As stock markets reel from the coronavirus, and investors flee to safe havens such as the yen and gold, the US dollar has turned out to be an unexpected casualty of the market turmoil. But after emergency rate cuts failed to lift sentiment, some movement on the fiscal policy front has managed to soothe investor nerves, at least temporarily, giving a small reprieve to tumbling bond yields, and in turn the greenback.

Stocks suffer steepest losses since financial crisis

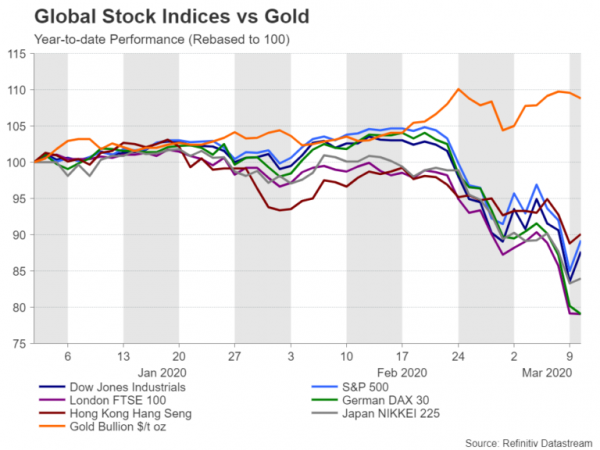

Fears that the outbreak of the coronavirus will only get worse and inflict heavy damage on the global economy sent stocks spiralling downwards on Monday, with major indices recording their worst one-day loss since the 2008 financial crisis. With no end in sight to the rapid spread of the virus, investors are predicting the worst, with many forecasting a global recession.

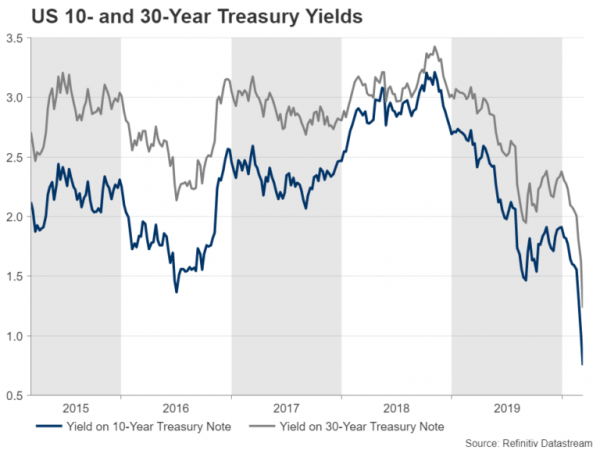

It’s no wonder therefore that traditional safe havens such as gold have been on the receiving end of this flight to safety. The precious metal broke above the $1700/ounce level this week for the first time since late 2012. But other traditional haven assets like government bonds have also seen demand surge. German 10-year bunds hit an all-time low of -0.909% but the most dramatic move came in US Treasury notes. The yield on long term Treasury notes plummeted to record lows, with the 10-year yield dropping below 0.5% at one point and the 30-year yield below 1%.

Dollar pummelled by collapse in yields

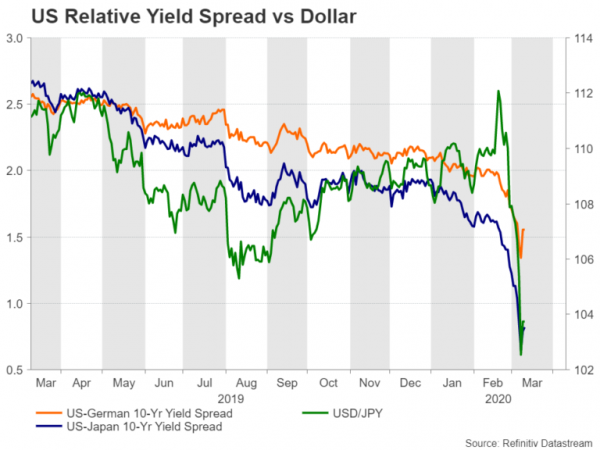

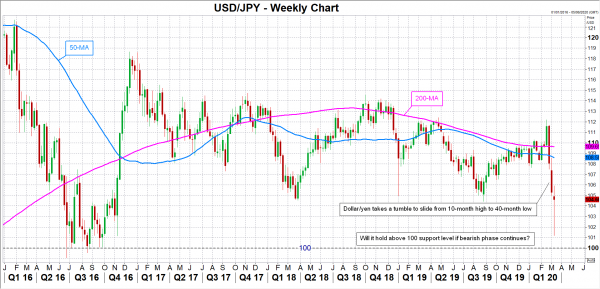

The collapse in yields has subsequently wiped out the dollar’s main advantage over its major peers and last week the currency had its worst weekly performance in four years. Dollar/yen has been particularly hammered, diving about 10% from the February peak of 112.21 to this week’s 3-year low of 101.17. The combination of falling US yields and rising safe-haven demand for the yen have been devastating for the pair.

