U.S. Review

Data Look Great, If Only It Were Still February

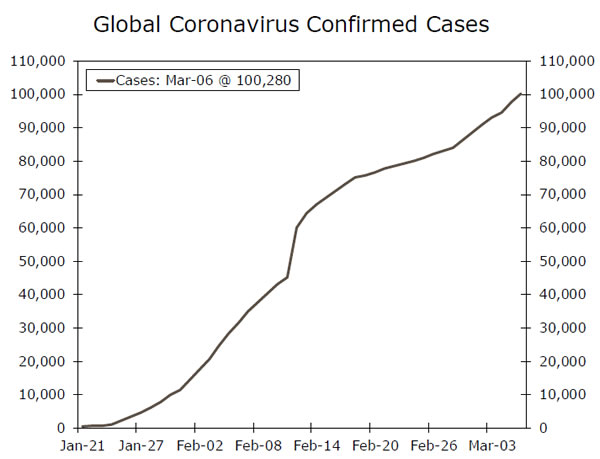

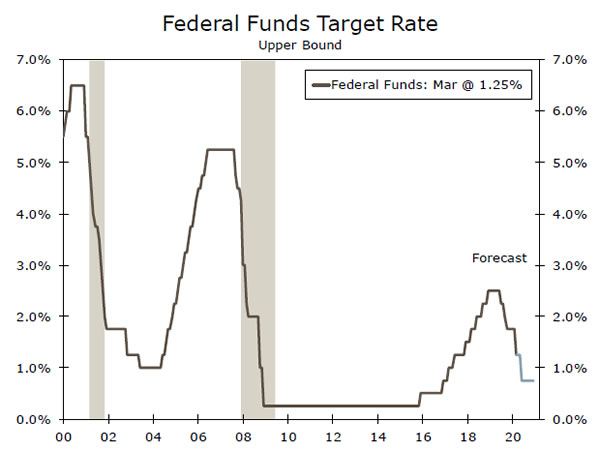

- An inter-meeting rate cut by the FOMC did little to stem financial market volatility, as the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases continued to climb.

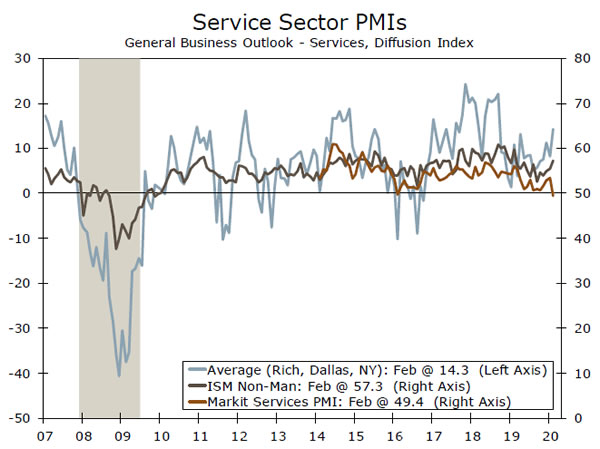

- The ISM manufacturing index narrowly remained in expansion territory, despite some early signs of virus-related supply disruptions, while survey data for the service sector provided conflicting signals.

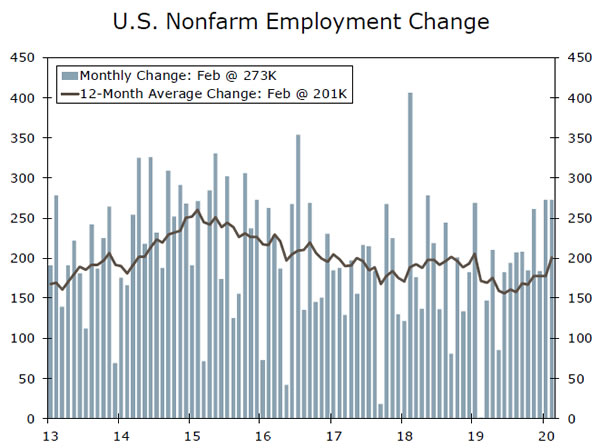

- Friday’s jobs report reiterated the health of the economy in February, with employers adding 273K jobs. The report, however, seems almost stale in the face of the ongoing outbreak.

