U.S. Review

The Risk of a Second Wave

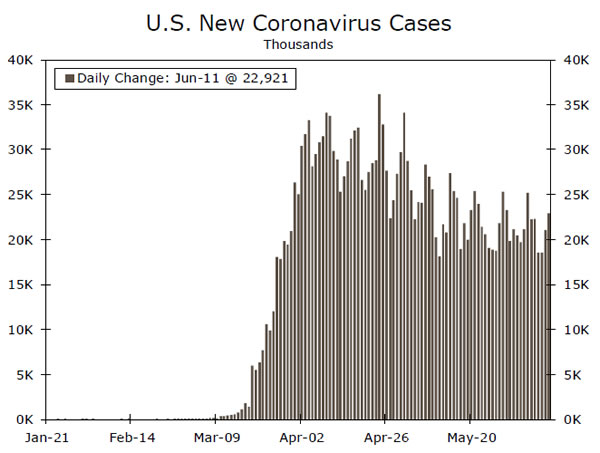

- Lockdowns began to be lifted across most of the country by the end of May and the total amount of daily new coronavirus cases has been trending lower. But the flattening case count has not been consistent across the country.

- Re-opening the economy without a vaccine always entailed the risk of a second wave, which is the largest risk to a steady economic recovery.

- While we are monitoring this serious risk, we continue to expect the gradual re-opening of the economy to result in a measured rebound in activity.

The Risk of a Second Wave

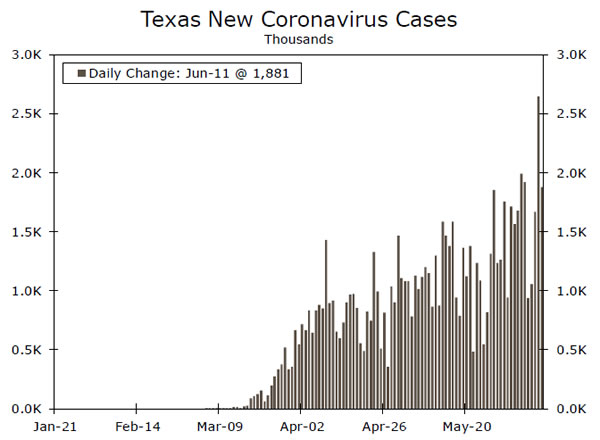

Lockdowns began to be lifted across most of the country by the end of May and the total amount of daily new U.S. coronavirus infections has been trending lower. But the flattening case count has not been consistent across the country. While the U.S. as a whole saw the slowest pace of new case growth since March on Tuesday, it was the very next day that Texas reported its highest one-day total of new cases since the pandemic began. This uptick in case growth has raised concern of a new wave of lockdowns.

Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin has said the U.S. cannot have another lockdown, but it is possible for local governments to reimpose stay-at-home orders. Even without official government instruction, a second wave could curb spending if households pull back from the economy out of fear.

But the country is arguably better prepared for a second wave. Testing is more widely available, people have access to protective gear such as masks and awareness of the virus is just generally higher than it was at the onset of the pandemic. Preparedness itself could therefore obviate the need for large portions of the country to re-enter a state of lockdown.

All told the re-opening of the economy without a vaccine always presented the obvious risk of a second wave, which is by far the largest risk to a steady economic recovery. While we are monitoring this risk, we continue to expect the gradual re-opening of the economy will result in a rebound in activity.

