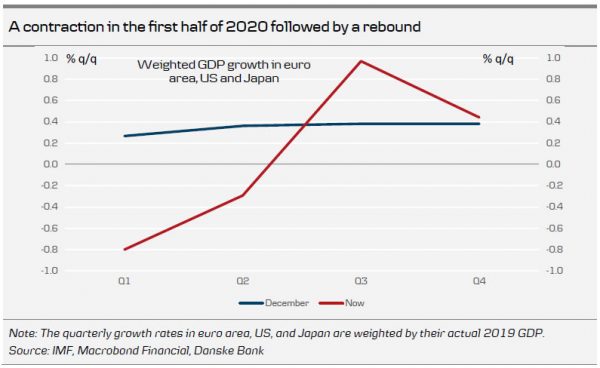

- With the spread of the COVID-19 virus and the forceful restrictions being put in place together with elevated financial stress, we expect the global economy to fall into a recession in Q1 and Q2 and probably the early part of Q3 too followed by a recovery over H2.

- The sizeable economic slowdown will lead to a higher unemployment rate in western economies, especially for temporary workers in the service sector, but the rise should be cushioned by government labour support schemes in Europe and the US.

- However, there are rays of light in China (and to some extent South Korea) where the virus has been got under control and production has returned to normal in many places, benefiting the global value chains.

- The efforts to contain the virus should at some stage during the spring limit the virus in western countries, which, together with a significant policy response and sizeable household buffers, should avoid the crisis turning into a prolonged recession.

- However, it must be said that the situation and hence our forecast remain highly fluid at this stage.

A technical recession is now our base-case

In our piece The Coronavirus Crisis U-shaped rather than L-shaped global recovery, we argued that the coronavirus crisis would deal a blow to the global economy, but given the assumption of a fairly contained spread of the virus, the restrictions to limit the spread of the virus would be relatively benign and concentrated mainly to Italy and Asian countries. Then as the virus receded, we saw a u-shaped recovery taking place in late Q2. At the same time, we saw a considerable risk that the downturn could become deeper and more entrenched if the virus were to spread more aggressively, leading to more widespread lockdown of economic activity in Europe beyond Italy and a surge in financial stress.

These downside risk factors are indeed now materialising. The virus outbreak is now regarded as a global pandemic. In Europe and the US, the surge in the number of infections is leading to more forceful policy measures to restrict the spread of the virus, such as the national lockdown in Italy and similar actions in Denmark and other European countries. These actions have serious economic repercussions in terms of lower private consumption and hits to supply chains. At the same time, the surge in financial stress, including wider credit spreads, and sharp falls in global equity markets will lead to lower investment and some wealth effects on private consumption.

In light of these developments, we see the global economy falling into a technical recession in the Q1 and Q2 and probably early part of Q3. The economic impact will somewhat differ timing wise across European countries. Italy will likely be the first to see the number of infections go down, for others the hit will extend into Q2. We see negative quarterly growth in the Eurozone, US and Japanese economies in these quarters.

In China the virus has been got under control and production has returned to normal in many places. However, China will be hit by the sharp slowdowns in US and Europe in Q2 and we think the expected Chinese recovery will be more drawn out. Investment spending will stay subdued due to the high level of uncertainty and exports will suffer. Service sector activity will also move up only gradually. In the second half, we still look for higher growth in China on the back of higher growth in the rest of the world and stronger domestic spending as a rebound from the curtailment in spending caused by COVID-19. We have lowered our GDP forecast for 2020 further from 5.4% to 5.2%. However, we now look for GDP growth in 2021 at 6.3% as there will be a bigger catch-up effect.

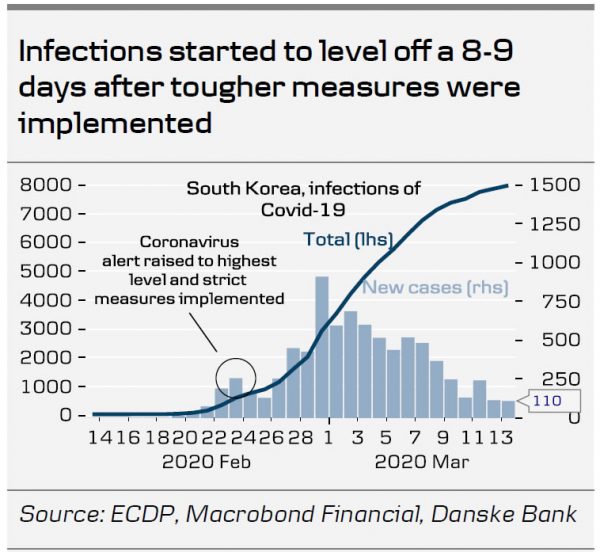

South East Asia has seen encouraging signs regarding the spread of the virus. Particularly in South Korea, which has been the country with the third most infections only surpassed by China and Italy, the contamination seems to be getting under control. Despite the struggle to get there, exports for early March held up quite well, which is encouraging given the importance of South Korea in the global value chain.

