Executive Summary

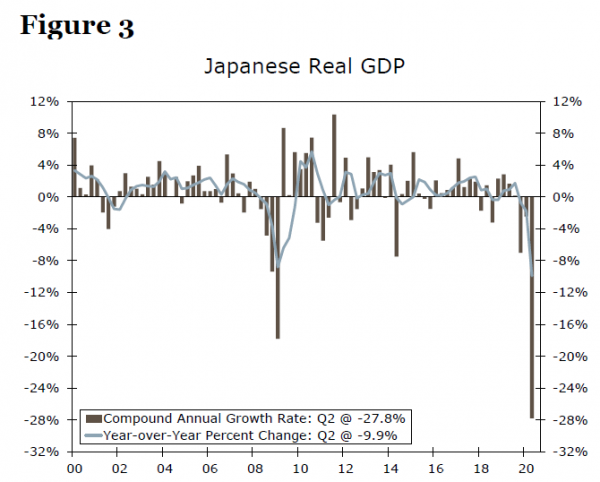

Although Japan appears to have more successfully contained the spread of COVID-19 compared to many other major developed countries, Japan’s economy still struggled mightily in the first half of 2020. Real GDP was down 9.9% year-over-year in Q2, a bit more than the 9.5% contraction in the United States, but still less than the 15.0% collapse in the Eurozone. Higher frequency economic data suggest a rebound began to take hold towards the end of the second quarter. Like households in the United States, Japanese households have seen their incomes lifted in the aggregate by government transfer payments, which has helped to offset the decline in other sources of personal income. In the near-term, we believe this firepower can spur a boost to economic growth. But over the medium- to longer-run, the recovery will need to be more self-sustaining, something the Japanese economy has struggled to achieve in the past, particularly if external demand is weak. Our forecast for the Japanese economy has real GDP still roughly 4% lower at the end of 2021 than it was at the end of 2019. While we believe the risks to this forecast are skewed to the upside, the sizable hole signals just how long we think it will take to close the output gap in Japan.

Japan’s Economy Looks to Bounce Back in the Second Half of 2020

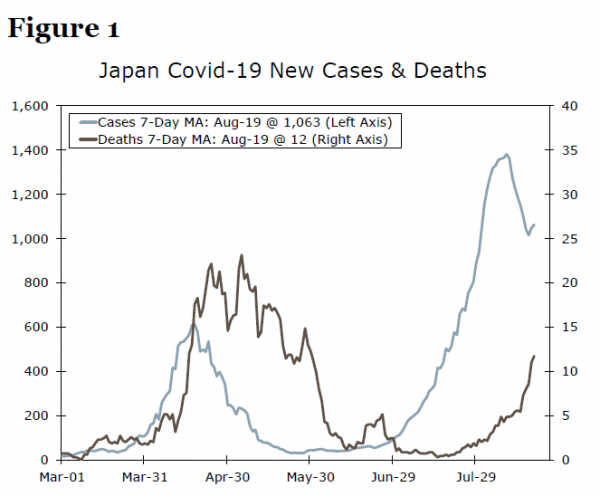

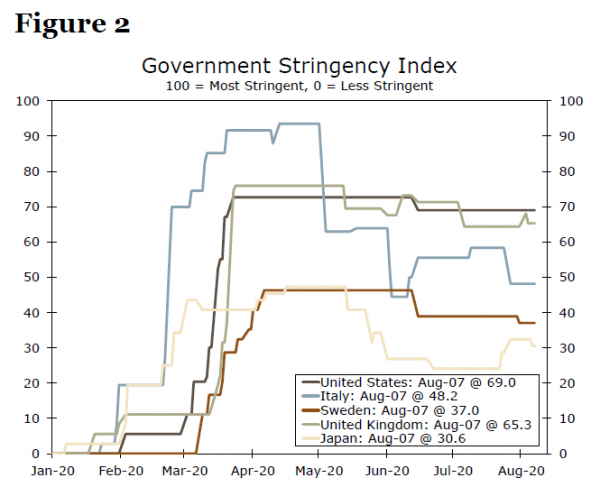

New COVID-19 cases in Japan peaked around 600 per day on a weekly average basis in April (Figure 1), a much lower level than in most of Europe or the United States. As April turned to May and June, new cases steadily receded such that the outbreak appeared largely under control. Around July 1, cases began to accelerate again, with deaths not too far behind. But new cases appear to have topped out once again, and on a relative basis COVID-19 has wrought a far lower human toll on Japan than in most of Europe or the United States. Japan has a total of just nine deaths per million people, in comparison to 523 per million in the United States or 586 per million in Italy. With a less serious public health situation, policymakers in Japan have generally adopted less stringent limitations on mobility and private activity (Figure 2).

