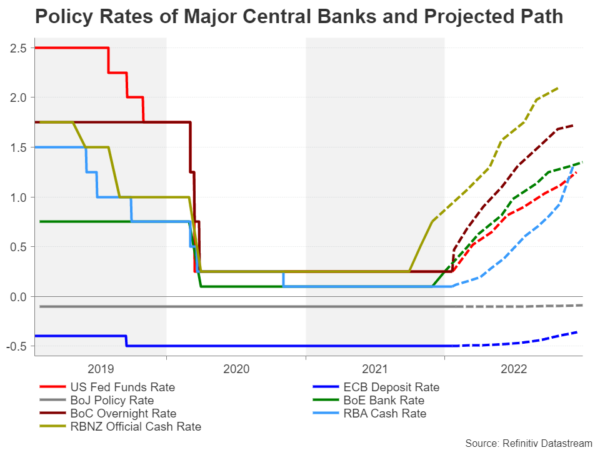

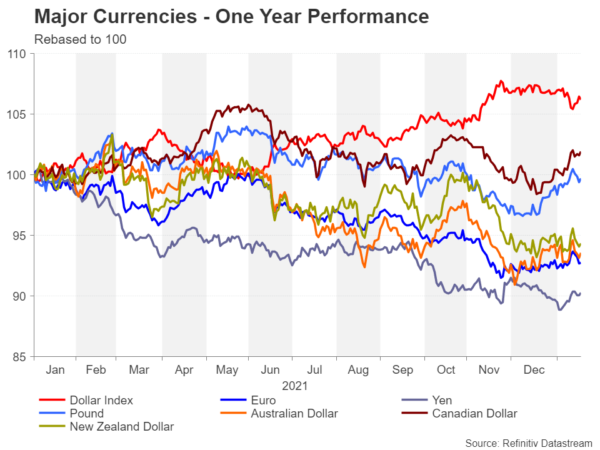

It is now universally accepted that the pandemic-induced surge in inflation is no longer looking very transitory and central banks around the world are starting to hit the panic button. The US Federal Reserve is not only talking about rate hikes but wants to begin quantitative tightening soon. The Bank of England and Reserve Bank of New Zealand have already lifted rates at least once. Even the ultra-dovish European Central Bank is keeping its options open in terms of possibly having to speed up its normalization plans. There are some exceptions, but these aside, the global tightening race has yet to provide much competition to the mighty US dollar.

The great inflation scare

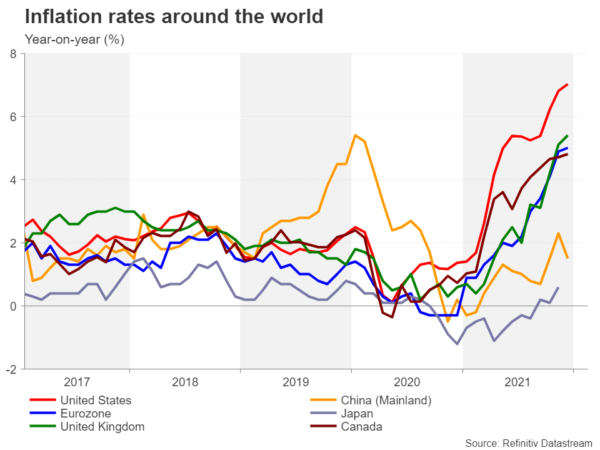

Policymakers have pinned the high inflation problem on a number of factors. Everything from the initial economic reopening effect to the low base effect of 2020 to the rally in energy prices has been blamed for the unexpected spiral in inflationary pressures. However, almost one year on after inflation first started to explode higher, not only is it more evident that the main root of this price surge is the breakdown in global supply chains, which has simultaneously exposed how complex and interdependent they had become from years of globalization, but that the supply bottlenecks are unlikely to clear very quickly.

