Summary

Tensions tied to the Russia-Ukraine situation have intensified in recent days. Although we do not have any particular insight into conditions on the ground or wish to speculate on the mindset of leaders involved, assessing the potential economic and financial market reaction to an escalation is still a valuable exercise. In our view, global economic growth is not at risk should Russia and Ukraine enter recession as a result of conflict and/or international sanctions. However, oil prices could move higher as a result of Russia supply disruptions, which could weigh on purchasing power and result in energy shortages, particularly within the European Union. Oil prices are a key influence for Russia, and current supply/demand dynamics suggest oil prices could move higher, especially if sanctions are imposed on Russia. Should oil prices remain steady or move higher, we believe the Russian economy and local financial markets will be more protected relative to 2014 even if sanctions are imposed, while the ruble selloff will likely be more contained.

Russia-Ukraine Tensions Shouldn’t Disrupt Global Growth

Headlines surrounding Russia and a possible invasion of Ukraine continue to intensify. Rhetoric and rumors have created confusion as to the state of affairs on the Ukrainian border and whether the likelihood of military conflict in Ukraine is rising or not. Financial markets have been keenly focused on Russia-Ukraine developments. Over the past few weeks global equities, government bonds and currencies have been volatile as the situation has evolved. Equity prices around the world have been choppy, while sovereign yields and currencies have swung sharply in both directions as news on the situation changes. Should the current climate continue (i.e. no material escalation or de-escalation of tensions) we would expect financial markets to remain on edge, and for media headlines and political rhetoric to be a key source of volatility. While we do not have particular insight into conditions on the ground or wish to ascertain the mindset of leaders involved, assessing the potential economic and market impact of an escalation is still appropriate. Unfortunately, precedent for this type of scenario exists. There are nuances, but Russia’s annexation of the Crimean Peninsula in 2014 can act as a guidepost for how the global economy as well as more specific country and regional economies could be impacted. We can also use the 2014 Crimea invasion to gauge how currency markets, in particular emerging market currencies, could respond.

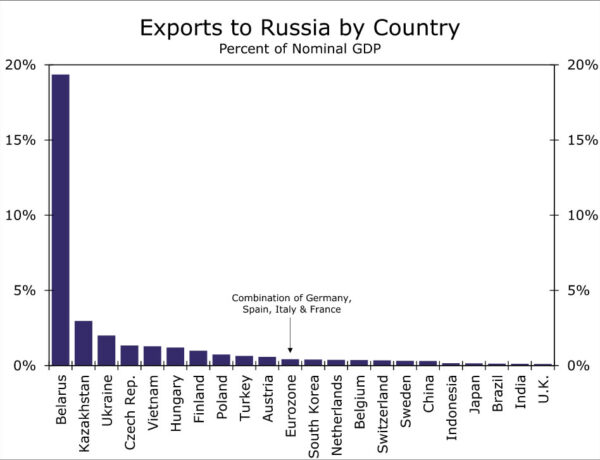

When we say “an escalation” we are being opaque by design. Obviously, “an escalation” can be interpreted many ways and result in a variety of outcomes; however, in our view, given the types of escalations and international sanctions response that appear to be the most likely at this time, we believe the impact of a Russia-Ukraine escalation on global economic growth would likely be minimal. For 2022, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecasts Russia’s share of global GDP to be 1.6%. As far as Ukraine, the IMF expects the local economy as a share of global output to be just 0.2%. In a scenario where military conflict between the two nations and new sanctions plunge Russia and Ukraine into deep and prolonged recessions, a combined share of 1.8% of global economic output is not large enough to materially disrupt global economic growth. Even if we look at potential contagion through trade linkages with other nations, the spillover effects of recession in Russia and Ukraine would likely be limited as well. Ukraine is not a significant trading partner for any major or moderately large economy, and hence the contagion effect of an Ukraine recession would not be significant. Russia on the other hand has a bit more exposure to European Union countries as well as the Eurozone. Countries such as Hungary, Finland and Poland export goods to Russia, and while still small, those exports are not totally insignificant being worth between 0.75%-1% of each country’s GDP (Figure 1). Russian demand for goods and services also stretches to the Eurozone, where we estimate the region’s exports to Russia are equivalent to 0.4% of overall Eurozone GDP. While the Eurozone is economically significant in a global context, in our view, exposure to Russian demand is not material enough to disrupt the Eurozone economy or place much downward pressure on global economic growth. Russia and the United States have been decoupling for years and trade linkages between the two economies are minimal. While Russia and China have improved and strengthened ties over the years, China only exports products to Russia worth around 0.25% of its economy. Other major economies such as the United Kingdom and Japan are also not very reliant on Russian demand and would likely not experience any major economic disruptions from a Russia recession.