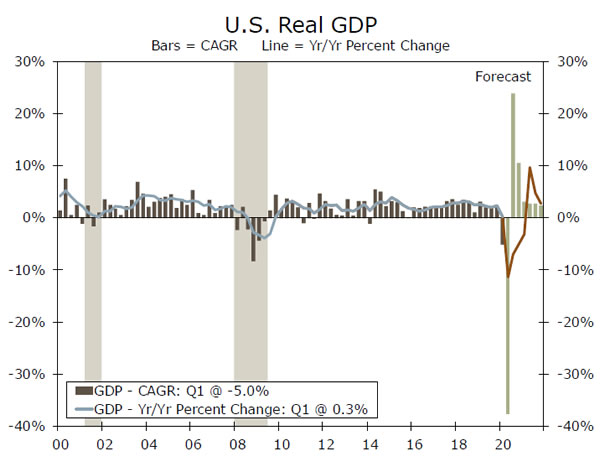

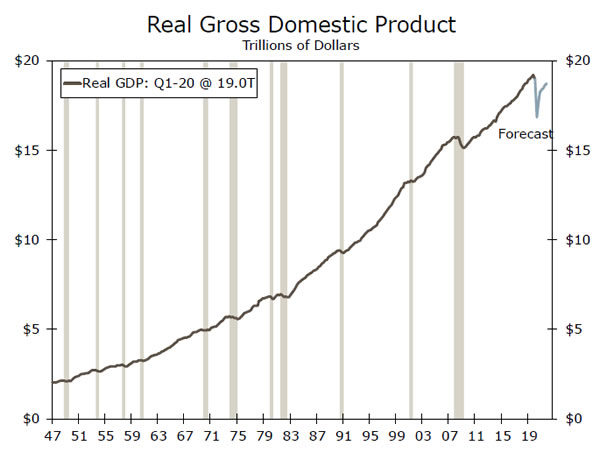

In our latest forecast, we downwardly revised our Q2 GDP growth estimate, to a nearly 40% annualized pace of decline but upwardly revised our Q3 estimate on our expectation for a pronounced rebound. Still, the road to recovery will be long. By the end of this year, the U.S. economy will be about 5% smaller than it was at the end of 2019 on a real basis, and even by the end of 2021, we expect the level of real GDP will still be about 2.5% shy of the prerecession peak.

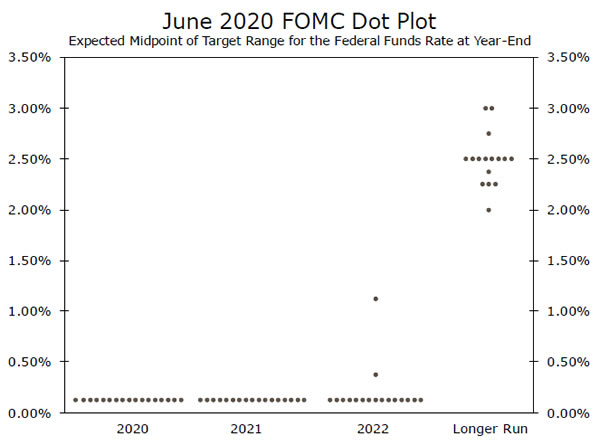

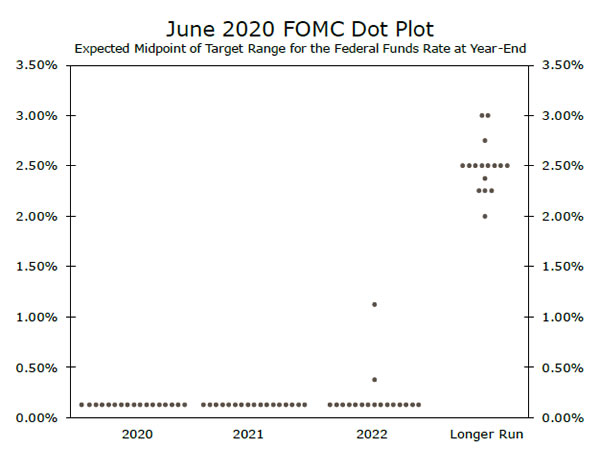

The June Summary of Economic Projections released at this week’s FOMC meeting reveled the participants’ similarly grim growth outlooks. When Powell was pressed further during the post-meeting press conference regarding how the Fed would react if things turned out better than expected, he responded with “we’re not even thinking about thinking about raising rates.” This forward guidance was echoed in the FOMC “dot plot,” which showed most participants believed the Fed would keep the fed funds rate at the zero lower bound through at least 2022. More broadly, Powell reiterated the Fed’s dedication to supporting the economy through the crisis and its willingness to adjust policy as needed. He also stressed that while the outlook remains highly uncertain the committee thinks it is going to be a gradual recovery.