Data Look Great, If Only It Was Still February

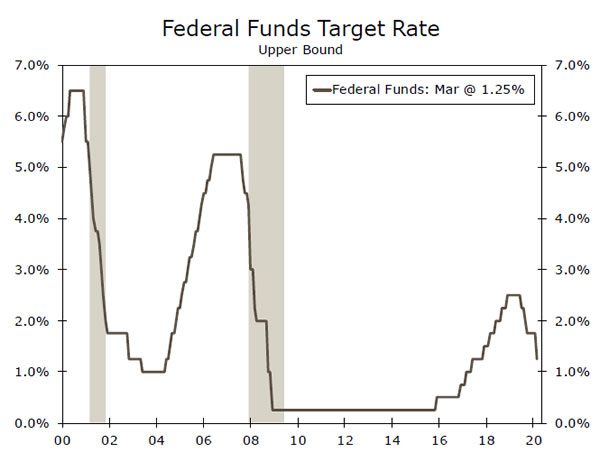

The FOMC cut rates 50 bps on Tuesday, two weeks ahead of their scheduled meeting on March 18 (top chart). The only surprise in this week’s rate cut was the timing, as market participants and our team had anticipated easing. On top of this move, the market is currently priced for almost four more rate cuts by year-end. The extent to which monetary policy can offset the economic impact of the ongoing outbreak, however, remains to be seen. Calls for a fiscal policy response to the coronavirus were only marginally appeased by an emergency spending bill passed in Congress this week (more details on the bill can be found in Topic of the Week). In addition to possible responses from policymakers, the economic outlook remains highly uncertain and dependent on the spread of the virus and efforts taken to contain it.

As for what we can see in the data so far, the week started off with the ISM manufacturing index remaining in expansion territory by a hair. The manufacturing sector had begun to stabilize following a de-escalation in trade tensions at the beginning of the year, but all bets are off now, as February’s report already showed some signs of supply disruptions from the coronavirus. Delivery times rose to a 16-month high, while the imports index fell to a 10-year low and purchasing managers in several industries noted trouble sourcing parts. Normally, supplier setbacks and the rising order backlogs would be inflationary, but prices paid actually dropped 7.4 points on the month, suggesting demand is pulling back. Beyond the virus, lingering issues with Boeing’s 737 MAX also weighed on this month’s report, with one respondent in the transportation equipment industry offering the grim comment, “layoffs are here.”

As for the non-manufacturing side of the economy, February’s ISM non-manufacturing index jumped 1.8 points to 57.3. This increase was at odds with the Markit Services PMI, which turned sharply into contraction territory (middle chart). The two indices are not identical and some of the gap likely comes from strength in mining and construction—goods-producing sectors not included in the Markit Services PMI. Moreover, the Markit Services headline number is based on a single question of whether business activity has improved, and the corollary sub-index in the ISM survey did pull back some in February. Parsing the signs from these two indicators on the health of the service sector will be important going forward, given the sector’s large share of total employment and its exposure to the virus. Companies and consumers are already starting to curtail travel on top of shipping delays that are hitting the transportation sector. Accommodation & food services, entertainment & recreation, retail and arts also stand to take a hit.

Few, if any, of these concerns made their way into Friday’s employment report, however. The strong pace of job growth continued in February with employers adding 273K jobs. Revisions to January and December data brought the average pace of hiring over the past three months up to a robust 243K. While the labor market appears to be in a good place for now, we will have to wait for March data before we can assess the impact of the coronavirus on the U.S. labor market.

U.S. Outlook

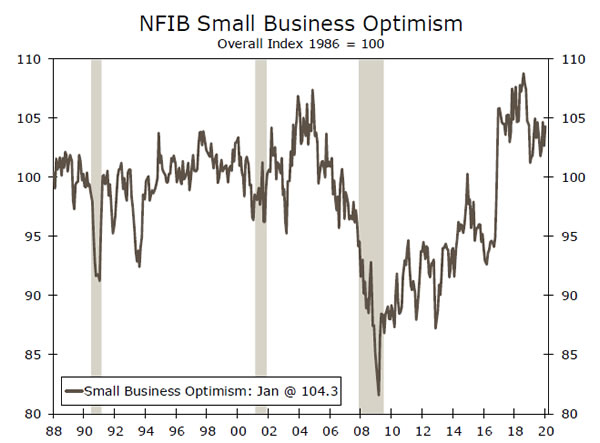

NFIB Small Business Optimism • Tuesday

Sentiment measures will take on increased importance in the nearterm as much of the hard data on activity out in the next few weeks will not capture the most recent developments of the coronavirus. Small business optimism has firmed over the past few months. In January, the index rose 1.5 points, boosted by the rising stock market and signing of the Phase I trade deal with China. With the coronavirus spreading beyond China in February and recent financial market volatility, though, sentiment is likely to have deteriorated a bit in February.