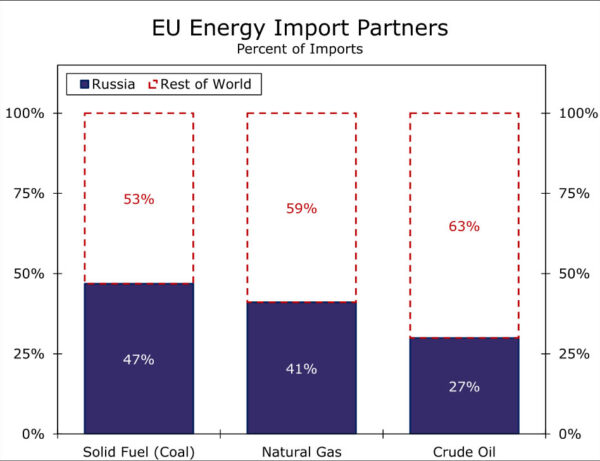

However, Russia’s involvement could have more indirect effects on the global economy due to Russia being one of the world’s largest oil producers and energy exporters. Right now, global oil production is around 100 million barrels per day. Of that 100 million barrels, Russia produces about 10 million barrels. Should a military conflict lead to new international sanctions being imposed on Russia, those sanctions could target Russia’s ability to export oil and, should that oil supply be taken out of the market, a supply/demand imbalance could form and oil prices would likely move higher. Given many of the world’s economic growth engines – including China, Japan and the United Kingdom and European Union – are net energy importers, higher oil prices could result in slower growth. In addition, higher oil prices would also increase the cost of living and could result in reduced household consumption. Of the major economies, the European Union seems to be particularly exposed not only to higher prices, but also specifically to Russian oil and to the possibility of energy shortages, an already budding problem across the European continent. Recent data indicate the European Union sources a high percentage of its energy from Russia. 47% of European Union coal, 41% of natural gas and 27% of oil imports come from Russia (Figure 2). In a scenario where Russian energy exporters become targets of new sanctions, the European Union could experience energy shortages that crimps manufacturing and raises the cost of living. Inflation is already rising across Europe, and should energy shortages push energy prices sharply higher and reduce household purchasing power even more, EU economic activity could soften.