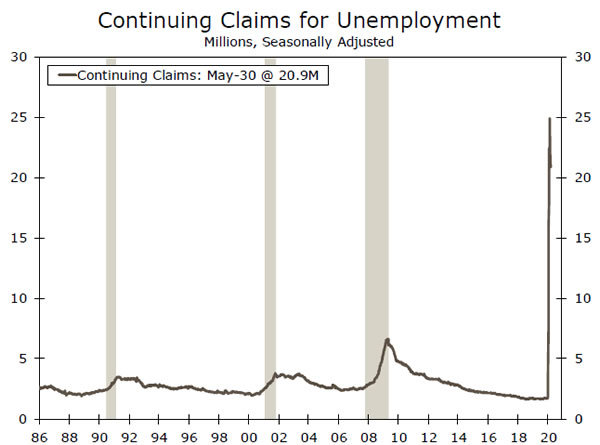

Data this week continued to suggest just that. The number of initial filers for unemployment insurance last week was the lowest it has been since March, but it was still well-north of one million, and while continuing claims have come down over 20 million people remain out of work. In terms of inflation, consumer prices fell for the third consecutive month in May, as retailers grappled with the plunge in consumer demand. But with a pick-up in activity, we don’t expect core consumer inflation to fall further.

The road to recovery will be long, and a second wave of the virus will only make it longer.

U.S. Outlook

Retail Sales • Tuesday

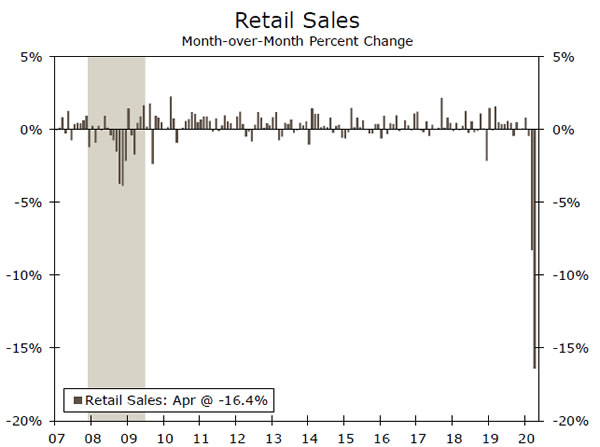

We expect retail sales surged 6.7% in May, but that is not to say that consumer spending is anywhere close to where it was prior to the virus. First, we are coming off an extremely low base—sales were around $525 billion on an annual basis, before falling to $483 billion in March and then plunging the most on record to just $404 billion in April. With the majority of the country somewhat ‘re-opened’ by the end of May, it would be hard not to see a large bounceback.

Second, incomes soared in April, despite more than 20 million job losses. This was the direct result—and explicit goal—of the CARES Act. The economic impact payments and augmented unemployment insurance combined to boost personal income 10.5%, more than cushioning the blow from job losses. Yet personal spending fell 13.6%, driving the saving rate all the way up to 33%. Some of this should unwind in May, boosting retail sales.

Previous: -16.4% Wells Fargo: 6.7% Consensus: 7.4% (Month-over-Month)

Housing Starts • Wednesday

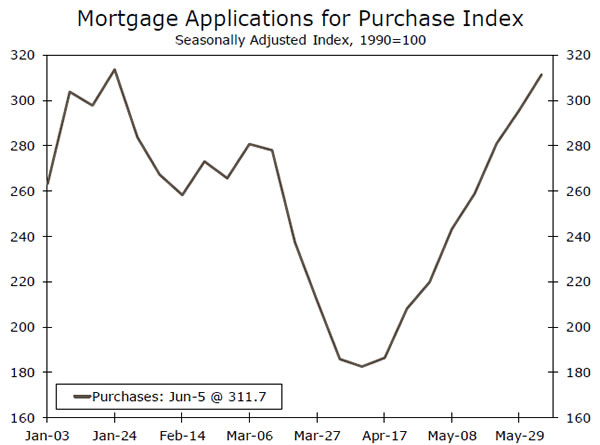

Housing looks to be the strongest sector of the coronavirus economy. Mortgage purchase applications have more than completed a ‘V-shaped’ recovery, unlike any other major indicator we are aware of (the NASDAQ notwithstanding). Robust demand for housing, driven by record low mortgage rates and pent-up Millennial demand, are great signs for home sales and, eventually, new home construction. We are carefully watching the split between singlefamily and multifamily starts, however, given the disproportionately large job losses among renters, relative to prospective homebuyers.

