Summary

- We expect the FOMC to formally announce plans to taper asset purchases at the conclusion of their next meeting on November 3. .

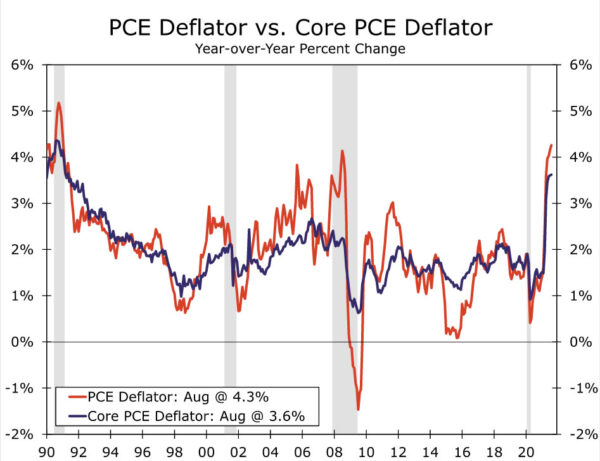

- “Substantial further progress” has clearly been made on the Fed’s inflation goal since last December when inflation was well below the Committee’s 2% target. Currently, at 3.6%, core PCE inflation is at its highest level since 1991.

- The labor market’s progress has been the hold up and kept the debate over when the Fed will taper alive a little longer. While the September employment report showed an underwhelming number of job gains, the FOMC has stressed the accumulated progress, rather than the pace of progress, in the labor market. Comments from Chair Powell and other voting members since the last jobs report have continued to signal support for an announcement at the upcoming meeting.

- We expect the Fed will reduce purchases of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities (MBS) by a respective $10B and $5B per month, beginning in early December. At this pace, the Fed would complete its asset purchase program by the end of June 2022. The Fed’s balance sheet would be slightly above $9 trillion.

- Since the last FOMC meeting, market pricing for the first rate hike has been steadily pulled forward into October 2022. If realized, the time between asset purchases ending and liftoff of the fed funds rate would be much faster than the one-year gap that occurred during the past cycle. We believe the tapering announcement is likely to come with another firm reminder that the bar for increasing the fed funds rate is much higher than it is for reducing asset purchases. Between an extended employment gap and our projected slowdown in inflation, we expect the FOMC will not hike rates until 2023.

Achievement Unlocked: Substantial Further Progress

On November 3, the FOMC will conclude its regularly scheduled two day meeting, and we expect the central bank will use this opportunity to announce a tapering of its asset purchases. More specifically, we think the Fed will begin reducing its Treasury security and mortgage-backed security (MBS) purchases by $10B and $5B per month, respectively, starting in December. If the FOMC takes a pass on a taper announcement on November 3, a December 15 announcement seems all-but-assured unless the economy completely comes off the rails between now and then. In the pages below, we lay out the case for a November taper announcement, discuss the risks to this forecast and then briefly consider other possible developments that could occur at the November 3 meeting.

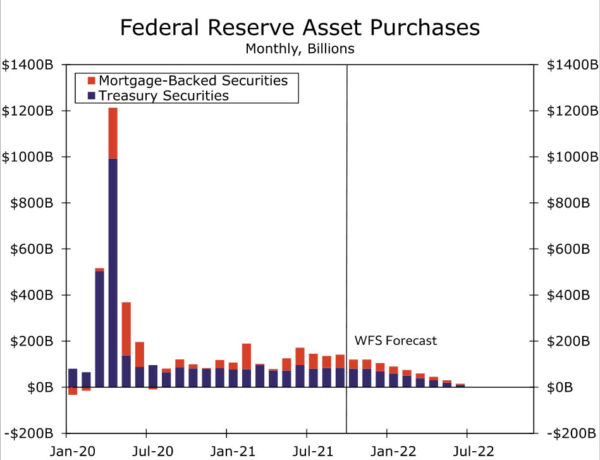

When the COVID-19 pandemic began to wreak havoc on the global economy and financial markets in March 2020, the Federal Reserve sprang into action. Among other policy actions, the Fed purchased an enormous quantity of Treasury securities and MBS in the spring of 2020. Eventually, the pace of purchases slowed and reached a monthly run-rate of roughly $80B in Treasury securities and $40B in MBS. In December 2020, the FOMC adopted new language that offered some insight into how long this pace of purchases might last. The statement from the December 16, 2020 meeting said asset purchases would continue at that pace until “substantial further progress has been made toward the Committee’s maximum employment and price stability goals.”