Small business sentiment remains at fairly high levels, but the uncertainty surrounding the coronavirus and the presidential election later this year will likely keep optimism under pressure in the months to come.

Previous: 104.3 Consensus: 102.7

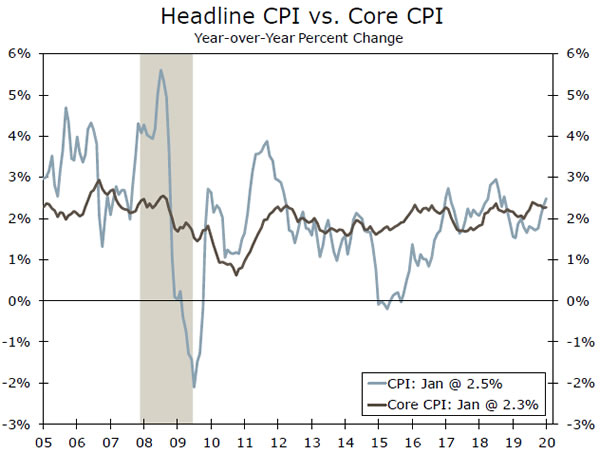

Consumer Price Index • Wednesday

Consumer prices were likely unchanged in February amid an unseasonably large decline in gasoline prices. Excluding food and energy, however, we anticipate prices edged a bit higher in February. While core goods prices are back under pressure now that the initial impact of tariffs has been absorbed, core services inflation remains buoyed by rising costs for housing and medical care.

That said, the overall inflation picture remains rather tame. Falling gas prices point to headline inflation dropping back from the 2.5% year-over-year pace registered in January. Core CPI inflation remains near 2.3% year-over-year, which would typically be consistent with the Fed’s 2% target as measured by PCE, but it has been boosted by a surge in health insurance costs (measured and weighted differently in the PCE deflator). We expect some cooling in core CPI the next few months as inflation expectations have drifted back down toward historic lows.

Previous: 0.1% Wells Fargo: 0.0% Consensus: 0.0% (Month-over-Month)

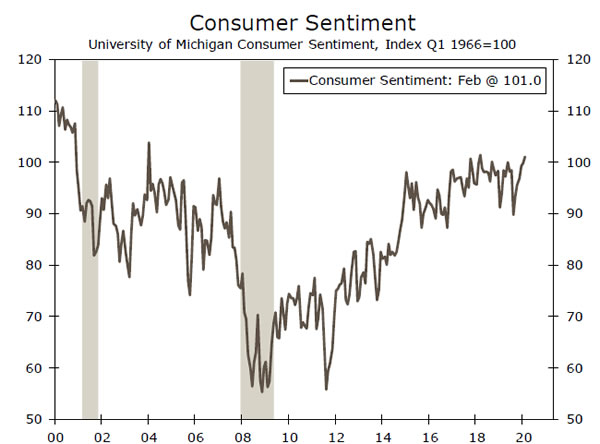

Michigan Consumer Sentiment • Friday

The preliminary March reading of the University of Michigan Sentiment Survey will provide an early look at how consumers are responding to the financial market volatility of recent weeks and spreading of the coronavirus beyond China. The survey will cover interviews from Feb. 26 to Mar. 11, making it one of the most up to date views of recent events.

Heading into March, consumer sentiment had finally broken out of the range registered over 2019. Consumer sentiment climbed to 101.0 in February, as households reported improved views about current and expected economic expectations. The recent market volatility and news of an increasing number of cases in the United States likely reversed that. The degree of change will be closely watched by the Fed ahead of the March 17-18 FOMC meeting to gauge how consumer spending could be affected in the near-term.

Previous: 101.0 Consensus: 96.4

Global Review

Tumultuous Week for the Global Economy

- It was a tumultuous week for the global economy, as concerns continued to grow about the economic and human impact from the spread of COVID-19.

- On Tuesday, finance ministers and central bankers from the G-7 group of nations held a conference call to discuss possible economic policy responses to disruptions caused by the virus.

