The virus pandemic continues to wreak havoc on the global economy and financial markets. Stocks are in freefall, commodity currencies are getting hammered, and even safe havens like gold can’t shine as the market meltdown is forcing major funds to deleverage by ‘selling everything’. In this panicky environment, investors are unlikely to pay much attention to economic data, though the US initial jobless claims might be an exception. The big winner from all the chaos is the greenback, which has exploded higher amid a dollar liquidity shortage of epic proportions.

‘Panicdemic’ hits Europe

Global markets are on fire. The virus outbreak has sparked fears of a deep recession, as consumption is set to collapse with people staying at home, leading to a cascade of rising unemployment if companies hit the panic button too and start cutting costs. Central banks and governments have thrown the kitchen sinks at the problem – cutting rates to zero, relaunching QE programs, and announcing huge spending plans to support smaller businesses and employees – but none of it has been enough to calm the nerves of investors.

In these circumstances, economic data might not mean much. Markets are panicking about the effects the quarantines will have on consumption, but considering how recent these lockdowns are, the data for March are unlikely to capture their full impact. In other words, economic data for March might be seen as outdated. That said, downside risks still exist. Whereas investors might ignore surprisingly strong figures as being outdated, they could still panic on disappointing numbers, fearful that the situation will get much worse in April.

Europe is at the epicentre of all this, with most economies now in lockdown. Therefore, the Eurozone’s preliminary PMIs for March that are due on Tuesday could attract some attention, but as per above, even those may not shake markets all that much – and the risk is to the downside.

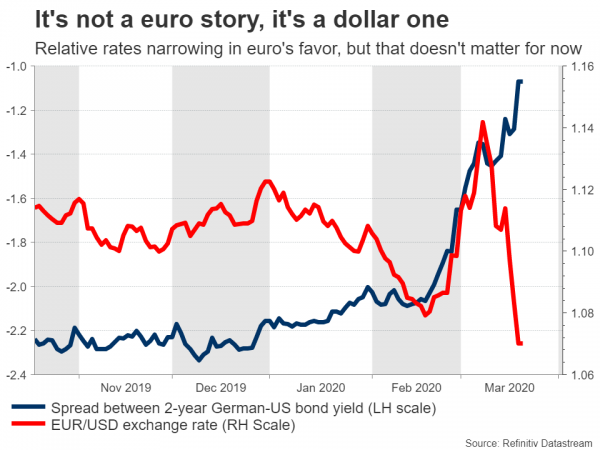

Euro/dollar plummeted aggressively lately as the carry unwinding that was boosting the euro came to an end at a time when a dollar shortage emerged. Distressed companies and funds around the world are rushing to find dollars to secure their future cash flow needs, hedge currency positions, and cover margin calls, all amid a general flight to safety.

The bottom line is that until the market panic subsides, it’s difficult to envision a sustainable turnaround in euro/dollar. That said, the euro has been remarkably stable against the defensive yen and has even gained against the pound, so this is mostly a dollar story.

Emperor dollar takes no prisoners – intervention possible?

Admittedly, the speed of the dollar’s latest rally is breath-taking. Investors and companies are rushing into the world’s reserve currency, for different reasons. Businesses are uncertain about their future revenues amid the pandemic and the lockdowns, so they are scrambling to secure dollars to meet their upcoming payments. On the financial side, funds – especially leveraged ones – that have experienced heavy losses in stocks lately need dollars to cover margin calls or hedge bets.

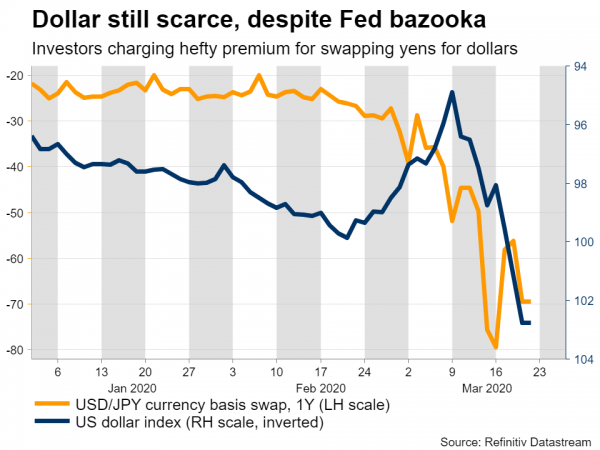

For now, there’s little to suggest that this dollar shortage has run its course. Currency basis swap spreads – which show the cost of borrowing dollars abroad – remain wide, signalling that banks still charge investors a hefty premium for swapping yens for example, for dollars. Hence, markets remain stressed and the dollar is still in short supply, despite the Fed opening hundreds of billions in swap lines to foreign central banks to ease this dollar shortage.