But what fuelled this sudden plunge in yields? The Federal Reserve’s emergency rate cut of 50 basis points (bps) on March 2 was the primary trigger, though yields had started to turn lower in late January when investors first began worrying about the potential virus impact on China’s economy. However, the speed and scale of the ensuing decline in yields has taken everyone by surprise and the Fed’s intervention appears to have reinforced the market’s view that the US central bank won’t hesitate to act in supporting the economy through the crisis.

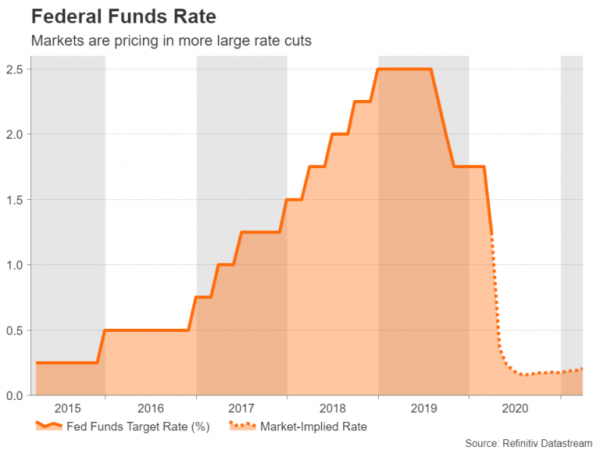

Fed funds rate could soon reach zero

Rate cut bets have been fluctuating wildly since the virus outbreak started escalating into something more serious. Fed funds futures currently imply a rate cut of almost 75 bps at the March 17-18 policy meeting but have shown to be highly sensitive to expectations for fiscal stimulus. With follow-up cuts likely to come at subsequent meetings, it now seems only a matter of time before rates in the US hit rock bottom like they did during the financial crisis.

The coronavirus epidemic does not look like it will be dissipating anytime soon as the number of cases outside of China continue to multiply at a worrying rate. And although Chinese authorities finally seem to be getting a handle on the situation, any future rebound in China would likely be short-lived if the rest of the world is under lockdown.

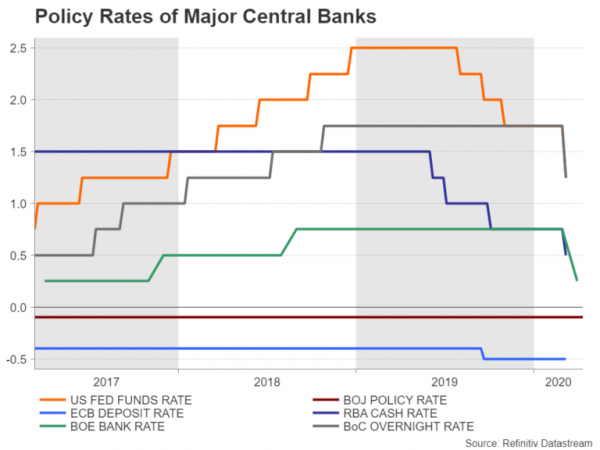

ECB and BoJ may fail to match expectations

One can only deduce therefore that the economic disruptions created by the outbreak won’t be subsiding quickly and it may be several more months before the virus is fully contained. In the meantime, the pressure is on governments and central banks to shore up their economies with stimulus measures.

The Australian, Canadian, UK and US central banks have already slashed borrowing costs. Investors’ expectations are running high that the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan, which meet over the next week, will announce some form of policy easing as well. But it’s unclear whether either bank will reach a consensus on a sizeable package.

Doubts about fiscal policy

In reality, though, while markets will welcome any assistance that central banks can deliver, it’s questionable how effective monetary policy is in countering demand and supply side shocks like those caused by a global epidemic. Hence, investors have pinned their hopes on fiscal stimulus, which is deemed more appropriate to fight a virus crisis and governments at long last appear to be moving in that direction.

US President Trump promised on Monday a number of tax cut proposals to help workers and companies that are struggling from the economic fallout of the virus. The British and Japanese governments are one step ahead and have already announced specific relief measures for businesses, while the Australian government is expected to unveil its own fiscal stimulus later this week.

Hints of fiscal support have gone some way in calming the market panic, but investors are not completely convinced that policymakers will be able to fulfil their promises. In the United States, the White House – with the 2020 election in mind – wants a more ambitious tax package but the Democrats are likely to block anything that isn’t targeted at softening the impact of the coronavirus. In the euro area, the prospect of fiscal stimulus is even more meagre as politicians are nowhere near to agreeing to a substantive policy response to the virus outbreak.

Dollar downside to continue but bottom may not be far

In the absence of meaningful fiscal policy, the sell-off in stock markets looks set to continue, while safe havens such as the yen, gold and sovereign bonds will enjoy further gains. If though, G7 nations and other advanced economies make good on their pledges, equities might start to see a sustained recovery, and the battered greenback could see its downside come to an end as investors scale back their rate cut expectations for the Fed.

For now, however, given that the Fed has more room to cut than other central banks, the dollar has further scope to depreciate versus its rivals and a drop below the 100-yen mark is a realistic scenario. But while the recent moves seem dramatic and represent a sharp turnaround from the narrative just a few weeks ago, it’s worth pointing out that it won’t require too many cuts to take the Fed funds rate back to zero. Thus, there’s a risk in becoming overly bearish about the dollar, especially as the US economy is still faring much better than its peers.