Summary

The 13.1% drop in April personal income masks broad-based growth in a variety of personal income sources that were washed out by the absence of stimulus checks. Spending wobbled as a drop in outlays on goods offset a modest increase in services spending. The PCE deflator shooting up to 3.6% is yet another inflation indicator flashing red, but remember that your base month is April 2020 when the lockdowns caused prices to drop.

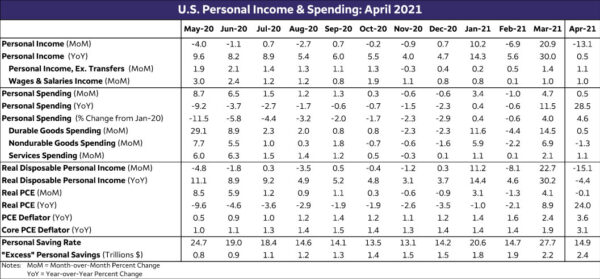

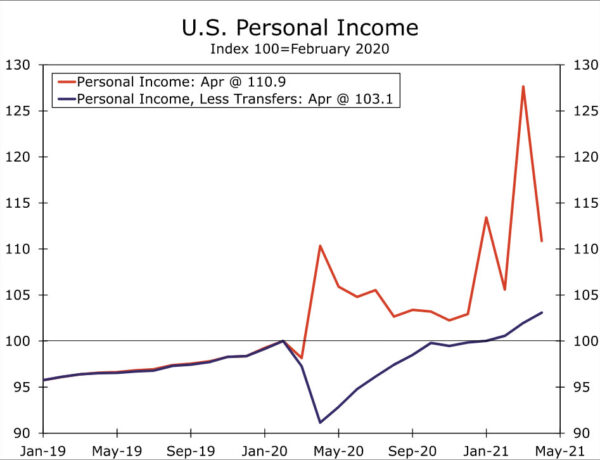

Despite Big Drop, Organic Income Growth Is Looking Good

The fact that personal income plunged 13.1% was due entirely to payback from stimulus-charged gains in March. Excluding transfer payments, personal income actually rose 1.1% during the month, and wages and salaries notched a strong 1.0% gain. In fact, wages and salaries have now posted 12 months of consecutive gains, driving the level 4.3% off of where it was prior to the pandemic in February 2020.

Had it not been for the drag from the stimulus checks going away, the takeaway would have been that personal income growth is really ramping up in a meaningful way and not just employment income. Proprietors’ income rose 3.2%, the fourth consecutive monthly gain, as shops get back to business. Rental income was 0.5% higher as well, and here too, this marked the fourth straight monthly increase. This report suggests that even as stimulus support is starting to fade, consumers have the ability to keep spending at a solid pace.

