Executive Summary

- U.K. monetary and fiscal authorities announced a raft of support measures for its economy today as it grapples with the early stages of its own coronavirus outbreak. While some of the tools being used are perhaps blunt in nature, many of the measures are more targeted at supporting sectors of the economy that are likely to be hit hardest by the virus outbreak.

- The Bank of England (BoE) has now cut rates effectively to zero, and we are not at this stage expecting any further cuts that would take rates into negative territory. If the BoE feels the need to take further action on the monetary side, asset purchases seem to be a likely candidate. Meanwhile, in addition to temporary virus-related measures, the government’s budget calls for a material change in the trajectory of public finances that should be an upside risk for U.K. growth, interest rates and the pound over the longer term.

Monetary and Fiscal Policy, Together at Last

The Bank of England (BoE) and U.K. Treasury announced a coordinated package of stimulus measures for the U.K. economy today. First, the BoE announced a 50 bp cut in the Bank Rate to 0.25%, and while we had previously forecasted that the central bank would cut rates by 50 bps, we admittedly had not expected it to do so as quickly as it did. At this point, we are not expecting any further BoE rate cuts. Overnight interbank rates have tended to trade just below the BoE’s target for the Bank Rate, and so if the BoE cuts rates to zero, some interbank rates would likely turn negative, something the central bank may wish to avoid.

In addition to the rate cut, the BoE announced a new Term Funding Scheme with incentives for small and medium sized enterprises (TFSME). This is a program that offers low cost, long-term funding to banks and incentivizes those banks to lend to the real economy, particularly small and medium-sized businesses. Specifically, it offers banks four-year loans at or close to the Bank Rate (0.25% at present), with the exact cost and borrowing limits dependent on the extent to which banks provide loans to the real economy—the more that banks lend, the more they can borrow and the lower their borrowing rate will be through the TSFME. This program is akin to the European Central Bank’s Targeted Long-Term Refinancing Operations (TLTROs), and should support U.K. banks and the businesses they lend to as they navigate the next few months of economic challenges. U.K. bank supervisors also announced they would reduce the countercyclical capital buffer (CCB) rate to 0% from 1% for the nation’s banks. This step effectively relaxes the requirements on banks to hold capital against their assets, making it easier for those banks to expand credit and to manage their balance sheets more broadly.

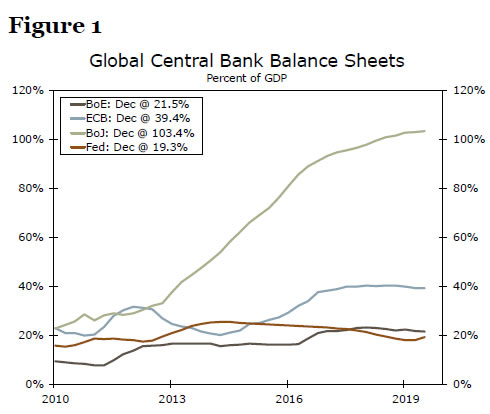

These measures, in our view, will be crucial in supporting the U.K. banking system, as well as the broader economy, over the next few weeks and months as the economic effects of the virus outbreak continue to reverberate. One legitimate concern, however, is that the BoE has very limited further policy space now that it has cut rates effectively to zero and launched its TFSME. The next logical step would in our view be additional asset purchases. The BoE has not announced new net asset purchases since late 2016, when it resumed purchases amid recession fears following the June 2016 Brexit referendum. Since then, however, it has merely been rolling over its existing asset holdings rather than increasing its stock of assets. As the chart below shows, the BoE’s balance sheet is just over 20% of GDP, more or less in line with the Fed and well below that of the ECB or BoJ. This suggests there is some additional scope for new net purchases of both Gilts and corporate bonds should the BoE deem such action warranted. However, there are legitimate questions of whether additional asset purchases alone would be a sufficient policy response, given the extent of economic disruption at this point is unknown.

U.K. Chancellor Breaks Out the Big Guns

Fortunately, the U.K. government also announced a series of coordinated policy measures today that should also help offset the economic impact of the virus outbreak, in addition to its announcement of its broader budget plans over the next several years. Some of the virus-related measures that were announced include:

- Roughly £1B in welfare spending, including more generous statutory paid sick leave. For private small businesses, the government will cover the cost of paying sick leave for absent employees for up to 14 days.

- A new temporary lending scheme for small businesses affected by the virus, offering loans up to £1.2M through U.K. banks, with the government covering up to 80% of losses on those loans if necessary.

- Business rates, or taxes on businesses operating in commercial property space, are abolished for 12 months for small businesses in the leisure and hospitality sector.

- Cash grants worth up to £3,000 for 700,000 of the U.K. smallest businesses.

In total, these extraordinary virus support measures amount to roughly £7B in stimulus this year, which in addition to a £5B emergency response fund for NHS and £18B of support in a separate proposal amounts to a total of £30B pounds (1.3% of GDP) in net new stimulus this year. These measures are, in the words of U.K. Chancellor Rishi Sunak, targeted and timely, and in our view will help to offset some, although far from all, of the hit to the U.K. economy from the virus. The U.K. government downgraded its 2020 forecast for U.K. GDP to 1.1%, but we think this is still too optimistic, as we expect growth of just 0.7% this year.

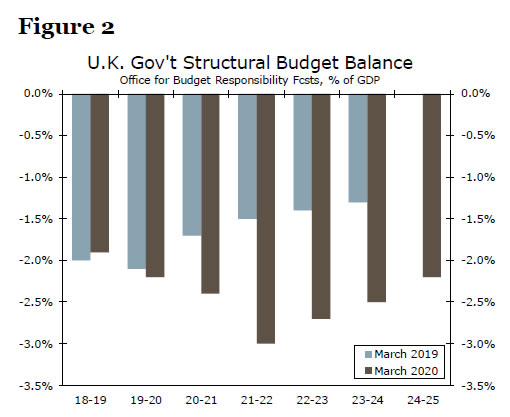

Looking further out and beyond the virus-related measures taken by the U.K. government, the newly announced 2020 budget represents a substantial longer-term increase in stimulus from the prior budget. Figure 2 shows structural budget balance projections from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), which show that based on the prior budget, the OBR projected fiscal policy would begin to tighten (i.e. the structural deficit would narrow) starting in the 2020-21 fiscal year. However, fiscal policy is now projected to become significantly looser through the 2021-22 fiscal year now, with the structural deficit peaking at nearly 3% of GDP, before gradually becoming more restrictive in the following years. Importantly, this implies a mere stabilization in the debtto- GDP ratio, whereas the prior budget had called for a reduction in the debt ratio over time.

The higher spending appears to be particularly targeted in infrastructure, with £600B allotted to various projects over the next five years (around 5% of GDP every year for five years). We would certainly take the under on this number, but the broader point that is in our view important to focus on is that the U.K. seems to have set aside concerns around budget sustainability for the time being. That fundamental shift in budgetary position is significant and in our view poses some upside risk over the long-term for U.K. GDP growth, bond yields and the British pound.