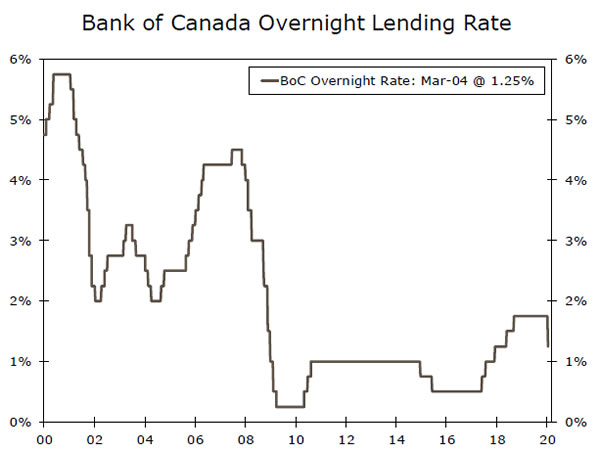

- Outside of the Federal Reserve, only two major developed market central banks took action this week. Both the Reserve Bank of Australia and the Bank of Canada cut their policy rates, by 25 and 50 bps, respectively.

Tumultuous Week for the Global Economy

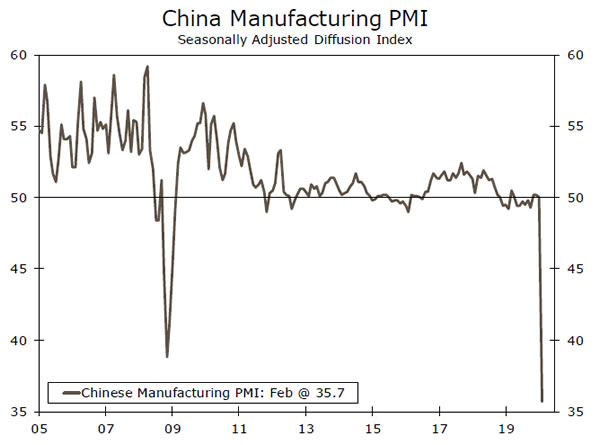

It was a tumultuous week for the global economy, as concerns continued to grow about the economic and human impact from the spread of COVID-19. Some of the very first economic data out of China since the outbreak began signaled a sizable slowdown in that nation’s economy. Purchasing manager indices plunged to record lows (top chart), and Chinese auto sales were down 80% year-overyear in February. Financial markets will be watching closely when hard data on Chinese industrial production, retail sales and fixed investment for the first two months of the year are reported on March 15.

On Tuesday, finance ministers and central bankers from the G-7 group of nations held a conference call to discuss possible economic policy responses to disruptions caused by the virus. Some analysts speculated that the call would yield coordinated monetary and fiscal policy action among the group. The statement released at the end of the call, however, only promised to “use all appropriate policy tools to achieve strong, sustainable growth and safeguard against downside risks.”

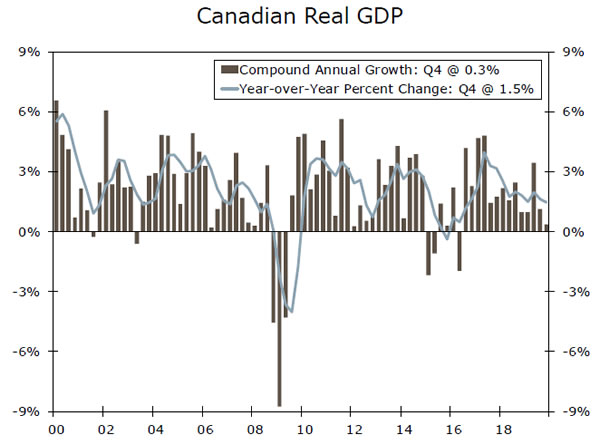

Outside of the Federal Reserve, only two major developed market central banks took action this week. Both the Reserve Bank of Australia and the Bank of Canada cut their policy rates, by 25 and 50 bps, respectively. The RBA judged that the coronavirus outbreak is having a “significant effect” on the Australian economy at present. Similarly, the BoC noted in its policy statement that although Canada’s economy has been operating close to potential with inflation on target, “the COVID-19 virus is a material negative shock to the Canadian and global outlooks.”

The challenge for private analysts and policymakers alike is the difficulty of quantifying the possible economic fallout from the spread of the virus. To a large extent, this reflects the uncertainty about just how much the virus will spread, a near impossible thing to forecast at this point in time. Regardless, some damage has already been done, and in the weeks and months ahead global economic data will likely begin to reflect the ongoing challenges presented by the virus. But just how bad will the deterioration be?