More broadly, housing has historically provided a large cyclical boost to economic recoveries, driving demand for appliances, furniture, building materials and a host of services, such as insurance, mortgage servicers, inspections, interior designers and landscapers. We expect to see a fairly significant impulse to growth from housing, beginning with a rebound in housing starts in May to 1,137K.

Previous: 891K Wells Fargo: 1,137K Consensus: 1,100K (SAAR)

Jobless Claims • Thursday

Overreliance on jobless claims led every forecaster to miss the increase in May nonfarm employment, but claims are still a useful indicator. Initial claims the week ended June 6 fell 19% from the prior week to 1.5M, the largest percentage decrease since April 11. Continuing claims the week ended May 30 fell by 340K t0 20.9M, only the second decrease since the crisis began. The decrease would have been larger if not for outsized increases in California, Florida and Oregon. But both of these numbers are still horrific.

Adding in the nearly 10M people receiving PUA benefits, there are more than 30M Americans receiving UI insurance. It’s therefore hard to get too optimistic about the May nonfarm surprise. Moreover, for the first time we know of, the insured unemployment rate is higher than the U3 unemployment rate. Three reasons: (1) BLS admits it misclassified people, (2) labor force exits and (3) generous UI benefits causing a higher proportion to file claims.

Previous: 1.5M, 20.9M Consensus: 1.3M Initial, 19.8M Continuing

Global Review

COVID-19 Curve Flattening, but Not Everywhere

- This week, activity and sentiment data flow were relatively thin, with COVID-19 still dominating headlines and influencing the path of financial assets. Cases at the global level continue to rise, albeit at a slower pace, while Latin American countries have been unable to flatten the curve.

- In that context, concerns over a second wave of infections weighed on financial markets and risk assets, in particular equities and foreign currencies. Emerging currencies sold off sharply toward the end of the week, while international equities relinquished some of the gains of the past month or so.