But a strong dollar is not a blessing. The more the dollar rises, the more financial conditions ‘tighten’, not just in the US but globally too. A stronger greenback makes US exports less competitive, puts extreme strain on emerging market economies with debt denominated in dollars, and could force foreign central banks to raise rates to defend their currencies from depreciating further, as Denmark did yesterday.

Therefore, market chatter increasingly suggests that the Fed – in coordination with other major central banks – might intervene in the FX market to weaken the dollar. Admittedly though, the situation doesn’t look dire enough to warrant such drastic measures, at least for now. Having said that, the more the dollar strengthens from here, the higher the likelihood that such an intervention materializes.

In terms of the data, the most important release will be the weekly US initial jobless claims on Thursday. This will be the first piece of data to really capture the effects of the virus, with investors eager to see whether the lockdowns in many states have already caused mass layoffs at restaurants, bars, or hotels. The risk is clearly a huge surge in the number of Americans filing for unemployment benefits, which could spell bad news for risk sentiment as it would further raise the probability of a recession.

The preliminary Markit PMIs for March – due on Tuesday – could also capture market interest. Durable goods orders for February will follow on Wednesday, ahead of personal income and spending data alongside the core PCE price index for the same month, all on Friday.

Cable drops to multi-decade lows

In contrast to the dollar, the pound has been one of the weakest members of the G10 FX club lately, amid brewing concerns around the government’s delayed response to the virus outbreak, which has seen it fall behind the rest of Europe in terms of quarantine measures. The emergency rate cuts by the Bank of England (BoE) and a colossal fiscal stimulus that could jeopardise the UK’s long-term fiscal health didn’t help either. The government announced GBP 330bn – equal to 15% of GDP – just for business loan guarantees, on top of many other spending measures.

Beyond cutting rates to 0.1%, the BoE also scaled up its QE programme yesterday in an unscheduled, emergency meeting. This takes the focus away from the central bank’s regularly scheduled meeting, which was planned for Thursday, as any more stimulus seems unlikely for the time being. Even if the Bank wanted to, it has now almost exhausted its conventional policy ammunition.

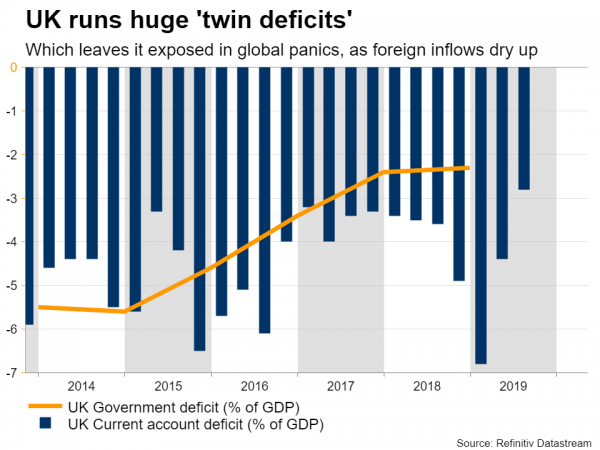

As for the pound, the recent weakness seems a little overdone. Granted, the UK runs a large current account deficit, and now, it will also run a huge fiscal deficit. This implies the British economy is highly exposed in times of global turmoil, when investors go on the defensive and no longer invest in Britain. Outgoing BoE Governor Mark Carney once described it as “relying on the kindness of strangers”.

However, the extraordinary stimulus measures could pay dividends down the road. Relative to its size, the UK has announced the biggest fiscal package to date, which will likely keep the economy from going off the rails amidst this crisis. In this light, a virus shutdown of the economy – like most of Europe – might even be the trigger for a rebound in the pound. It would imply less contagion, and alongside the enormous stimulus, that could paint a brighter long-term picture for the economy.

On the data front, all eyes will be on the preliminary PMIs for March that are due on Tuesday for an early assessment of the virus impact. CPI inflation and retail sales numbers for February will follow on Wednesday and Thursday respectively.