Just the Opening Bid on Reopening Spending

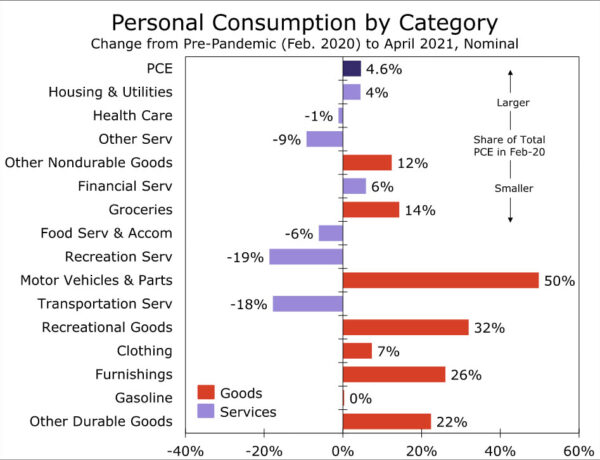

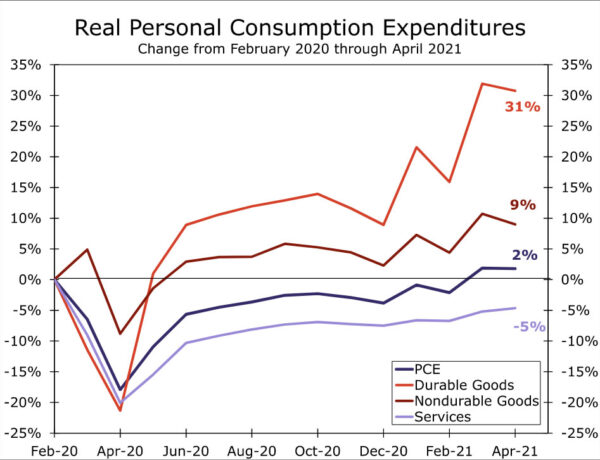

After a year of remarkably strong growth, we expect some soft patches in goods spending and that was evident in today’s report. Still, given the amount of money households hold in excess savings (about $2.4 trillion through April), we expect that goods spending will hold up, though a miss here and there should not come as a huge surprise given how much demand may have been pulled forward over the past year. Spending on durable goods actually eked out a 0.5% gain during April, led higher by a 4.1% pop in motor vehicle and parts purchases, the only major category of goods spending to rise during the month. Non-durable goods spending slipped 1.3%. But the declines across many goods categories in April barely make a dent in March’s increases.

Services spending increased during the month. Get used to hearing that. After service outlays have been suppressed for the past year or so, we look for major growth in this much larger share of consumer spending. While some non-discretionary categories of spending or “staples,” such as housing & utilities and financial services & insurance, have now exceeded their pre-pandemic levels (and healthcare is not far from it), “discretionary” and “other” services spending remain depressed but are poised for major growth in the months ahead. These categories are crucial to what we have deemed the “recreation renaissance.” The bottom line is: Consumers are flush with cash, and after more than a year of having few places to go, the flood gates are finally open.

It Costs How Much?

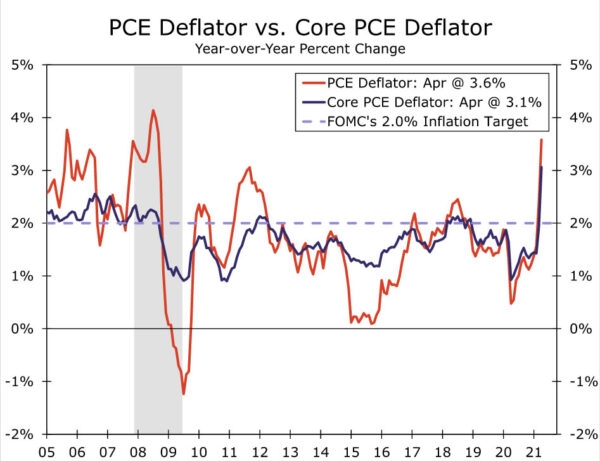

The gain in spending partly reflects higher inflation. The PCE deflator, which is the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation, rose 0.6 compared to March. The year-over-year rate jumped to 3.6% (see chart). Excluding food and energy, core prices rose 0.7%, pushing the year-over-year rate to 3.1%, the highest since the early 1990s.

Accounting for these increases in inflation, real personal spending decreased 0.1% last month, but spending was revised higher to 4.1% from 3.6% previously in March. Real goods spending declined 1.3% and services spending rose 0.6%.

While the steep year-ago comparisons are largely attributable to low base effects after the lockdowns last April weighed on activity and prices, inflation is heating up. The rapid resurgence in demand is being met with a dire level of supply, for both key physical inputs (like semiconductors) and labor. Businesses appear to be increasingly passing higher costs on, as indicated by April NFIB’s survey showing the largest share of firms raising prices since 1981. Although these recent price gains are undoubtedly associated with the reopening of the economy, they could prove lasting and have the potential to eat into consumers’ purchasing power.

As consumer prices continue to move higher and people return to long-neglected parts of the service sector, they are likely to experience “sticker shock” as they learn that many service providers have had to price-in the changes. Our best read is that worries about inflation could rattle confidence for a while, but the relatively healthy balance sheets of households and their desire to get out will outweigh the downside from higher prices on spending, at least for now.