling bonds denominated in that currency. Under these circumstances, the Bank of Japan either must openly accept that it will finance the government (i.e., increase purchases despite inflation) or soften QE. The first option risks triggering a historic revaluation of the Yen. The second option would deal a blow to the economy and finances by raising questions about whether Japan can service its debt.