Japan has also imposed harsh restrictions, which are inevitably going to hit domestic demand hard. In Japan, it is paramount that the spread of the virus is contained and does not drag out. If it does drag out, there is a risk that the Tokyo Olympics will have to be cancelled, which would be a huge blow to the economy. That means politicians are likely to prefer the economy takes a big hit now to heighten the chance of containing the spread earlier, which is indeed what is reflected in its restrictions, with the closing of schools when the infection rate was still only at 1.6 per million people.

However, the sizeable but in our view temporary economic slowdown will lead to rising unemployment rates. This will especially be the case for temporary workers in the service sector, which will be hit the hardest by the coronavirus-restrictions and fear. However, in our base case of a temporary recession, the rise will not be as pronounced as in a scenario of a more prolonged recession. First, especially in Europe, it is more expensive to hire and fire employees. Second, we think that European countries will follow the Germany “kurzarbeit” approach, whereby workers are retained at reduced hours and cost, with the support from the government.

We think the global economy will see a recovery starting in earnest in Q3. Part of this will be some ‘catch-up’ in production as inventories are worn down (this effect could happen earlier) and as the corona related restrictions are set to slowly ease in societies over the next couple of months (see our discussion on our assumptions on the virus below). Some postponed business spending will also come through, boosted by the cheap money given the easing of monetary policy and lower oil prices which will boost real income growth over the next months. Demand will also increase (albeit slower than production) as it will take time for consumers to regain their confidence and for restrictions to be eased on travelling and social gathering. The real GDP growth rate for the 2020 for US, euro area, and Japan, are 1.0%, 0.1% and -1.5%, respectively, rebounding solidly to 1.9%, 1.2% and 1.2% in 2021.

Why do we not expect this to involve into a prolonged recession?

Containing the outbreak will be key to the outlook for the global economy over the coming quarters. In the short term, we expect the virus numbers to get worse in Europe and the US. The two regions are still in phase one of the transmission of the virus, in which it grows exponentially by around 25-35% per day. However, within the next two-three weeks we expect Europe to enter phase two, in which the number of new cases slows down in response to both the restrictions imposed by governments and the fact that fear is spreading over the virus and people increasingly stay inside, avoiding crowds and limiting travel by public transport or airplanes. Since the US is the latest place COVID-19 spread to, the numbers there are likely to respond with a lag of 1-2 weeks of what we see in Europe. As we get into April, we look for Europe and the US to enter phase 3, in which the contagion comes down a lot and, going into May, we should also get help from warmer weather. Judging from the geographical spread of the virus, temperature seems to matter for the COVID-19 virus, as we are not seeing the exponential development in regions with warmer weather. The cases we see there are mostly imported cases.

We think policy makers will do “whatever it takes” to help prevent the crisis turning into a permanent shock, where rising unemployment and bankruptcies ignite a vicious cycle. On the fiscal side, both EU countries and the US, following China and Japan, are rolling out fiscal aid packages aimed at mitigating the possible hit to companies from the slump in revenues through deferred tax payments and support schemes to avoid largescale lay-offs (along the lines of the German Kurzarbeit scheme). As long as the shock is temporary, hitting only certain sectors of the economy, this approach seems to us appropriate. More broad-based fiscal easing, such as infrastructure programmes, may come too late, while tax cuts may be saved as people will be reluctant to go out and spend the extra income. In that sense, a broad based fiscal expansion would help the economy recover, but only once the concerns about the virus ebb.

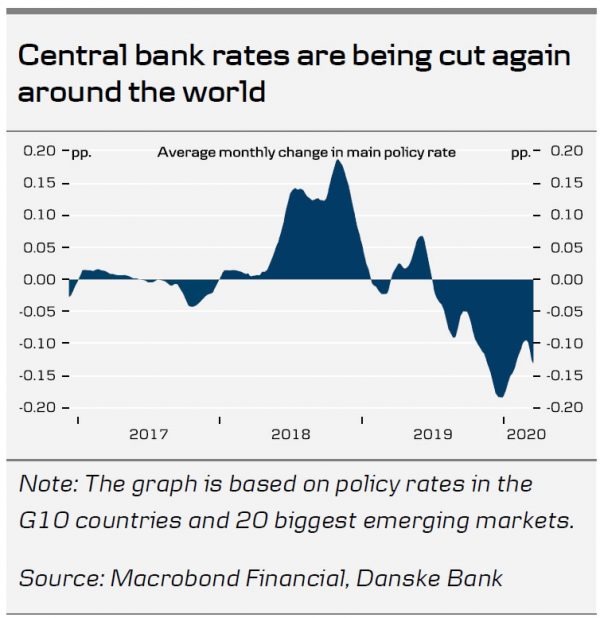

On the monetary policy side, central banks with policy space are cutting policy rates and others are providing targeted liquidity to aid banks and the economy. The Fed, BoE, BoC, BoA, Norges Bank and PBoC have all cut rates. Last night the Fed cut its policy rate by 100bp and signalled they will restart QE as well. In addition, it has supplied a lot of USD liquidity to the market. Other central banks with more limited policy space, like the BoJ and the ECB, have instead of rate cuts initiated different liquidity enhancing operations to boost banks’ lending capabilities.