Renewed Coronavirus Concerns Hit Financial Markets

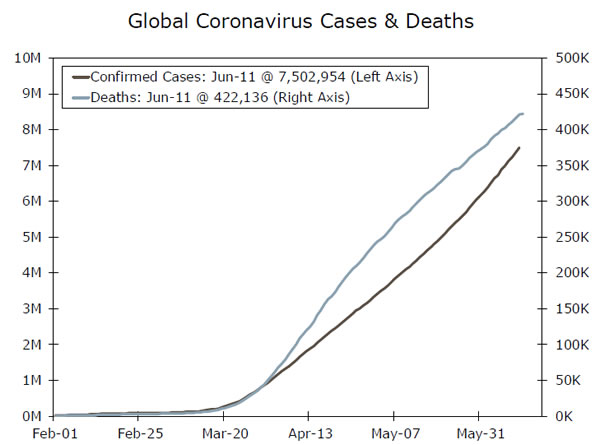

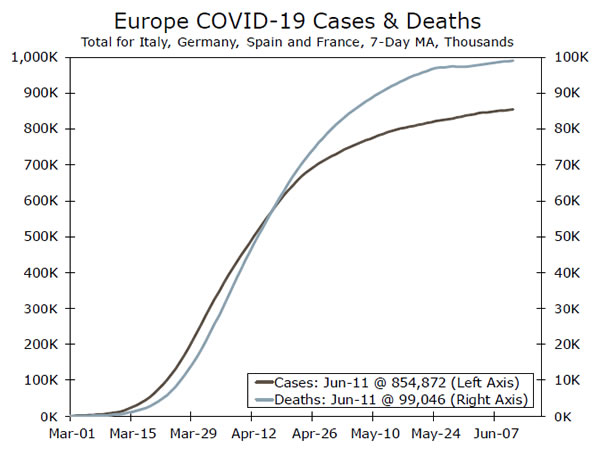

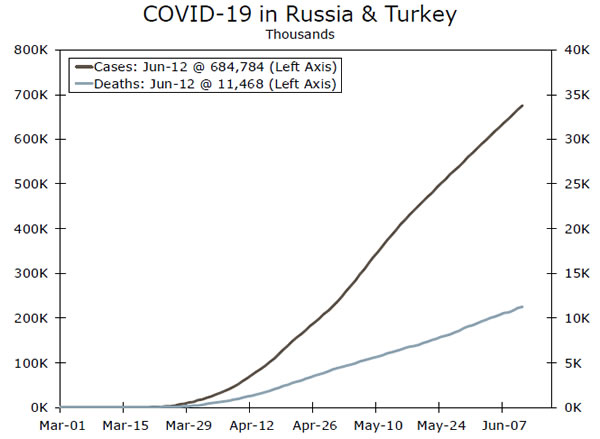

COVID-19 continues to dominate headlines. In fact, new concerns regarding the possibility of a second wave of infections in parts of the United States contributed to a sharp selloff in financial markets around the world toward the end of this week. As of mid- June, global cases were over 7M, while over 420,000 fatalities have been recorded. While global confirmed cases continue to increase, the overall pace of infection growths has started to slow. This has been most evident in Europe—in particular in Italy, Spain and France—which previously were virus hot spots. A slower pace of infections has also been seen in some of the larger emerging markets throughout Europe as well. Russia, as of now the third most infected country, has shown signs of containing the virus, while Turkey has also seen the confirmed cases curve begin to flatten.

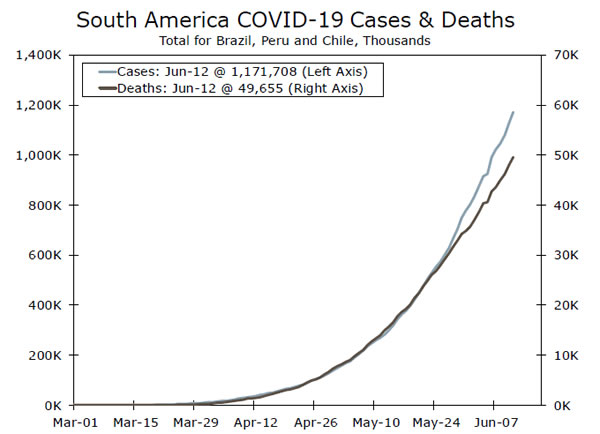

While Europe has made progress and is leading the charge on virus containment, other parts of the world have been less successful. In particular, South America has become the new epicenter, with essentially none of the major Latin American countries able to manage the spread of the virus. Brazil is now the second most infected country in the world, while Peru, Mexico and Colombia have seen infection rates continue to rise with no evidence of the curve flattening. Lockdown measures have been in place in most South American countries; however, compliance with these rules has been less than adequate and has contributed to the dramatic increase in confirmed cases. Moreover, government officials, specifically in Brazil and Mexico, have pushed back against social distancing measures, which has led to poor compliance with lockdown measures and confirmed cases continuing to rise. The United States has seen some progress, but recent data signal a second wave of infections is still possible and has raised concerns around another wave of infections globally.

In response to these concerns and a renewed wave of infection’s potential damage to the global economy, financial markets sold off quite sharply this week, especially toward the end of the week. Asset prices across Europe declined, with equities and foreign currencies coming under the most pressure. Just this week, the MSCI EAFE equity index sold-off more than 3.5%, while currencies such as the euro and British pound weakened. Emerging markets asset prices came under the most pressure as the MSCI emerging markets equity index declined around 1.5% and currencies across the emerging markets spectrum weakened. As of now, we are not building a second wave of infections or another significant economic shock into our forecasts and would need to see more evidence before adopting this assumption. However, we acknowledge the possibility of a second wave of confirmed cases not just in the United States, but globally, and it is something we will be keeping a close watch on going forward. Should new virus cases increase significantly, it is possible we may have to adjust our GDP and inflation expectations in many foreign economies.

