We confirm our call that the RBA will extend its YCC policy to target the November 2024 signalling clearly that it does not expect to raise the cash rate before the end of 2024. This decision will be based on the Bank’s forecast timing of when it expects to attain its inflation; wages and full employment targets

This note draws on the Minutes to the March Board meeting; the Governor’s Statement (March 2) and his speech on March 10.

At the March Reserve Bank Board meeting, as expected, the Board maintained the policy settings which it had adopted at the February meeting and reaffirmed the conclusion in the Governor’s Statement:

‘The Board will not increase the cash rate until actual inflation is sustainably within the 2 to 3 per cent target range. For this to occur, wages growth will have to be materially higher than it is currently. This will require significant gains in employment and a return to a tight labour market. The Board does not expect these conditions to be met until 2024 at the earliest’.

This guidance was further emphasised in the Governor’s subsequent speech to the AFR Business Summit on March 10.

Markets are looking for some guidance around Yield Curve Control (YCC). In both the speech and the Statement, the Governor stated clearly that (speech) ‘the Bank remains committed to the 3-year yield target. We are not considering removing the target or changing the target from 10 basis points’.

However, he did restate that ‘The Board has not yet made a decision on this question (whether to keep the April 2024 bond as the target bond, or move to the next bond, the November 2024 bond) and will consider it again later in the year when it has more information about the economic recovery and the labour market’.

That is consistent with our ongoing view that any decision to extend the maturity of the target to November 2024 from April 2024 bonds will be determined by the Bank’s forecasts of the timing of the achievement of their inflation; wages and full employment objectives.

That decision is likely to be deferred until the August Statement on Monetary Policy, although with the Bank already owning up to 60% of the existing April 2024 bond, an earlier decision may be necessary as markets remain restive.

At the August SOMP the Bank will extend its forecast horizon to the end of 2023.

Limiting the YCC to the April bond implies that the Bank gives a reasonable chance to achieving its conditions for the first rate hike by the first half of 2024.

The current end point of the most recent forecasts (February SOMP) is mid- 2023. Wages growth is forecast to reach 2%; underlying inflation 1.75%; and the unemployment rate 5.25%.

(The RBA was not expecting the 0.6% lift in wages growth in the December quarter with annual wage inflation for 2020 forecast in the February SOMP at 1.25% compared to the actual of 1.4%. That probably lifts the 2% (mid 2023) forecast to 2.25%.)

By the time of the August Statement the RBA will have received one update on the Wages Index; two updates on the CPI; and the last employment report will be for June.

Over that period there is likely to be some ‘noise’ in the data. The annual CPI will be affected by the base effects from COVID; while wages and particularly employment will be impacted by the unwinding of JobKeeper at the end of March.

The Minutes of the March Board meeting noted that ‘there may be a temporary pause in the pace of improvement in the labour market … as businesses adjust to the tapering of some fiscal support measures’.

For example, there are likely to be many businesses that qualified for JobKeeper assistance in the March quarter (with a 30% reduction in quarterly revenue in the December quarter relative to December 2019) which have been able to retain their full staff complement due to the subsidy from JobKeeper. Once that subsidy disappears it may be necessary for businesses to shed those workers whose marginal contribution to revenue falls short of their cost.

On the other hand the RBA reports in the Minutes that many firms in receipt of the JobKeeper subsidy had already reduced the size of their workforces (therefore receiving a lower subsidy) and were not planning any further lay-offs.

The RBA’s own current forecasts envisage a lift in headline inflation to 3% in the June quarter while the unemployment rate is only expected to fall by 0.3% between December and June 2021.

So, it seems reasonably unlikely that the RBA will see data over the next four months or so that would give it grounds for substantially lifting the current end point forecasts (mid 2023) to levels by end 2023 that would be consistent with the expectation that the conditions for the first rate increase will be reached by the first half of 2024.

Accordingly, our current assessment remains that the Bank’s forecasts in the August SOMP will be consistent with an extension of YCC to the November 2024 bond.

The Minutes to the March Board meeting also pointed out that if the Board does move to the November bond ‘it would not consider removing the target completely or changing the target yield of 10 basis points’ – indicating that an extension to November would still mean a 10 basis point target on April (although this is likely to be a largely academic exercise as RBA would own most of the April’s by then).

We do note that market pricing continues to be opposed to our view that the Board will shift YCC to the November bond at 0.1% after the August SOMP.

Decisions are likely to come down to a value judgement between maintaining the Bank’s credibility and settling bond markets.

I believe the Governor’s speech last week was firmly aimed boosting the Bank’s credibility.

Indeed, it may be the time for the RBA to challenge markets with a clear message that it intends to defend its credibility by making decisions which are consistent with its forecasts.

The key forecast ‘updates’ in the speech had something for both sides of the argument.

