The trading session on Monday set to be at reduced volumes as the US and UK exchanges are closed for Memorial Day. Against this background, the dynamics of the currency market may be more revealing, and there is a reason for reflection. Today Beijing has lowered the official yuan rate to its lowest since February 2008.

The offshore exchange rate, USDCNH, reflects the height of disputes between the two major economies. At the same time, the official rate can be considered a very reliable indicator of the mood of Chinese politicians. Interventions to protect the renminbi rate were carried out by the PBoC with much higher efficiency and scope before essential agreements with the US.

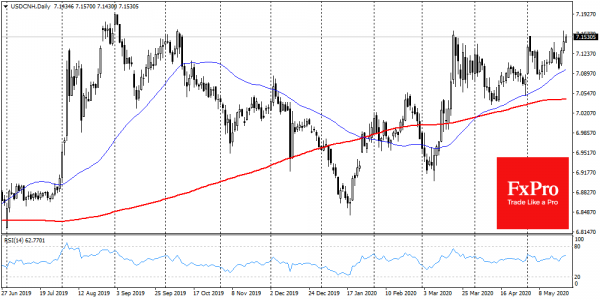

Offshore yuan rose to 7.15 – this is the area of peaks, where USDCNH grew amid aggravation of relations between China and the United States last year. That is, market pressure on the exchange rate was not as intense as before, although the PboC weakened its support for the yuan.

This is a clear clue from Chinese bureaucrats that they intend to use the cheaper renminbi rate as a measure to support China’s export competitiveness. The lower exchange rate has always been a reason for anger from the US, and it promises to be the same this time.

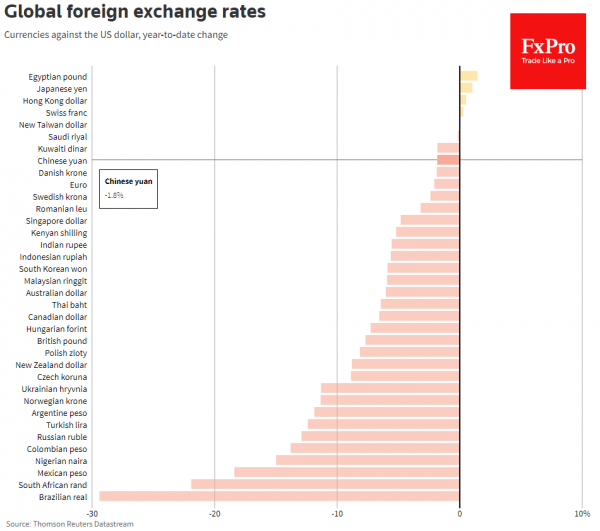

For many other currencies in developing countries, the Chinese yuan is much more resistant to the dollar, losing just 1.8% so far this year. But for a long time, it has been directly pegged. Therefore, a renminbi depreciation against the dollar promises to attract increased attention from politicians.

However, the dollar is also strengthening against most other currencies. And this is an essential message to the markets that massive purchases by the Fed through the “dollars printing” are not a signal to sell it. Just the opposite, while the US Treasury is pulling money out of the global financial system to finance its needs – the dollar may be one of the most stable currencies.

Historically, the dollar weakens when the world economy enters a synchronous acceleration. Under these conditions, capital is heading to a more yielding direction than US government bonds. Also, there may be a large amount of it not only in nominal terms but also relative to the country’s GDP.

The weakening of the dollar, along with rising inflation is the most common and mild way for large countries to reduce their debt burden. It is a much gentler way than devaluation to the price of gold (1933) or complete abandonment of this peg (1971). And certainly more suitable for creditors and the financial system as a whole than the default on government bonds that Argentina allowed last week.