Summary

- We think it is unlikely that the FOMC will make any major policy changes at its meeting on June 15-16. Although we do not believe the FOMC will make any changes to its current pace of asset purchases in June, the minutes of the April meeting showed that the topic was broached. The opening discussion regarding the eventual “tapering” of asset purchases likely will take place at this meeting.

- The Committee likely will upgrade its assessment of the current state of the economy relative to the statement that was released at the conclusion of the last FOMC meeting on April 18.

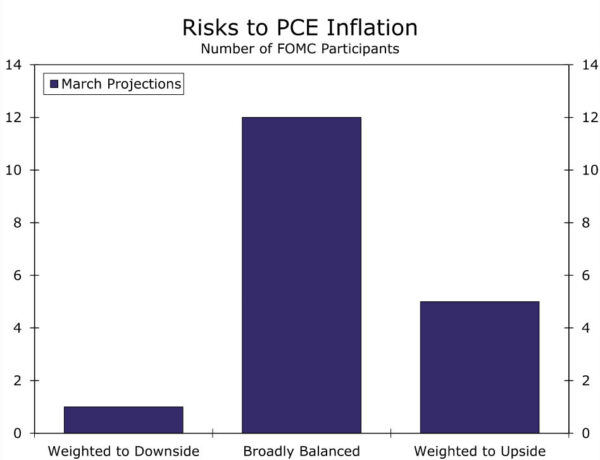

- The FOMC will release its quarterly Summary of Economic Projections (SEP). We look for the Committee to raise its forecasts for GDP growth and inflation in 2021. Of more importance to the outlook for future rate hikes will be the inflation forecast for 2022 and 2023. We expect these forecasts to show that the Fed still deems recent inflation strength as transitory, but the SEP is also likely to show FOMC members believing risks around inflation are increasingly tilted toward the upside.

- Accordingly, the “dot plot” could shift up a bit for 2023.

- Cash continues to pour into the financial system, putting downward pressure on short-term interest rates. To nudge short-term interest rates a bit higher, the FOMC could increase the rates paid on excess reserves (IOER) and on reverse repurchase agreements. But any increases in these rates, should they indeed occur, would be done for operational reasons. They should not be interpreted as a sign that monetary tightening is imminent.

Rates on Hold and No Tapering Yet, but Time Has Come for Laying Preliminary Groundwork

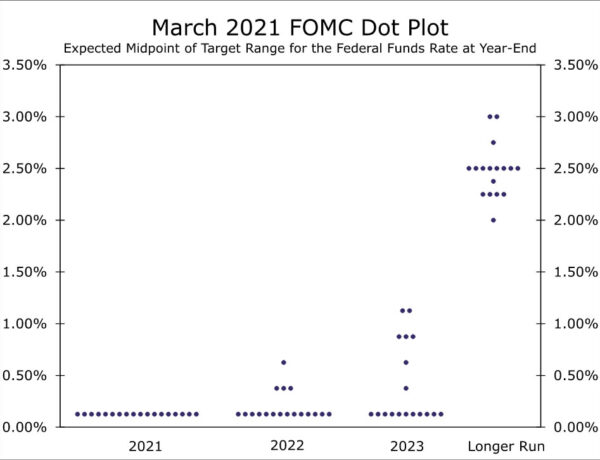

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) will hold its next regularly scheduled policy meeting on June 15-16, and we think it is unlikely the Committee will announce any major policy changes at the meeting’s conclusion. Changing the current 0.00% to 0.25% target range for the federal funds rate is not even a matter of consideration anytime soon, a point hammered home by committee members through both their submissions to the “dot plot” (Figure 1) and public statements. Where views might be evolving is with respect to the FOMC’s plans regarding the pace of asset purchases.

The Federal Reserve is currently buying $80 billion worth of Treasury securities and $40 billion worth of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) every month. Although we do not believe the FOMC will make any changes to its current pace of asset purchases in June, the topic was at least broached at the April meeting. According to the minutes from that meeting, FOMC members were optimistic enough about the economy that “a number” of them began to tread softly toward a discussion about dialing back some support for the economy. The incrementalism here cannot be overstated; these participants “suggested” that it “might be appropriate at some point in upcoming meetings to begin discussing a plan for adjusting the pace of asset purchases.” The mantra from the Fed for months has been that it would continue its current rate of asset purchases “until substantial further progress has been made toward the Committee’s maximum employment and price stability goals.”