Russia Could be Protected This Time

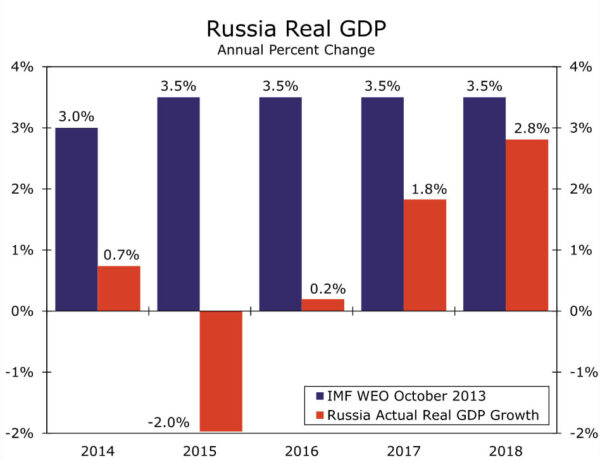

As far as the economic impact specifically to Russia, we can draw insight from the episode in 2014; however, we also note that the current scenario is not necessarily an apples-to-apples comparison. Russia’s economy was certainly disrupted by the invasion into Crimea and the subsequent international sanctions; however, 2014 also marked a supply and demand imbalance in commodity markets that resulted in an oil price slump (i.e. more supply than demand). Those same supply and demand dynamics may not be in place today. For now at least, if an imbalance does exist, demand probably is greater than supply. In theory, when demand is greater than supply oil prices should rise, so an oil price shock might not be something Russia’s economy will need to contend with this time around, just sanctions. With that said, the dual shock of sanctions and lower oil prices pushed Russia’s economy into recession following the 2014 Crimea invasion, an economic downturn that lasted through 2016. To give a sense of how much this dual shock weighed on the economy, we can look at IMF forecasts at the end of 2013 compared to actual annual growth rates. In the IMF’s October 2013 World Economic Outlook (published before the annexation of Crimea and the fall in oil prices), IMF economists forecast Russia’s economy to grow 3% in 2014 and 3.5% from 2015-2018. In response to lower oil prices and the effects of sanctions, actual annual growth rates came in much lower. In 2014 Russia’s economy grew only 0.7%, contracted 2% in 2015, and expanded 0.2% in 2016 before demonstrating a more robust recovery later on (Figure 3). In our view, the oil price shock had a more significant impact on the Russian economy, but disentangling the exact impact of low oil prices from sanctions is difficult. We do believe, however, sanctions would place downward pressure on growth. With that said, the severity of the sanctions would likely determine the magnitude as well as the longevity of the hit to Russia’s growth prospects in 2022, as well as in years to come.

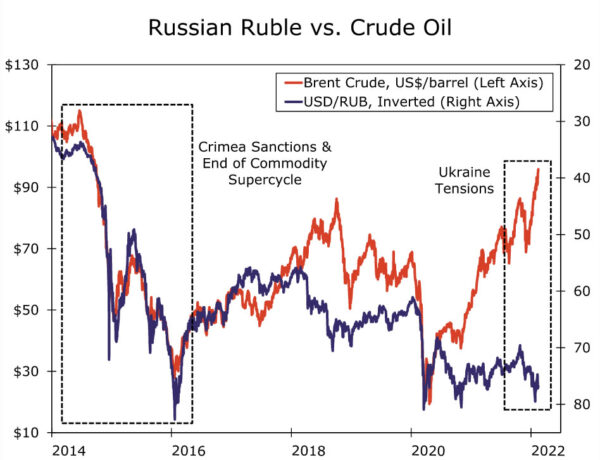

We also believe the severity of sanctions would be a key driver of the ruble over the short-to-medium term. While we will refrain from prognosticating on the specific types of sanctions that could be imposed, sanctions designed to disrupt Russia’s economy as well as integration and inclusion in the global financial system would likely be the most damaging for the path of the ruble. We can also use the 2014 crisis as a benchmark for how the ruble could perform against this geopolitical backdrop, but with the same caveat that oil prices were very influential over the currency in 2014, and the same oil price action may not occur in today’s environment. From 2014-2016, on a peak to trough basis, the Russian ruble depreciated over 50% (Figure 4), the worst performing currency in the world over this period. In our view, the majority of the ruble’s selloff from 2014-2016 was driven by the collapse in oil prices, and we would not expect a selloff of the same magnitude should an escalation occur. However, we do believe sanctions played a role in the ruble’s devaluation. Should harsh international sanctions be imposed on Russia, we believe the ruble can come under more pressure than we currently forecast; however, we do not believe the currency will test all-time lows against the U.S. dollar experienced toward the end of 2016.

Along with the ruble, we also believe regional Eastern European emerging currencies would come under pressure. Currencies such as the Polish zloty, Hungarian forint and Czech koruna could sell off, while the Turkish lira and South African rand could also be vulnerable in this scenario. We expect that other emerging market regions such as Latin America and Emerging Asia would not come under as much pressure. Trade linkages between these regions and Russia are not significant, and while sentiment could weigh on emerging currencies broadly, we believe elevated energy prices could support currencies such as the Brazilian real, Mexican peso and Colombian peso. We also believe underlying fundamentals across Emerging Asia are strong, and while Asian countries are mostly energy importers and high energy prices could impact current account balances and growth prospects, we expect any volatility to be muted and short-lived.