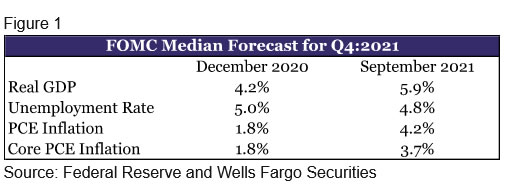

What exactly qualifies as “substantial further progress” has been hotly debated for the entirety of 2021. The inflation half of the mandate has been more straightforward to assess. Both headline and core inflation have been much stronger than the FOMC anticipated this year (Figure 1), and at 3.6% core PCE inflation is at its highest level since 1991 (Figure 2). In Chair Powell’s Jackson Hole speech in late August, he expressed his view that “the ‘substantial further progress’ test has been met for inflation.” We have no good reason to believe this has changed in the seven weeks since that speech. Inflation should not be an impediment to a November 3 taper announcement.

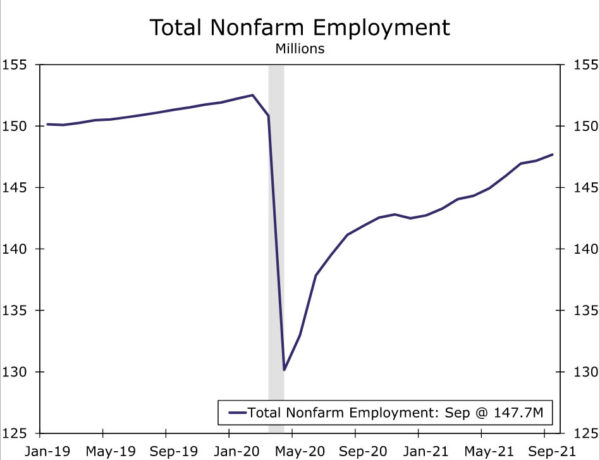

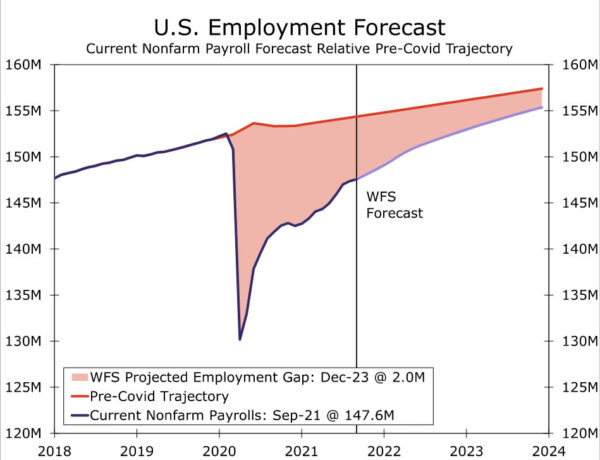

Determining whether “substantial further progress” has been made towards the FOMC’s goal of maximum employment is a bit trickier. In December 2020 when this language was adopted, the labor market had recovered 55% (12.3M) of the 22.4M jobs lost in March and April 2020. Through the first nine months of 2021, nonfarm payrolls have risen an additional 5.1 million, bringing cumulative total job gains since April 2020 to 17.4 million, or 77% of the jobs lost at the onset of the pandemic (Figure 3).

After the most recent FOMC meeting, Chair Powell was asked in his press conference what kind of September jobs report it would take to prompt the FOMC to announce a taper at its November meeting. We believe it’s worth quoting his answer in full:

“So it is, it’s accumulated progress. So, you know, for me, it wouldn’t take a knockout, great, super strong employment report. It would take a reasonably good employment report for me to feel like that test is met. And others on the Committee—many on the Committee feel that the test is already met. Others want to see more progress. And, you know, we’ll work it out as we go. But I would say that, in my own thinking, the test is all but met. So I don’t personally need to see a very strong employment report, but I’d like to see a good—a decent employment report.”

A few things jump out at us from this response. First, Chair Powell immediately noted that it is “accumulated progress” rather than any one report that matters most. He also said that, in his view at least, it would take a “reasonably good” or “decent” employment report in September for the “substantial further progress” test to be met. Was the September employment report “decent” enough? We suspect the answer is yes. Nonfarm payrolls rose just 194K in August, well-below the Bloomberg consensus of 500K. But, 194K is still above-trend job growth. Just as important, the revisions to the previous two months were a substantial +169K. Combined, the level of employment was 363K higher in September than it was prior to the data release. When paired with the accumulated progress on employment over the past 18 months, we think this clears the bar.

Tellingly, a number FOMC voters have signaled support for a November announcement since the September jobs report, including Chair Powell, Governors Clarida, Waller, and Quarles, and Atlanta Fed President Bostic. If the FOMC takes a pass on a taper announcement on November 3, a December 15 announcement seems all-but-assured unless the economy completely comes off the rails between now and then.