Despite a less severe lockdown, the Japanese economy has taken a nosedive like many of its developed market peers. Data on Q2 real GDP growth in Japan showed a 27.8% annualized contraction (Figure 3). Although the quarterly declines in real GDP in Japan in the first half of 2020 were not as big as they were in the United States or the Eurozone, this comes with a caveat: the H1-2020 contraction in Japan comes on the heels of a 7% annualized contraction in Q4-2019 due to an increase in the country’s consumption tax. On a year-over-year basis, real GDP was down 9.9% in Q2-2020, a bit more than the 9.5% contraction in the United States, but still less than the 15.0% collapse in the Eurozone.

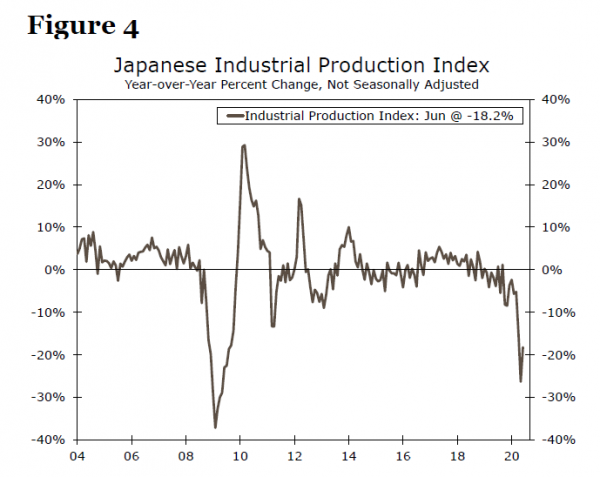

Japanese economic data with a monthly frequency suggest a rebound began to take hold towards the end of the second quarter. Retail sales surged 13.1% in June and are now “only” down 1.2% year-over- year (for comparison, U.S. retail sales increased 2.3% year-over-year in June). Japanese industrial output rose in the month of June for the first time since January, and if May marks the bottom in factory sector output the year-over-year decline would actually be less severe than it was at the bottom of the Great Recession (Figure 4). Nonetheless, industrial activity still appears to have some way to go before fully recouping its COVID-induced declines. On the labor market front, employment was down just 1% in June, a far cry from the 8.6% contraction in the United States over the same period. That said, PMI readings for the manufacturing and service sectors were both in the mid-40s in July, and the job-to-applicant ratio fell in June for the sixth consecutive month, a sign that workers looking for jobs may be facing increased competition amid a weakening labor market.

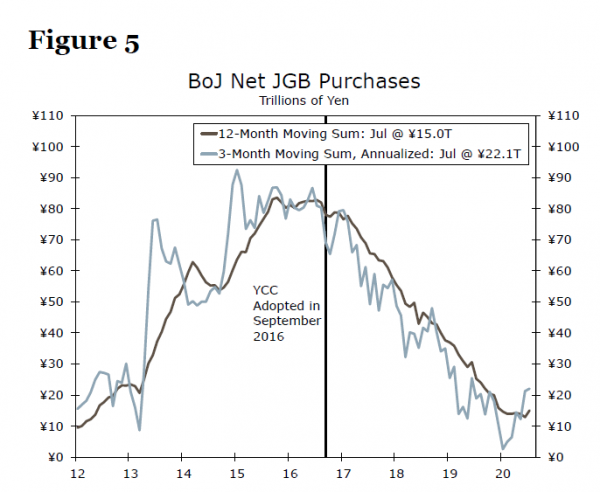

At the monetary policy level, the stimulus offered by the Bank of Japan (BoJ) has been much less decisive than that implemented by other major central banks. This is due in large part to the hypereasy monetary policy that prevailed before COVID-19. In the first couple months of the pandemic, the BoJ did adopt some new, stimulative measures, such as doubling its ETF purchase target to ¥12T and increasing the purchase target for commercial paper and corporate bonds to ¥20T. Similar to the Federal Reserve and others, the BoJ has also implemented numerous liquidity-providing measures to ensure the flow of credit remains robust. But at recent meetings, the BoJ has largely kept key policy levers (for example, policy interest rates or asset purchases) unchanged. BoJ purchases of sovereign bonds have ticked up a bit (Figure 5), but market forces have kept the 10-year government bond yield tethered near the central bank’s target of 0% such that a significant increase in purchases has not been necessary.