Global Outlook

Brazilian Central Bank • Wednesday

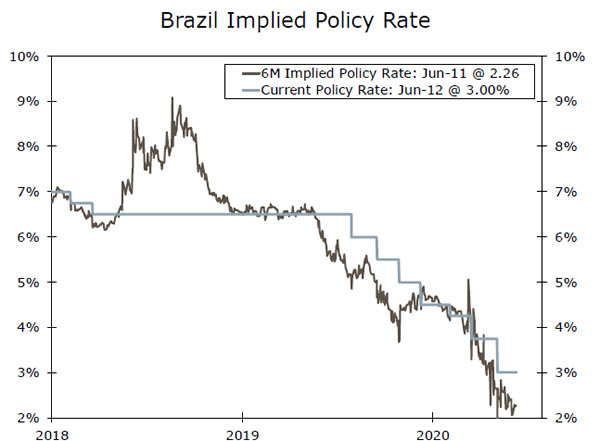

As COVID-19 continues to spread throughout Brazil, the domestic economy has come under significant pressure. Economic activity has essentially ground to a halt, while growth and inflation expectations in Brazil have fallen notably. In response, the Brazilian Central Bank has lowered its Selic rate quite aggressively over the course of this year, cutting rates 150 bps to 3.00%. This year’s policy rate cuts come in addition to 200 bps of cuts delivered last year, and currently place the Selic rate at its lowest point on record. Next week, the central bank will meet again to assess monetary policy, and in our view, will cut interest rates and push the Selic rate to a new low. With the economy set for a contraction this year and inflation falling to below 2.0% this week, we expect at least another 50 bps of easing. As of now, markets are pricing in a 75 bps cut, and given the recent strength in the currency, it is very possible the central bank cuts more aggressively than we expect.

Previous: 3.00% Consensus: 2.25%

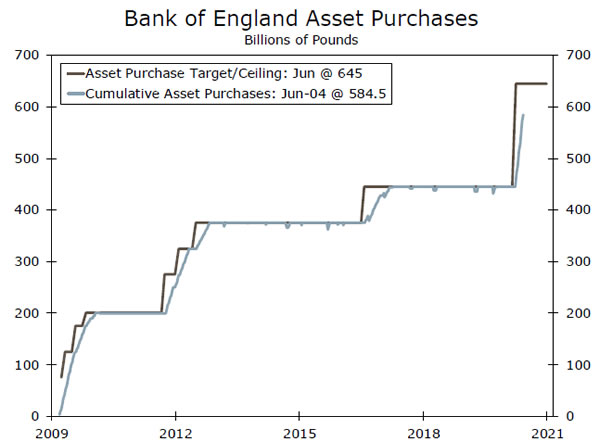

Bank of England • Thursday

The U.K. has been one of the most impacted countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. Not only from an economic perspective, but also from a health and human services perspective as it has seen close to 300,000 cases and a curve which has just recently begun to flatten. As the economic toll of COVID-19 builds, the Bank of England has moved quickly to ease monetary policy in an effort to offset the impact of the virus. Just this year, it has cut interest rates 65 bps to 0.10% and has embarked on a new asset purchase program. As of now, the central bank is targeting purchasing assets of £645B; however, we believe it will increase this target at the monetary policy meeting next week. In our view, it will get more aggressive and increase the asset purchase target £200B to £845B. In addition, we believe the risks around this forecast are to the upside, meaning the BoE could decide to target even more purchases.