Central banks – whose biggest fear is inflation expectations becoming entrenched – are finally waking up to this realization. The Fed has made several hawkish pivots over the last six months. Yet, it probably remains the most behind the inflation curve as the United States is seeing the biggest and broadest price spikes on a wide range of goods and services. Combined with the worker shortages that are pushing up labour costs, the risk of a vicious cycle of higher inflation is growing. There is now a danger that the Fed may consequently be forced to step on the brakes much harder, tipping the economy into recession.

Dollar and US yields stand tall

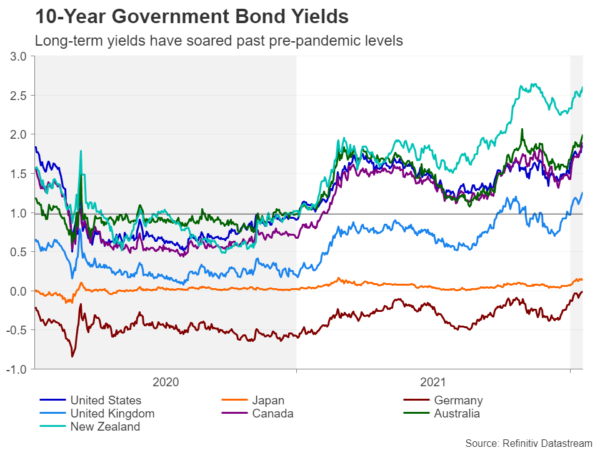

Treasury yields on both the short- and long-end of the curve have been rallying lately as the bond market is bracing for an imminent rate hike as well as the unwinding of the Fed’s $9 trillion balance sheet at some later point in the year. All this bodes well for the greenback as the Fed is moving to normalize policy at a much faster pace than many of its peers.

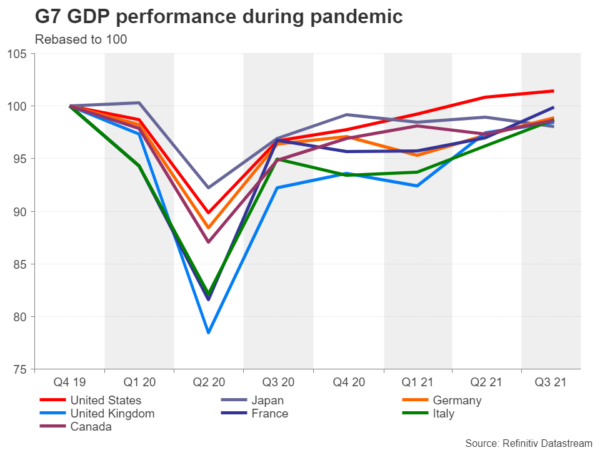

But perhaps what separates Fed tightening expectations from other central banks more is the view that the US economy is in a stronger position than rival economies to withstand interest rate increases. This doesn’t just imply a higher terminal rate, which is the level that the policy rate is anticipated to peak in the current cycle, but that there’s also less of a risk of a policy mistake.

Hence, although it might be difficult for the dollar to resume its uptrend when yield differentials with some countries are set to narrow soon, or at the very least, not widen further, it’s hard to see investors turning bearish on the currency when many of the other big economies are still lagging in the recovery and when the pandemic fog has yet to fully clear.

Europe’s stagflation worries

The lingering dark clouds over the outlook is one reason why investors aren’t as optimistic about the Eurozone, where the recovery has been weaker. Fundamentally though, even if growth in the euro area proves resilient amidst the supply constraints and energy crisis, a wage-price spiral is less likely due to the region’s high unemployment rate, and this should act as a hindrance to rising inflation, which currently stands at an all-time high of 5.0%.

However, Europe is facing a severe energy crunch, which apart from causing fuel bills to soar, it is also squeezing households’ disposable incomes, potentially weighing on consumption. Unless energy prices start to ease soon, the ECB will be compelled to act. Money markets have fully priced in one 10 basis point rate hike in 2022. The odds are rising for a second one but that may be too much of a stretch. In the worst case scenario that Eurozone inflation doesn’t come down on its own accord like the ECB is hoping it will, the risk of stagflation is quite high.