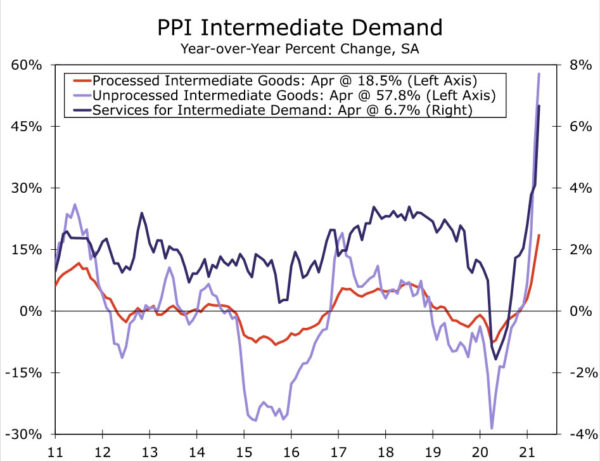

In recent weeks, the ongoing struggles of the supply-side of the economy to meet surging demand has left price pressures growing at a breakneck pace. Yet the FOMC’s adoption of average inflation targeting means the Committee can tolerate inflation above 2% for a period of time to offset periods when inflation was below that rate. So the constant references to the “transitory” aspect of rising prices signal that the FOMC currently feels little urgency to slow the pace of increased accommodation, despite a number of commodities at or near multi-year highs and wholesale prices consistently surprising on the upside (Figure 2). Until Fed officials drop references to “transitory inflation,” we maintain that the labor market would need to strengthen significantly before the FOMC starts to publicly contemplate a tapering of asset purchases. If the increase of 559K jobs that we saw in the employment report for May proves to be sustainable, then we anticipate Fed officials will warm-up more publicly to eventual tapering of asset purchases later this year with an eye toward implementation of that tapering on a conditional basis early in 2022. Early in the pandemic, Chair Powell said the FOMC was “not even thinking about thinking about” removing policy accommodation. We do not expect that sort of blanket promise at the June meeting.

The Committee likely will upgrade its assessment of the current state of the economy relative to the statement that was released following the last FOMC meeting on April 18. Incoming data in recent weeks have generally reflected an economy that is experiencing growing pains as demand outpaces supply. Core capital goods orders and shipments both exceeded expectations in April, even as the supplier deliveries component of the ISM manufacturing index rose in May to its highest reading since right after the oil embargo in the early 1970s. Although payrolls increased by only 278K in April, the 559K increase in May shows the labor market is strengthening even though the level of payrolls remains 7.6 million workers below its pre-pandemic peak. But the biggest change since April is that the share of vaccinations rose high enough for the CDC to roll back mask mandates, thus ushering in a new era in the reopening of the services economy. Revised estimates lifted the pace of first quarter consumer spending, and monthly figures for April showed nominal services spending posting a fifth consecutive monthly increase.

New Projections Likely to Relay Upside Risks to Inflation

The June meeting will bring additional insight to the Committee’s outlook and baseline expectations for raising the fed funds rate with an updated Summary of Economic Projections (SEP). We expect to see an upward revision to the 6.5% GDP growth rate for 2021 that the Committee forecasted in the March SEP and, to a lesser extent, the 3.3% growth rate for 2022. The recovery in output has continued to advance faster than anticipated, and some committee members may incorporate expectations of an additional fiscal spending plan approved by Congress in coming months.

Between slower job growth and signs that workers won’t be returning to the labor force in one fell swoop, the median estimate for unemployment at the end of year is unlikely to change meaningfully from the 4.5% projection in March. But a number of Fed officials have commented that the labor market may be tighter than the level of employment or unemployment suggest. That leaves the SEP as only a course guide to its latest thinking on the labor market, and we will be looking to Powell’s press conferences for important nuances on the labor outlook as a result.

