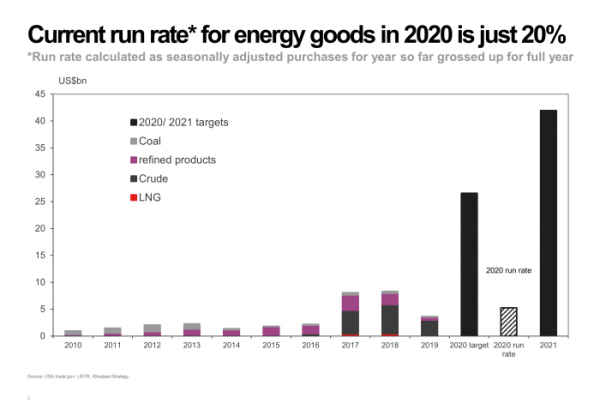

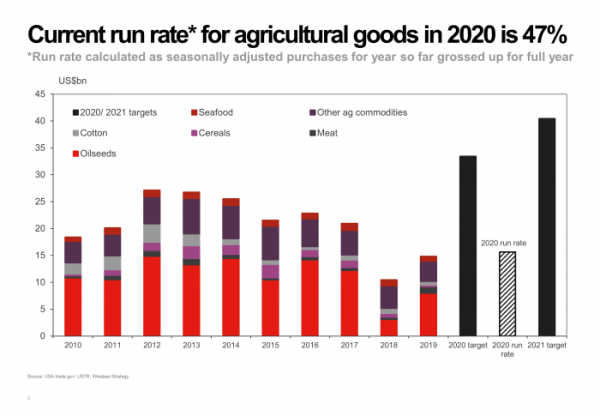

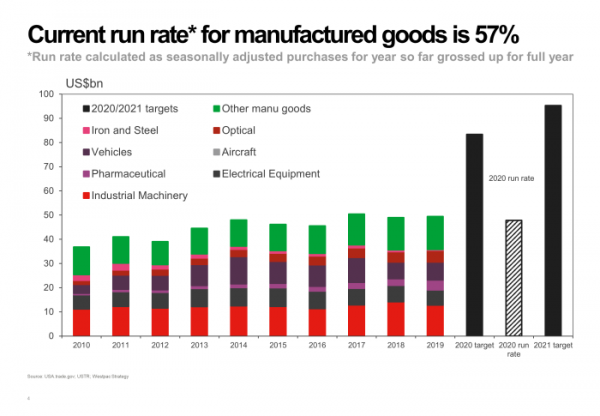

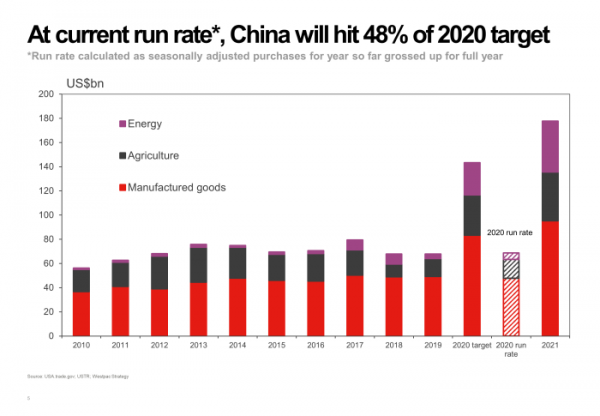

At the 2020 half way mark, China is on a run rate to meet just 20% of its energy product obligations; 47% of agricultural and 57% of manufactured goods purchases for a total of 48% of its overall 2020 targets under the terms of the Phase One Trade Agreement. So does that constitute a fail?

Is That a Fail?

We have maintained an increasingly sceptical view on whether it was ever possible for China to meet it’s purchase obligations under the phase one trade agreement – (see Can China actually buy US$50bn of US energy products?; So how is that phase one deal going? and US China Trade Agreement Update – Not Impossible?)

As of the end of June, despite a sharp increase in energy purchases in May and June, China is set to meet just 20% of its energy product obligations under the terms of the Phase One Trade Agreement. Indeed, to meet the agreement, it would have to step up its purchases by a factor of 9 times the average purchase in the first six months of the year, and buy that amount in every month through to the end of 2020.

As of the end of June, China is on track to meet 47% of the agreed 2020 agricultural purchases. To meet its agricultural product purchase obligations under the terms of the Phase One Trade Agreement, it would need to increase the average imports in the first half of 2020 by a factor of slightly more than 3, and continue at that pace through the rest of the year.

For the manufacturing goods captured in the phase one trade agreement, China is currently on track to meet 57% of its obligations. To meet those objectives, China will need to double the average seasonally adjusted run rate for the year so far for manufactured goods and maintain that through each month of the year.

This then means that China is currently on a run rate that will see it meet just 48% of its overall 2020 target under the phase one trade agreement for 2020.

Now as we noted last month, the phase trade agreement is not just about numerical targets. Indeed, trade expansion is just one chapter within a complex process which includes agreements on:

- Intellectual property including sections on protecting trade secrets and confidential business information

- Technology transfer including sections on scientific and technological cooperation

- Trade in food and agricultural products including sections on accepting USDA and FDA audits and standards

- Financial services including sections on opening up banking services, credit rating services, electronic payment services, insurance, securities, fund management and futures services within agreed periods of time.

- Exchange rate practices designed to avoid “manipulating exchange rates … to gain an unfair competitive advantage”.

- Expanding trade including a “commitment that purchases and imports into China will be no less than $32.9bn above the corresponding 2017 baseline amount” for specified manufactured goods; “$12.5bn above the corresponding 2017 baseline amount” for agricultural goods and “$18.5 billion above the corresponding 2017 baseline amount” for energy products.

So, it is clear that numerical trade expansion obligations are not the only measure of whether China is meeting its agreed objectives. However, these measures are finite and can be observed, tracked and measured. And they should be.

At the upcoming mid-year review, both the US and Chinese administration should recognise that it is simply not going to be possible for China to meet its 2020 obligations. Indeed, on the current seasonally adjusted run rate, China will not even hit the 2017 baseline let alone the increase required over 2017 levels to meet the agreement for 2020.

To be sure, the agreement does not stipulate any milestones that need to be reached and when; so it is not clear that anything other than a ‘room for significant improvement’ need be issued next week. However, with each passing month it is increasingly looking like a fail, meaning discussions must start to turn to how to deal with a revision, to limit the risks of a collapse.