The past week continued to highlight some green shoots in economic data for May – not itself surprising given the increasing number of regions/countries beginning to ease COVID-19 containment measures. The early round of PMI measures for May generally were less-bad than in April, although still flagging a historically soft level of activity persisting, particularly in the services sector. Canada is not one of the countries to get an advance PMI reading, but survey numbers from the Canadian Federation of Independent Business have also ticked higher into early May, and our own tracking of credit and debit card spending trends continues to look a bit better. That does not mean it will be a quick bounce-back. Consumer confidence edged only marginally higher in May from historic lows in April. And cumulative unique applications for the Canada Emergency Response Benefit have continued to rise, albeit at a sharply reduced rate compared to March and April.

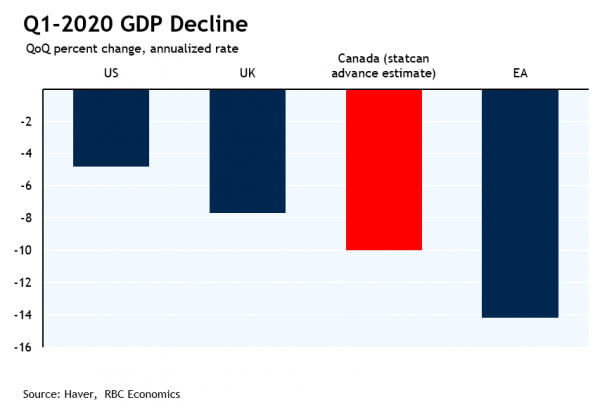

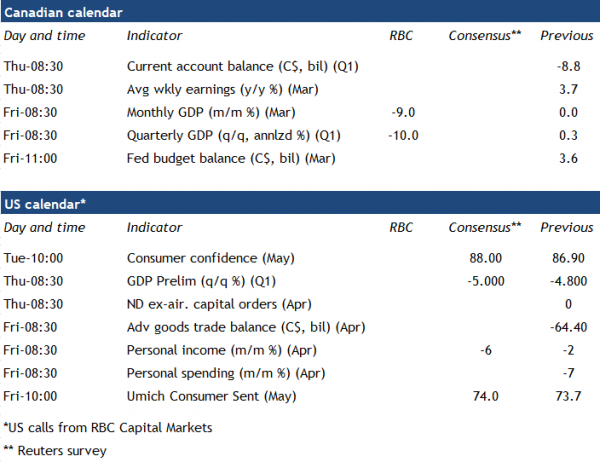

Backward looking economic data in Canada has also not been quite as bad as perhaps feared. Reports on manufacturing and retail sales for March (and in the case of retail, with an advance estimate for April spending) were both exceptionally soft, but with details that were a little less-bad than we were assuming. Housing starts held up almost shockingly well in March and April. Still, in this unusual downturn, other service-sector industries that are normally more resilient likely led the slowdown. Industries like accommodation, arts & entertainment, education, even healthcare for which early indicators are limited were certainly exceptionally soft over the back half of March. Statistics Canada already reported an advance estimate that GDP declined 9% in that month as a whole and 10% (at an annualized rate) in Q1. Industry reports since have been, on balance, still consistent with that. Apart from Canada, other countries have reported sharply lower activity in Q1 as well. US Q1 GDP fell by 4.8% annualized, showing massive pullbacks in consumer spending (mostly in services consumption) as well as business investment. UK GDP fell 5.8% in the month of March and almost 8% annualized in Q1.

A less-closely-watched, but still important, economic release in Canada will be the SEPH job count for March to be released a day ahead of the March/Q1 GDP data. We already know that employment fell precipitously by mid-March given the unprecedented (at least until the April numbers were released) 1 million decline in employment reported for that month in the earlier-released LFS data. But the SEPH survey reference period was a week later than the LFS numbers, and so will have captured more of the job losses towards the end of the month. The SEPH employment numbers are also generally viewed as a more reliable indicator of wage income. If the earlier-released employment numbers are any guide, job losses in March were heavily concentrated at the lower end of the wage scale, and probably among hourly rather than salaried employees. Employment losses among lower-wage households is of course itself bad news, but novel government income support programs are also relatively more generous at the lower end of the wage distribution. The earlier LFS labour market data showed 40% of job losses over March and April were in jobs that usually pay $500/week or less, meaning many could see income losses significantly offset by the $2000 per 4-week payments under the new, but temporary, CERB program.