The gloomy predictions probably explain why traders remain quite bearish on the euro. It’s latest charge against the dollar turned out to be a false breakout from its sideways range and it has since slipped back below $1.14. The pound has had better luck against the greenback, managing to crack above its seven-month-old descending trendline to briefly top the $1.37 level.

UK: Cause for optimism, and caution

Inflation in the UK jumped to a near 30-year high of 5.4% in December and the jobs market is tightening fast. The Bank of England is almost certain to hike interest rates for a second time since the pandemic to 0.50% in February. More hikes are on the cards, and with UK growth expected to beat other advanced economies in 2022, there could be more gains in store for the pound.

Nevertheless, there are still some significant uncertainties for the UK outlook. Brexit is exacerbating Britain’s supply-chain crisis and energy bills are set to skyrocket in April when the price cap is lifted by the country’s regulator. While these pose upside risks to inflation, they pose downside risks to growth, raising the prospect of stagflation and holding back sterling’s advances.

Things are looking up for the loonie

Another country where the growth outlook is very positive is Canada. Like in most regions, growth is expected to take a small hit in the short term from the Omicron wave. However, higher oil prices and the strong labour market should help the economy to bounce back quickly from the latest restrictions. More importantly, Canada’s consumer price index edged up to 4.8% in December, and with the Fed readying to pull the rate hike trigger, the Bank of Canada might be emboldened to take the lead.

The odds of the BoC lifting rates as early as its January 26 meeting have soared lately, fuelling a rally in the Canadian dollar. Unusually, the New Zealand dollar has been unable to capitalize on similarly bullish rate hike bets. The RBNZ has raised the official cash rate twice already and will likely repeat the 25bps increases at each of its scheduled meetings this year.

Antipodean currencies are the surprise laggards

However, those expectations were baked in months ago and not a lot has changed since. If anything, the fresh uncertainties from Omicron and the slowdown in China have somewhat dampened the previously optimistic forecasts. The same risks are weighing on the Australian dollar too, even though the Reserve Bank of Australia is highly likely to make a hawkish shift at its next meeting.

Market pundits think the RBA, which has yet to announce an end to its QE programme, will be able to catch up in the rate hike race before the year end. But the RBA could disappoint as wage growth remains quite sluggish in Australia.

China is cutting rates

As for China, monetary policy is headed in the opposite direction as the government responded quickly to the jump in commodity and component prices, taking measures to contain the fallout – something only possible in a centralized economy. China’s CPI rate fell to 1.5% in December, giving the country’s central bank room to cut borrowing costs. Should authorities continue to ease financial conditions and micromanage the deleveraging of the troubled property sector, that could pay dividends for the rest of the world if growth starts to pick up later this year.

In the meantime, however, the weak domestic consumption is a drag on the global economy, though not so much on the yuan, which is being boosted by the record trade surplus.

Will there be an inflation shock in Japan?

Finally, in Japan, inflation may be creeping higher, but the Bank of Japan’s own forecasts don’t see it peaking much above 1% over the next couple of years. Even if inflation were to climb a lot higher, by that point, yield differentials with the US would probably have widened even further, giving the yen little scope for a rebound.

That’s not to say that inflation cannot surprise to the upside in Japan, especially if the supply-chain bottlenecks and rally in energy commodities don’t ease soon. Inflationary episodes are difficult to control and predict. Should Japanese producers decide they can no longer absorb the surging input costs, there is no telling how far they would go in passing the price burden onto consumers.

The guessing game of when inflation will peak

And it is a similar predicament for all countries. Despite most central banks now moving swiftly in removing liquidity from the financial system, inflation is hard to tame once it’s been let loose. If inflationary pressures do begin to moderate sometime in the next few months as most policymakers expect, US yields are likely to suffer the biggest correction, hurting the dollar.

However, the longer it takes for inflation to peak, the better the greenback’s chances of resuming its bullish path. Mainly because as the world’s reserve currency, the dollar stands to benefit from any risk aversion brought on by an inflation panic, while the risk of growth faltering in the US from aggressive monetary tightening would be less than in other countries.