Tapering to Be Completed by Mid-2022

The November 3 meeting will not include an update to the dot plot or the FOMC’s economic projections, so there will be nothing new on that front. The language in the statement will almost certainly change, but unlike past meetings we doubt that parsing the statement’s language will be a big part of this meeting. Assuming that the FOMC does announce a taper, the next biggest question to be answered is what the pace of that tapering will look like.

Chair Powell has dropped some hints about what the pace of tapering might look like. In his press conference after the September FOMC meeting, he said that most participants are of the view that “a gradual tapering process that concludes around the middle of next year is likely to be appropriate.” If we use July 2022 as roughly the middle of next year, this implies the pace of tapering could be roughly $10B/$5B per month for Treasuries/MBS or it could be roughly $15B/$7.5B per meeting since FOMC meetings are about six weeks apart. The minutes from the most recent FOMC meeting suggested that most participants seemed to favor a $10B/$5B monthly pace of tapering.

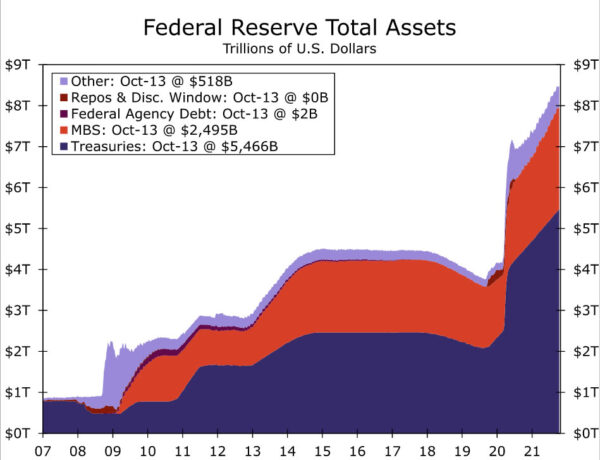

Our working assumption is that the FOMC announces a taper on November 3, with the actual tapering of purchases beginning at the start of December. From there, we assume that the Federal Reserve reduces its asset purchases each month by $10B for Treasury securities and $5 billion for MBS (Figure 4). At this pace, the Fed would complete its asset purchase program by the end of June 2022. The Fed’s balance sheet, which is currently about $8.5T, would be slightly above $9T by mid-2022 (Figure 5). Any outright balance sheet reductions are likely at least a couple of years away, and it is possible the Federal Reserve never reduces its balance and instead simply lets the economy “grow into” this $9T figure.

Fed Funds Rate Liftoff: A Much Higher Bar

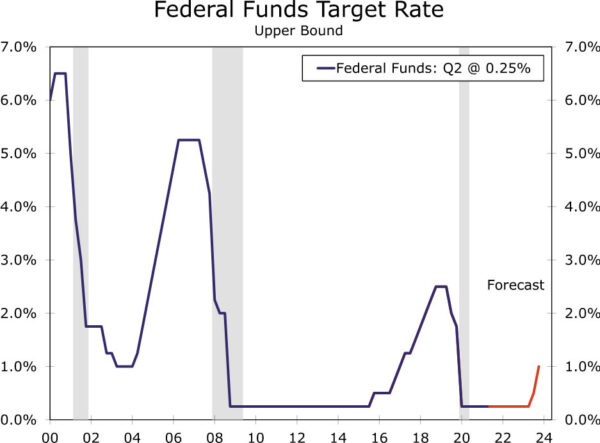

One other topic we will be listening closely for in the press conference is the path of future fed funds rate increases. Since the last FOMC meeting, market pricing for the first rate hike has been steadily pulled forward. As of this writing, a full 25bps rate hike is priced in by October 2022. If realized, this would be much faster than the one year gap that occurred between the end of the Fed’s asset purchases in December 2014 and its first rate hike in December 2015.

We think the first rate hike by October 2022 is a bit too aggressive. Numerous FOMC policymakers have made clear that the bar for rates hikes is much higher than the bar for the tapering of asset purchases. Indeed, if we return to the extended Powell quote we used earlier, the very next line in that segment of the press conference was that everyone should not confuse substantial further progress with “the test for liftoff, which is so much higher”. And in his Jackson Hole speech, Powell reminded listeners that “we have said that we will continue to hold the target range for the federal funds rate at its current level until the economy reaches conditions consistent with maximum employment.”

It is likely Chair Powell will pair the tapering announcement with another firm reminder that the bar for increasing short-term interest rates is much higher. At August’s rate of job growth it would take a little more than two years to recoup 100% of the jobs lost during the pandemic, and even then the economy would still be several million jobs short of its pre-pandemic trend. Even with our faster projected pace of job growth, we still expect the labor market to face a meaningful employment gap for the entirety of 2022 (Figure 6). In our view, this employment gap, paired with our projected slowdown in inflation, will keep the Fed from raising rates until 2023 (Figure 7).