Recent U.S. dollar weakness is less pronounced when measured against the currencies of U.S. trading partners. The outlook for trade, and to a lesser extent inflation, relies more on demand at home and abroad.

‘Cause Everything Around Me is Falling Down

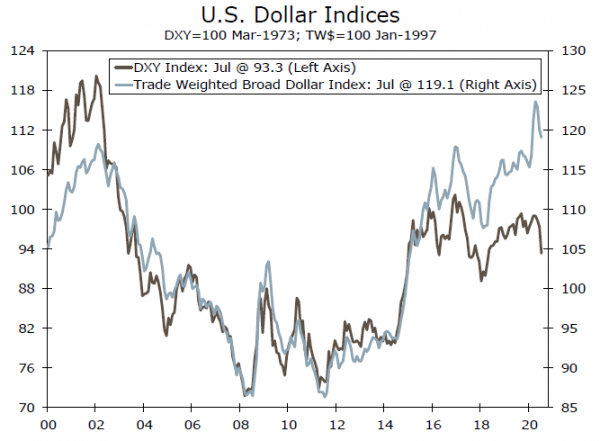

The U.S. dollar has weakened in recent weeks, with the dollar spot index now down around 4% over the past month, the most recent down-leg of a weakening trend that has seen this measure of the greenback fall almost 10% since March to roughly its lowest level in the past two years. While markets rely on dollar spot, or the DXY index, which is a reflection of FX markets globally, many economists follow measures that reflect trade flows like the Fed’s trade-weighted broad dollar index (TW$). As the name implies, this measure more accurately reflects the dollars’ eventual impact on imports and exports. The key difference between the two indices comes down to their weighing of currencies. The euro accounts for more than 50% of the DXY index, which only includes five other currencies (the pound, yen, Canadian dollar, krona and Swiss franc). The TW$, however, gives a more considerable weight to 26 currencies each based on their volume of bilateral trade. The currencies used make up over 90% of U.S. trade. The euro still has the largest weight, but at just 19% versus 58% in the DXY index.

While the two indices typically move together (top chart), they can differ based on what is driving dollar weakness, as is one of many factors today with the euro being a particular standout, gaining more than 10% versus the dollar since mid-March. From its March peak, the TW$ is off just 7% versus the more-sizeable 10% decline in the DXY index.

It is not too difficult to explain recent dollar weakness. Not only has the Fed provided massive liquidity to financial markets, but other central banks and foreign governments have now caught up with stimulative policy—most notably the European recovery fund plan. Further, the turning of the tables between the U.S. and Eurozone in terms of re-accelerating case counts also has likely played a role. These are just a few factors behind recent dollar weakness, which has raised concern of what further depreciation means for the economy more generally.

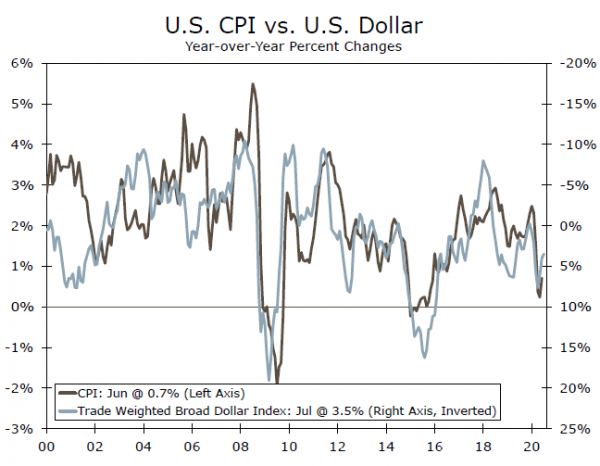

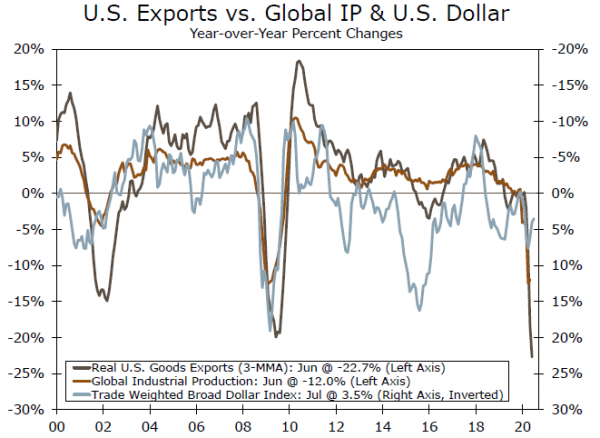

In theory, and holding other factors constant, a weak dollar should make exports less expensive to foreigners and imports more expensive to U.S. buyers, and could result in higher inflation. Dollar depreciation should help exports at the margin, but growth in the rest of the world is a much larger influence on U.S. export growth (middle chart). If, as we expect, the global economy begins to recover, export growth should pick up with a weaker dollar providing some extra wind in the sails. In terms of imports, the effect is a bit trickier to decipher today. Total domestic demand began to recover in May and June and we expect that recovery continued into Q3. Imports are likely to rise as domestic demand increases, even despite a weaker dollar providing a modest headwind. Recent history shows a weaker dollar does not always lead to higher price growth. Take 2002-2008 for example, there was sustained dollar weakness but that period actually saw inflation below 3% on average (bottom chart).