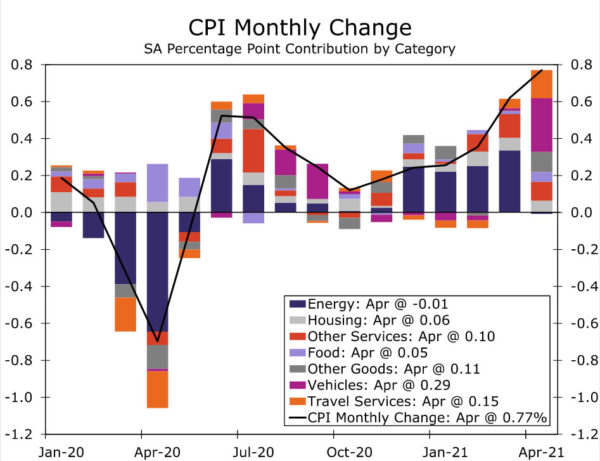

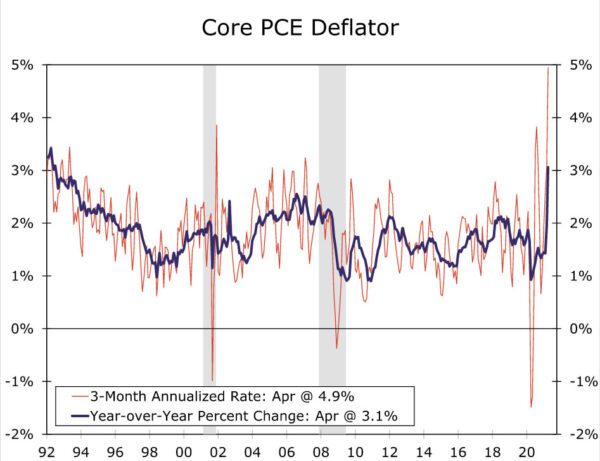

Inflation has come on stronger and faster than the Fed expected only a few months ago. In the three months since FOMC members last submitted forecasts, the core PCE deflator has risen at a 4.9% annualized rate—the fastest pace in 31 years (Figure 3). We expect to see hefty upward revisions to 2021 inflation forecasts as a result. This recent burst of inflation may convince some committee members that “substantial further progress” has been made toward the FOMC’s price stability goal of 2% over the “longer run.” Thus, these members may think that it is now appropriate to begin discussing when tapering of asset purchases can commence.

But forecasts of inflation in 2022 and 2023 will be more important for the path of the fed funds rate, and those forecasts are still likely to convey that the FOMC sees the current strength in inflation as transitory. After all, the biggest drivers of inflation over the past few months have been closely tied to the economy’s reopening and bottlenecks in industries such as motor vehicles (Figure 4). We expect the SEP will show that committee members expect inflation to slow in 2022, and that it will be running just a couple ticks above 2% through 2023. Most FOMC officials will likely see that path as consistent with inflation running “moderately above 2% for some time” to make up for lower inflation periods. However, given the marked pickup in inflation recently, we expect FOMC officials will signal that risks around inflation are increasingly tilted toward the upside (Figure 5).

Even as the current degree of inflation is expected to subside over 2022 and 2023, the recent strength and growing belief that the labor market is likely tighter than conventional measures would suggest means that a few Fed officials could very well pull forward projections for when interest rates are likely to rise. In March, 11 of 18 officials expected the fed funds rate to remain on hold through 2023, but we would not be surprised to see the number slip toward around half (refer back to Figure 1).

Short-Term Interest Rates Scraping the Bottom: Will the Federal Reserve Finally Act?

In our Flashlight Report that previewed the March FOMC meeting, we laid out the case for some technical tweaks to the Federal Reserve’s administered policy rates at one of the upcoming meetings. At the time, there was already a significant amount of cash parked in low-yielding, highly liquid vehicles like bank accounts, money market funds and Treasury bills. The pending enactment of the American Rescue Plan and the Federal Reserve’s continued asset purchases appeared set to put even more cash into the financial system. The Federal Reserve did eventually make one change when it increased the counterparty limits on its overnight reverse repo program (RRP), but thus far it has resisted increasing the rates paid on the RRP and on reserves held at the central bank.

