The euro finally found its footing this week, bolstered by a Franco-German plan for a European recovery fund worth half a trillion euros to assist the economies most devastated by the crisis. Although the proposal is a step in the right direction for establishing some debt-sharing mechanism that ultimately sets the stage for Eurobonds, its size is quite small and it will face fierce opposition from Northern European countries. Hence, while it diminishes some risks and could keep the euro afloat for now, it’s probably not a game changer.

A surprisingly daring plan

Few expected a proper recovery fund to be established in Europe, and even fewer expected it to come jointly from France and Germany, as the latter is often criticized as an opponent of European fiscal integration. But it did, and the most surprising part was that both nations were adamant the funds should be given as grants from the EU budget, not loans that would have to be paid back, so nations like Italy with high debt levels can get some real relief.

While many details and ‘criteria’ are still unknown, it seems the funds will be allocated to the worst-hit countries and sectors, and the program could be approved at the June 18 EU meeting, provided the whole of the EU is on board.

The good news: Hello fiscal integration

This is a welcome show of solidarity, especially when sponsored by the two biggest European economies. And by targeting the most affected regions it could lay the foundations for a more ‘well rounded’ recovery. It might also calm anti-EU sentiment, especially in Southern Europe, lessening the risk of a Eurozone break-up.

The bigger point though, is that if this succeeds, it sets a precedent in terms of risk sharing. The euro area’s Achilles’ heel is the lack of a fiscal union, meaning that there is no real federal government like in the US that can help individual states when they are in trouble. Although this proposal wouldn’t truly fix that institutional weakness, it would still be a baby step in the right direction.

The bad news: It’s small, and will be watered down

Unfortunately, its sheer size is not enough, as 500bn euros amounts only to 3% of EU GDP. One can argue the EU Commission has also announced other programs, but even adding everything together, the total size isn’t impressive.

Moreover, this is far from a done deal. Austria, the Netherlands, Denmark, and Sweden, have all voiced disagreement to the Franco-German proposal, with Austria’s Chancellor categorically refusing to support any grants. He wants the assistance to be given in loans instead. The issue is that all these nations are net contributors to the EU budget, so they don’t want to ‘pay’ for stimulus that will mainly benefit other economies.

While any of these countries can theoretically veto the proposal, in reality, they will have a hard time standing in front of the Franco-German bulldozer. If the UK was still part of the EU, it would be a different story. But with the UK out, France and Germany hold most of the political capital, and when they agree on something alongside Italy and Spain, it’s likely to get done eventually.

That said, while these smaller economies may not block the package entirely, they can probably exert enough pressure in negotiations to water it down, for example by reducing the amount of grants and substituting them with loans. Hence, not only is the package small, it might also look much different – and less powerful – in its final form. Not to mention that the negotiations could take a long time to wrap up.

Euro: Encouraging development, but not enough

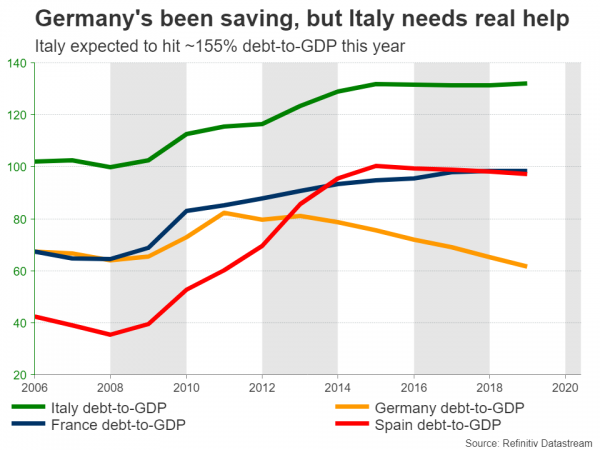

As for the single currency, while this is clearly a positive development, it doesn’t really change the broader negative outlook. The EU suffers from a weak institutional infrastructure, and until the problem of debt sharing has been properly addressed – for example by introducing proper Eurobonds – the risk of new debt crises will continue to haunt markets like Italy, even if this proposal will help with that a little.

Ultimately, this makes Europe a region of slow growth, which could matter a lot coming out of the crisis, especially in a post-corona world where even export powerhouses like Germany might struggle to find buyers for their products.

In the shorter term, there’s still the issue of getting through the negotiations for this package, and also of whether the ECB will ramp up its bond-buying program at its upcoming June meeting.

Does the dollar side of the equation matter more?

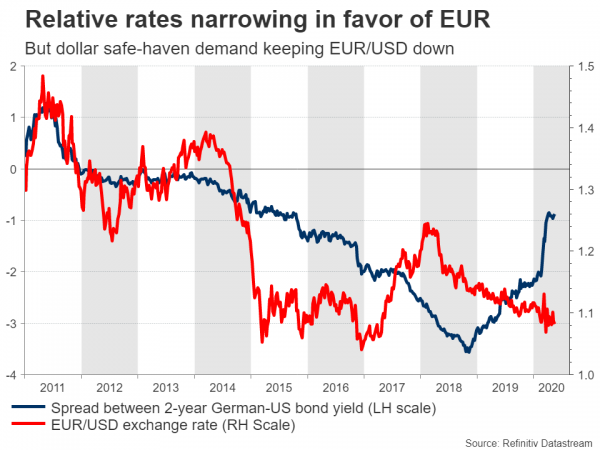

All told, it’s probably much too early for a healthy and sustainable rally in the euro, even if this announcement diminishes the worst downside risks. In fact, the euro’s best chance of gaining from here may have more to do with the dollar, rather than itself. The greenback has remained stubbornly strong throughout this crisis despite the Fed’s best efforts to weaken it, as investors flock to the safety of the reserve asset.

Until the global economy gets its feet under it, the dollar is unlikely to lose its haven shine, so any powerful upside in euro/dollar seems unlikely. But once this crisis blows over, then the stage will be set for a move higher in euro/dollar from current depressed levels – not because the euro will suddenly be more attractive but rather because the dollar will no longer be ‘the only game in town’.