On the fiscal front, policymakers have done much more heavy lifting, and we believe this should provide a lift to economic growth in the near-term. The International Monetary Fund estimates that Japanese direct fiscal support through additional spending and foregone revenue amounts to 11.3% of GDP, one of the highest in the G20. Support to businesses in the form of both direct and indirect support appears to have helped at least somewhat; business fixed investment “only” declined 1.5% on a non-annualized basis in Q2, and the average number of business bankruptcy cases with total debt of 10 million debt or more was basically flat through the first seven months of 2020 compared to the same period in 2019. While we do not yet have complete data on household disposable income, based off the partial figures we do have, we believe household disposable income was probably at least flat, and may have risen as much as 10%, compared to Q1.

Like households in the United States, Japanese households have seen their incomes lifted in the aggregate by government transfer payments, which has helped to offset the decline in labor compensation, rental income and other sources of personal income. In the near-term, we believe this firepower can spur a boost to personal consumption and economic growth. Over the medium-term, however, many households that have seen their incomes reinforced by fiscal policy measures will be asking themselves whether this support is just a temporary boost in the face of a more permanent decline. Being flush with cash is certainly a reason to be optimistic about one’s current economic situation, but if this cash will eventually run out, with few prospects for fully replenishing it, the medium-term outlook for personal consumption will not be as strong. To that point, Japanese consumer confidence in July stood at 30.4, still well below its reading of 38.4 in February, and household assessments’ of their expected income growth over the next six months have fallen significantly over the same period. Overall, however, recent developments do suggest potential for growth to surprise to the upside for the next quarter or two. Our base case currently projects GDP to grow at an annualized rate of 8.2% in the third quarter and for GDP to contract by 5.5% for fullyear 2020. However, we see the risks tilted towards faster growth in Q3 and a smaller fall for calendar 2020.

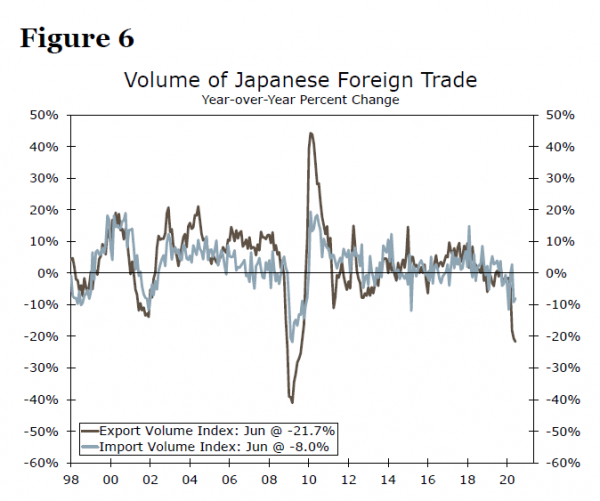

Another key factor related to the medium-term outlook will be the recovery in external demand. Exports comprise about 19% of Japanese GDP, and they have plummeted over the past several months (Figure 6). Real exports of goods and services declined 18.5% on a non-annualized basis in Q2, a contraction that came on the heels of a 5.4% decline in Q1. Removing international trade from the equation, Japanese real GDP would have only fallen 6.9% year-over-year in Q2, compared to the actual decline of 9.9%. Unlike the domestic sector of the economy, there is little Japanese fiscal and monetary policymakers can do to rectify the weak external sector, and as such this sector’s fortunes will be largely tied to the public health and economic policy outcomes in the rest of the world. Overall, while we see solid reasons, fundamentally and mechanically, for a sharp jump in sequential Japanese economic growth in Q3 and to a lesser extent Q4, the medium-term prospects remain less promising. That is especially the case given several historical precedents over the past few decades where large-scale fiscal stimulus in Japan has failed to generate a self-sustaining recovery that keeps Japan’s economy close to or above its potential growth rate for an extended period. Our forecast for the Japanese economy has real GDP still roughly 4% lower at the end of 2021 than it was at the end of 2019. While we believe the risks to this forecast are skewed to the upside, the sizable hole signals just how long we think it will take to close the output gap in Japan.