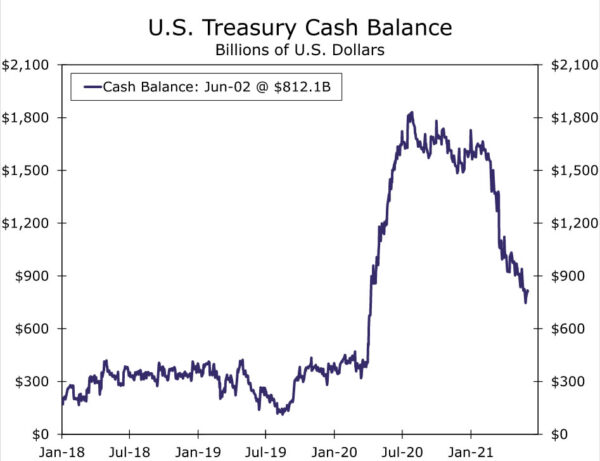

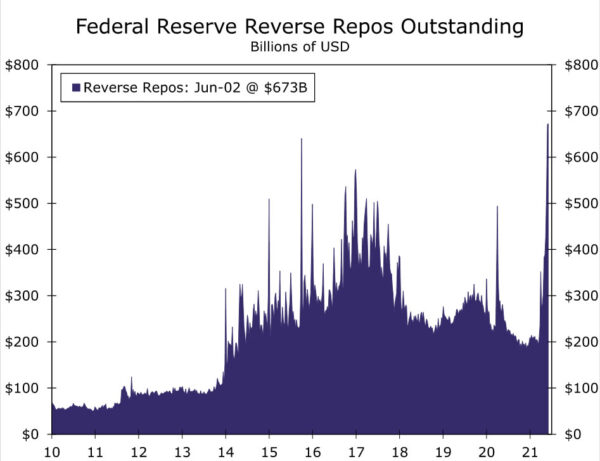

Cash has certainly continued to pour into the financial system. The U.S. Treasury’s cash balance has declined rapidly in recent months as the federal government pays out its obligations under the American Rescue Plan, such as direct checks to households, unemployment benefits, state and local aid and public health measures (Figure 6). In addition, the Federal Reserve has continued to create bank reserves and use them to purchase $80 billion of Treasury securities and $40 billion of mortgage-backed securities per month. As a result, bank reserves held at the Fed have risen by $692 billion year-to-date, while the Federal Reserve’s RRP has spiked to an all-time high (Figure 7). As a reminder, the RRP is a cash-absorbing facility where the central bank takes in cash and lends out Treasury securities on an overnight basis. These reverse repo operations pay 0% to the cash lender and serve as the ultimate “floor” on short-term overnight interest rates. Banks, money market funds and other financial service firms can always take their excess cash to the Fed and park it at the RRP, earning 0% on their money.

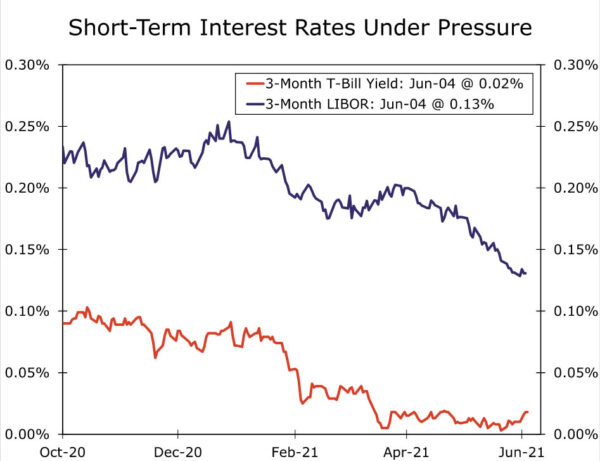

Why would so much money flow into a facility like RRP that does not pay interest? This activity implies there is a dearth of attractive investment options with similar risk profiles, and market-based, short-term interest rates signal that this is the case. The Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR), which is based on overnight repurchase agreements, has been just 0.01% every day since March 11. The effective fed funds rate has drifted down to 0.06% from 0.09% at the start of the year, and it has occasionally dipped down to 0.05% in recent weeks. Yields on Treasury bills are also historically low; the one-month and three-month Treasury bills yield just 0.00% and 0.02%, respectively. And at 0.13%, three-month LIBOR continues to set new all-time lows (Figure 8).

Thus far, these very low interest rates have not prompted Federal Reserve action other than the expanded RRP counterparty limits mentioned earlier. To some extent, this relative lack of action by the Fed makes sense. Although short-term interest rates are extremely close to zero, they have remained on the positive side of the zero lower bound. And the federal funds rate, which is the central bank’s target interest rate, has remained within the target range of 0.00%-0.25%. In the past, the FOMC has taken action when the fed funds rate has moved to within roughly five basis points of the lower- or upper-bound of its range. The current, low setting on the effective fed funds rate suggests the time for action from the Federal Reserve could be close. Fed officials likely would prefer to avoid short-term interest rates dipping into negative territory or for the fed funds rate to get too close to the bottom of the target range. It is also up for debate how long some financial services firms, particularly money market funds, will tolerate inflows that end up at the Fed’s RRP earning 0%.

To nudge short-term interest rates a bit higher, the FOMC could increase the rates paid on excess reserves (IOER) and RRP. Past increases have been by 0.05 percentage points, although they do not necessarily need to be of this size. If the RRP paid a few basis points more than 0%, this would create a bit more breathing room from the lower-bound. Critically, the Federal Reserve would be looking to bring rates just a bit higher for operational reasons and not to tighten monetary policy. A much more material increase in interest rates for monetary policy reasons is unlikely until at least 2023, in our view.