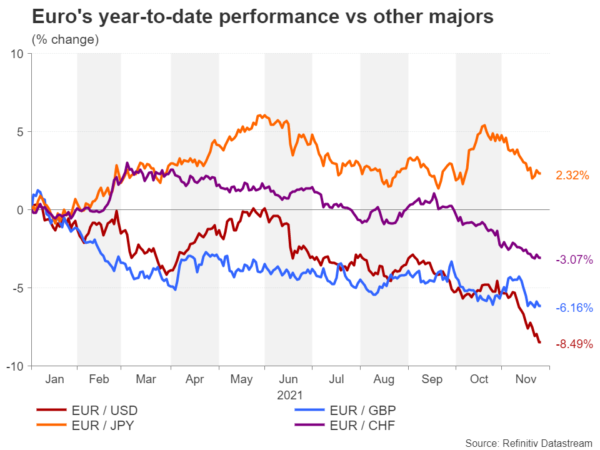

The euro’s woes just keep getting worse and worse. The single currency has ploughed more than one-year lows against the US dollar and pound, and six-year lows versus the Swiss franc. Expectations of diverging monetary policies had been weighing for some time, but now there are fresh doubts about the growth outlook that also have investors worried. The resurgence of virus cases in many parts of Europe has caught markets by surprise, endangering the euro bloc’s already fragile recovery. But is the bearish sentiment overdone, and are investors overlooking the risk of infections elsewhere following in a similar direction?

Last in the normalization race

The Eurozone economy has been making solid progress in recovering from the pandemic during 2021, yet the euro has been steadily declining against most of its main peers. The primary explanation behind the euro’s underperformance is simple. With other major economies also either on or past the road to recovery, their central banks are making plans or have already begun to normalize monetary policy after an extraordinary period of unprecedented stimulus.

The Federal Reserve recently joined the Bank of Canada and Reserve Bank of Australia in tapering its monthly asset purchases, the Bank of England could hike rates next month, while the Reserve Bank of New Zealand just raised its cash rate for the second time since the pandemic. Although it’s true that the European Central Bank has also slowed its bond purchases and will end its emergency QE in March 2022, it still has its regular asset purchase programme (APP) that has been running concurrently throughout the virus crisis. It is widely expected that the ECB will not only keep APP active for the foreseeable future but may beef it up slightly to partially compensate for the conclusion of the emergency purchases.

More crucially, the ECB is nowhere near lifting its benchmark lending rates, surpassed only by the Bank of Japan when it comes to a delayed liftoff. These expectations have been gradually taking shape during the course of the year, dragging euro crosses lower, but the bearish outlook got additional thumbs ups lately.

A double blow for the euro

First, ECB chief Christine Lagarde doubled down on the Bank’s dovish stance, warning against premature tightening. Lagarde is fast becoming the odd one out amongst central bankers who has yet to deviate from the notion that the current spike in inflation is temporary even as most of her fellow policymakers adopt a more precautionary approach.

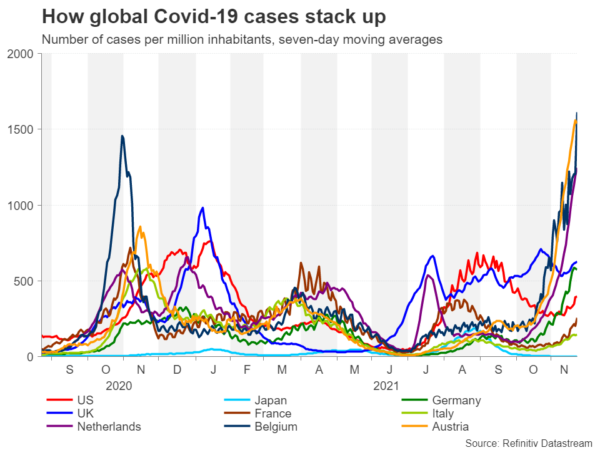

Second, infections of Covid-19 are rising rapidly in many parts of Europe. Several countries have recently announced the re-imposition of some restrictions, with many targeted at unvaccinated people. But some nations have gone into a partial or full lockdown. With winter only just starting, the virus picture could get a lot worse before it gets better. Although, as seen from subsequent lockdowns, businesses and consumers have learnt to adjust to the unfolding virus situation, the latest measures are nevertheless expected to take a toll on economic activity over the coming months.

The weaker growth outlook can only mean that there will be even less urgency for the ECB to raise rates in the next year. And despite the fact that money markets continue to price in a 10-basis point rate hike, currency traders aren’t too convinced. Even if the ECB were to put up rates, it would still be a paltry increase compared to the tightening anticipated by other central banks.

The return of lockdowns

Until now, lockdowns in a post-vaccinated world were something that had not been factored in by investors and this might be why the euro’s latest selloff has been so dramatic. After all, countries such as Britain had led the way in proving that it is possible to keep Covid deaths low while lifting almost all social distancing rules. So why are some European nations with stricter curbs than the UK being inundated with a surge in hospitalizations due to Covid?