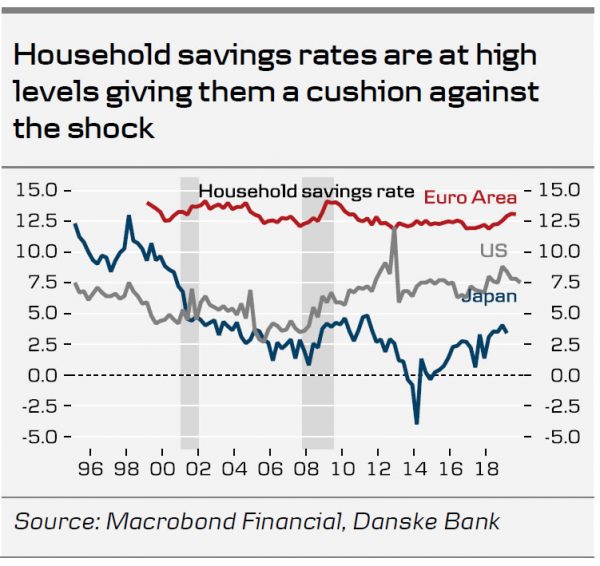

Furthermore, unlike the onset of a traditional recession, households have bigger buffers in terms of higher savings rates. Typically, savings rates are quite low at the start of recession, when optimism has ignited a spending boom. However, currently consumers have quite high savings rates, giving them the option of increasing spending both during the shock but especially after the crisis abates (their saving rate may temporarily increase over the next few months as they hold back on travelling, entertainment and large-scale shopping of durables for example, but then they can lower it again).

What could go wrong?

Obviously, uncertainty is extraordinarily high at the moment and we could be wrong on some of our underlying assumptions, which could take us into a nastier scenario with a protracted recession.

- The virus could prove harder to contain and continue to spread into the summer and the fall. We believe the experience from South Korea and China indicates that once the right measures are taken and people start to stay inside, the virus slows significantly. But if policymakers fail to take the harsh measures needed, the spread of the virus could continue for longer than we assume. The hope that warmer temperatures will help tame the contagion could also prove to be wrong, as there is no hard evidence of this yet (although there are some indications that the virus has not yet spread widely in the warmer regions of the planet).

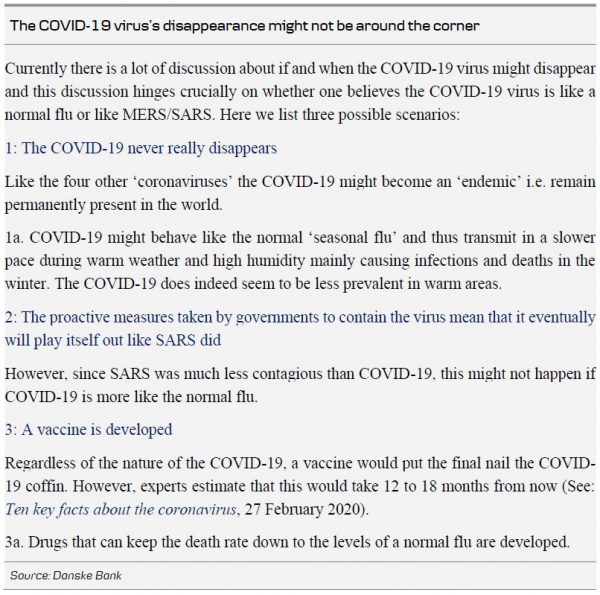

- There is also a risk that the virus could return in the autumn when the weather gets cooler again and life has returned to normal with people moving around again (see box on page 5). While it could return, several promising drugs seem to be under way that could help treat the disease and reduce mortality, see here article from The Guardian, 10 March and The German Primate Centre, 5 March. However, if there are no drugs by autumn and the virus starts spreading again, we would likely see a quick fall-back in growth again and be heading for a longer recession.

- Another risk is that the shock becomes so big that you reach a tipping point after which the health crisis turns into a financial crisis, with a negative spiral of bankruptcies, credit crunch, rising unemployment etc.

- We assume that policy makers will eventually do ‘whatever it takes’ to avoid the above scenario. However, this could prove wrong if policy makers misread the situation and act too late or simply cannot agree in Washington due to a political bi-partisan stand-off.

- Supply chains are likely to be affected by the significant restrictions put in place. As we have not in recent history experienced a scenario like this before, it could turn out that these disruptions become so big that the negative impact on the global economy becomes so big that it pushes us into a longer lasting recession.