Previous: £645B asset purchase target Wells Fargo: £845B asset purchase target

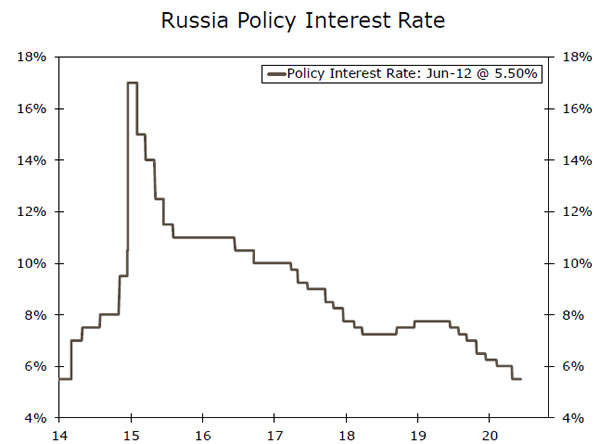

Central Bank of Russia • Friday

Monetary policy around the world has turned more dovish, with major central banks in the developed world cutting policy rates aggressively to counter the impact of COVID-19. The trend of easier monetary policy has been followed by central banks in emerging markets as well, as growth and inflation expectations continue to trend lower. In Russia’s case, the Central Bank of Russia has been cutting interest rates for some time now, and we expect it to be a bit more proactive at its meeting next week. In the midst of an economic slowdown led by COVID-19 and sharply lower oil prices, CPI has trended notably lower in Russia, well below the CBR’s 4% target. Comments from policymakers suggest the central bank could cut its key policy rate as much as 100 bps next week, while consensus forecasts currently expect 75 bps of easing. Either way, the message has been clear in that it will take all necessary measures to boost inflation and provide support to the economy.

Previous: 5.50% Consensus: 4.75%

Point of View

Interest Rate Watch

FOMC: Whatever It Takes

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) held a regularly scheduled meeting on Wednesday and, as largely expected, did not make any major policy changes. That said, the committee left little doubt that it will do “whatever it takes” (our words, not the FOMC’s) to help ensure that the economy crawls out of its pandemicinduced crater.

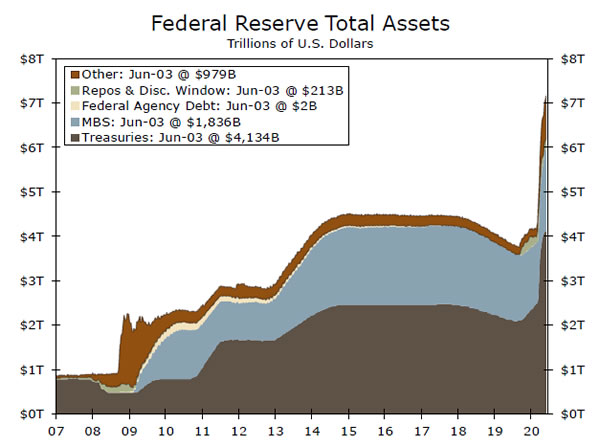

To underscore this point, the FOMC’s statement began by noting that it “is committed to using its full range of tools to support the U.S. economy in this challenging time, thereby promoting its maximum employment and price stability goals.” In that regard, the committee employed a form of implicit “forward guidance” in its so-called “dot plot. Specifically, 15 of the 17 committee members thought that it would be appropriate to keep rates on hold through 2022 (top chart). In other words, shortterm interest rates likely will remain at rock bottom for quite some time.

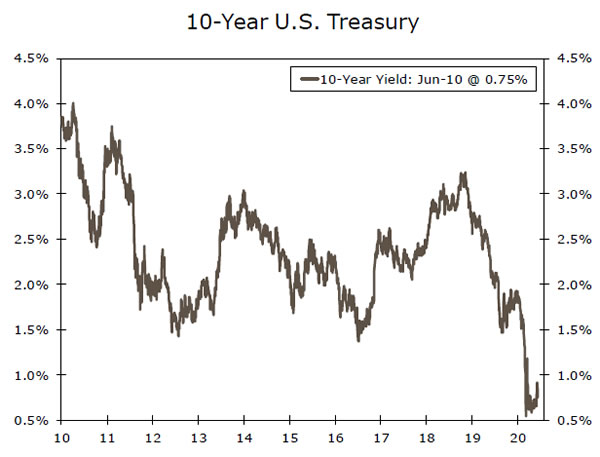

The FOMC also said that it will continue to purchase Treasury and mortgage-backed securities “at least at the current pace.” These purchases of securities have caused the Fed’s balance sheet to mushroom since the pandemic broke out (middle chart), and they also have helped to depress yields on long-term Treasury securities (bottom chart). Although the FOMC statement did not explicitly mention yield curve control (YCC), by which the Fed would target a long-term interest rate, Chairman Powell noted in his press conference that the committee did receive a briefing on the subject. So, YCC is under active consideration at the Fed. But as we wrote in a recent report, we do not think the committee is quite ready to move to explicit YCC.