In earlier speeches there has been some reference that the target level of wages growth that would be consistent with inflation ‘sustainably within the 2–3% target band’ was around 3.5% (using the 1% productivity growth rule of thumb).

However, in the latest speech the Governor has now settled on ‘wages growth sustainably above 3%’ or ‘running at 3% plus’.

That reduces the wages growth ‘hurdle’ for the rate hike.

However, in the same speech, he noted ‘it is certainly possible that Australia can achieve and sustain an unemployment rate in the low 4’s’. The wages and prices data will help signal how close the economy has come to that full employment target.

If the RBA believes that a ‘low 4’s’ is the appropriate level for the unemployment rate to achieve the inflation and wages targets then the challenge to achieve those objectives by 2024 H1 is significant.

But how will the RBA and other central banks respond to the recent signals from the bond market?

Credibility and patience are going to be the catch cry for central banks globally.

It is my view that central banks will no longer be held to account by bond markets.

The fear of ‘being behind the curve’ will not dominate central bank thinking as it has in past policy cycles.

The need to be pre-emptive for fear of inflation overshooting and economies ‘over heating’ has been rejected.

After years of under performing on inflation and wages objectives central banks will be prepared to ‘risk’ the wrath of the markets.

In turn, the markets are well advised not to overlook the rule ‘don’t fight the FED’ – central banks have adequate fire power to stare down markets if they desire.

The information content in bond rates should only become disturbing to central banks if the inflation component of nominal bond rates significantly exceeds their targets, (in the case of Australia, 2–3%).

Although bond rates have increased recently at a faster pace than we envisaged when we lifted our forecast for AUD 10 year rates by end 2021 from 1.55% to 1.9% and US rates from 1.5% to 1.8% (back on February 19) most of the recent adjustment has been to move real rates further towards zero from deeply negative territory.

The current inflation component of bond rates is closely in line with the RBA’s and FED’s targets. Restoring inflationary expectations to more realistic levels should be a source of satisfaction to central banks. The concern would come, particularly for the FED, if the inflation component significantly exceeded the target.

It is our expectation that as the bond rate rises (we have targets of around 3% for both Australia and US by 2023/24) the adjustment will largely be reflected in higher real rates signalling confidence that growth prospects will improve – without indicating any damaging overshoot in inflation or inflationary expectations.

The recent signals should be encouraging to central banks indicating that markets are embracing improving growth prospects which may begin to absorb the current slack in labour markets but not indicating the need to lean against the recovery.

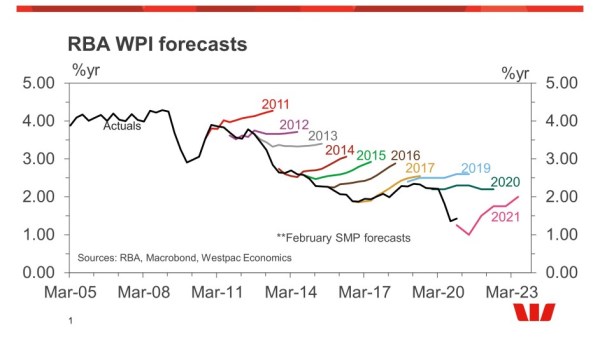

Rising bond rates and some uncertainty in the short end of the bond market should not deter the RBA from the objective of reaching their inflation; wages; and employment targets and restoring policy credibility after years of consistently missing their targets, (see slide for evidence of RBA’s consistent overshooting of wages forecasts).

For Australia, a period of very low official rates will always risk financial instability in the housing market.

The RBA Governor, with good reason, currently sounds relaxed. The emphasis is on housing credit growth where he notes, ‘investor and business credit growth remain weak.’ But the warning that ‘Lending standards remain sound and it is important that they remain so.’ is an addition to earlier statements and really summarises the Board’s approach to the current housing boom.

In his speech the Governor further stressed that point: ‘There are various tools, other than higher interest rates, to address these concerns, leaving monetary policy to maintain its strong focus on the recovery in the economy, jobs and wages’.

The RBA has successfully slowed housing markets in both 2015 and 2017 using these ‘various tools’ without needing to raise rates. It seems reasonable that another round of such policies can be expected sometime in 2022 but the authorities will need to be careful not to be too heavy handed.

A repeat of the experience of 2018–2019 when Sydney (–15%) ad Melbourne (–11%) dwelling prices deteriorated sharply with the unintended consequence of slowing the economy overall will need to be avoided.

Conclusion

Markets are convinced that the RBA will not extend its Yield Curve Control (YCC) policy beyond the April 2024 bond.

Our analysis of the Bank’s current forecasts and prospects for any revisions out to the August SOMP indicate that to maintain credibility, and consistent with its forecasts, the Bank will decide to extend the YCC policy to the November 2024 bond