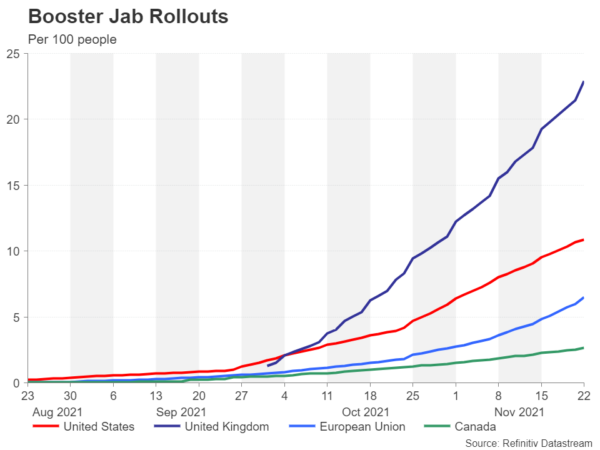

There is some evidence that suggests that the AstraZeneca jab, which accounts for most of the UK’s vaccine doses, provides better protection for the elderly. Another possibility is that there is greater herd immunity in Britain due to higher previous infections, in particular, the Delta variant spread there much early on than in the rest of Europe.

Will the US be next?

But what about the United States, could it be next in seeing a re-escalation of virus cases? New daily cases and hospitalization rates have begun to creep up and even though America’s booster program has gotten off to a decent start, it lags the UK’s rollout. There is risk that markets have become complacent against the persisting threat of the virus ever since vaccines came into the picture.

Whilst it’s not very likely that there would be renewed lockdowns in the US, some toughening in restrictions cannot be ruled in the winter months. Furthermore, as observed from previous virus waves, it only takes a blowup in infection levels for consumers to stay at home.

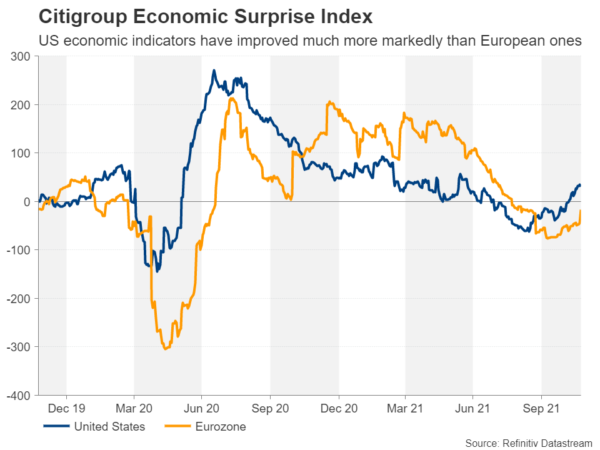

Part of the euro’s downward drive is down to the recent improved optimism for the American economy as the latest indicators suggest growth picked up at the start of the fourth quarter. Should this optimism come into question, the US dollar might lose some of its shine, boosting struggling currencies like the euro.

Too pessimistic?

Another upside risk for the beleaguered single currency is the assumption that growth will be hit hard by the current wave of measures. But with so much pessimism priced in, there’s a good chance Europe’s economies will weather this storm much better than what markets expect.

It’s also worth pointing out that large speculative investors are not overly bearish on the euro. According to CFTC data, speculators have cut their euro long positions substantially this year but were only just net short as of November 19.

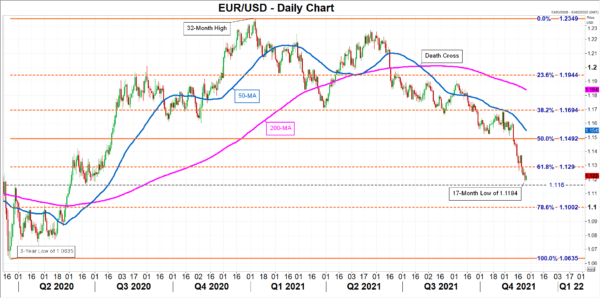

Technical indicators on the other hand, imply that the euro is oversold, at least against the US dollar. Should buyers step in, the 61.8% Fibonacci retracement of the March 2020-January 2021 uptrend will be the first critical test at $1.1290 followed by the 50% Fibonacci of $1.1492. Overcoming the latter would also help euro/dollar reclaim its 50-day moving average, which is required for eliminating the selling pressure.

However, if sentiment doesn’t turn soon and the pair breaks below the $1.1160 support, the next test for the bears will be the 78.6% Fibonacci of $1.1002. Crashing below $1.10 would reinforce the euro’s downslide as well as open the door to revisiting the March 2020 trough $1.0635.

It’s all about the ECB

To sum up, the euro remains exposed to surprises in the economic and virus data in the short-term, meaning there’s likely to be more volatility ahead. As things stand, traders may be overlooking some of the upside risks. Ultimately though, its longer-run trend will be determined by how soon the ECB joins other central banks in signalling that rate hikes are just around the corner, and that will probably be decided by whether the jump in inflation in the Eurozone ends up being transitory like Lagarde believes.