That said, the tone of the policy statement, as noted by the opening sentence, left little doubt that the committee is prepared to use all of its tools to support the economy. If the deficit-induced flood of Treasury issuance puts upward pressure on the long end of the yield curve later this year, we have little doubt that the Fed will take steps, either explicitly or implicitly, to prevent a significant move higher.

Credit Market Insights

Turkey Agrees on Euroclear Deal

After multiple years of negotiations, the Turkish Ministry of Finance agreed with Euroclear—a Belgium-based securities clearing house—to allow international investors easier access to its local-currency bond market, at a time when the share of foreign holdings of Turkish bonds has fallen. According to a statement by Euroclear, the deal will allow foreign investors to have greater access to the Turkish government bond market, including Turkish lira, euro, U.S. dollar and gold denominated bonds, in a more secure and standardized way. Meanwhile, local issuers will have access to wider liquidity pools, and can potentially see less volatile borrowing costs. The move by Turkey is similar to Russia’s partnership with Euroclear almost a decade ago. However, given Turkey’s liquidity issues, which make it difficult for speculators to bet against the lira, and concerns that Turkish authorities may put restrictions on the currency, similar to capital controls, Turkey is unlikely to reap the same benefits that helped Russia’s financial markets.

Amid the recent risk rally, the lira strengthened to around TRY6.70. However, we continue to look for the currency to fall over the longer term as domestic imbalances within the economy persist, and political risks remain elevated. Although the Euroclear deal may boost access to Turkey’s local currency denominated bonds, we do not expect the deal to have a material impact on the lira.

Topic of the Week

Its Official, Recession Is Here

The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) determines the peaks (beginning of a recession) and troughs (end of a recession) of U.S. business cycles. Earlier this week, the NBER declared that economic activity in the U.S. economy peaked in February. In other words, the U.S. economy is currently in a recession. The previous expansion lasted for 128 months, which makes it the longest expansion in the history of U.S. business cycles going back to 1854. The NBER’s recession announcement was not a surprise for many analysts, due to the widespread COVID-19 related shutdowns. Although, we expect a short recession with positive GDP growth in Q3, it would be the deepest recession in the modern history, with a 12.3% peak-to-trough decline in the real GDP (top chart). The depth of this hole means it will take years to climb out. Specifically, our forecast for the level of real GDP at the end of 2021 would still be below the pre-recession peak by 2.5%.

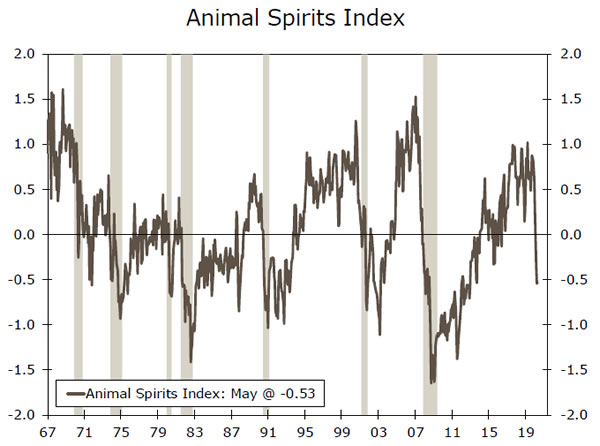

How quickly the economy is able to return to its pre- COVID-19 level of output will depend primarily on the virus, but also on consumers and businesses’ willingness to spend and invest. Our Animal Spirits Index (ASI) attempts to capture how people feel about the economy. Historically, our ASI has been a good indicator of the pace of a recovery. The ASI hit its lowest value on record (-1.65) in October 2008 and remained in negative territory until January 2014 (bottom chart). This was consistent with the recovery from the Great Recession, which is widely considered the weakest in the post-World War II era. In May, the ASI came in at -0.53, a slight improvement from April, but still firmly negative. Sentiment seems to be moving in the right direction, but it could take some time for the ASI to reach positive territory. We suspect that again sentiment will dictate the pace of recovery.