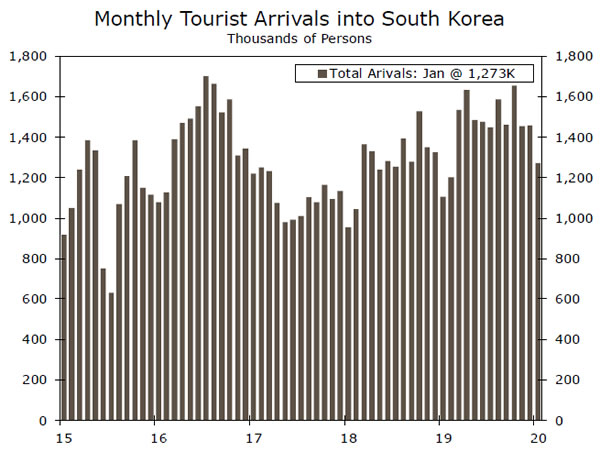

As we wrote in a report this week, in our view, closely monitoring the South Korean economy in the months ahead could offer some useful clues as to how a more widespread outbreak could impact major developed market economies where the disease appears to have arrived later. At present, South Korea has the second most confirmed COVID-19 cases at almost 6,600. South Korea also reports diverse and rich economic data that allow us to examine how certain sectors performed as the number of cases grew from zero to several thousand.

For example, we will receive February data on monthly tourist arrivals into South Korea on March 23 (bottom chart), as well as volume-based service activity indices February data for the hotel and food service and air travel sectors. Based on how these data look when they are reported, it should give us a better feel for how the economic data will look in other countries that currently are or could in the near future be struggling with their own outbreaks.

Global Outlook

Brazil Industrial Production • Tuesday

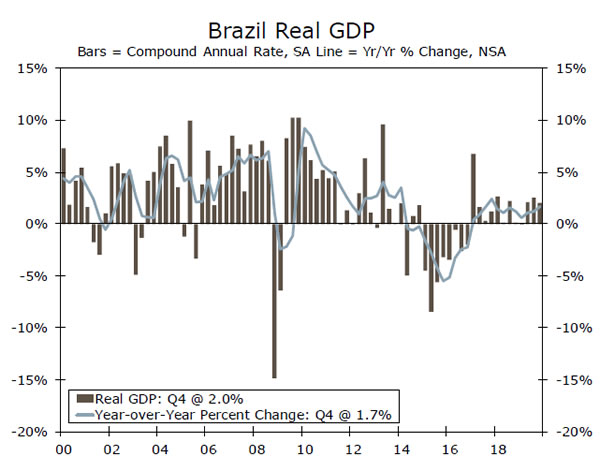

The Brazilian economy continues to trudge along, with economic growth meandering along at a 1-2% pace. The deep recession in 2015-2016 and subsequent weak recovery have led monetary policymakers there to continuously ease policy. The central bank has cut its main policy rate 225 bps since last summer, and by a total of 10 percentage points since October 2016. At present, real short-term interest rates in Brazil are the lowest they have been in decades, and this has done the currency no favors. The Brazilian real has depreciated by nearly 16% against the dollar this year.

The industrial production data reported next week will be for January, thus giving markets a baseline for how factory sector output in Brazil was performing before the global COVID-19 took hold. With diminished monetary policy ammunition and an already weak economy, a sharp slowdown in global growth would not bode well for the Brazilian economy.

Previous: -1.2% (Year-over-Year)

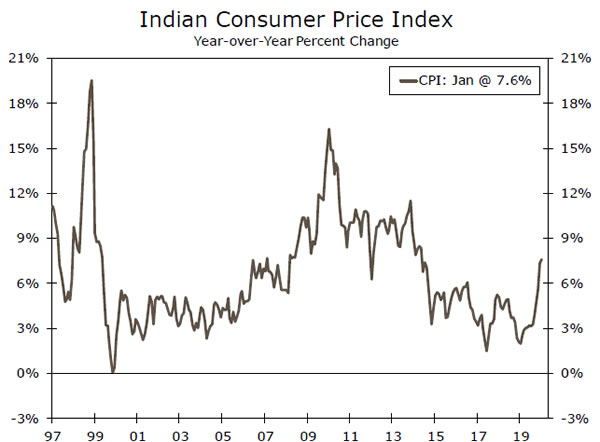

India CPI • Thursday

Inflation in India has skyrocketed over the past few months, with the year-over-year growth in the consumer price index reaching a pace not seen since 2014. Food and beverages account for nearly half of the CPI in India (in comparison, this category accounts for about 14% in the United States), and inflation in this category can be highly volatile. The most recent spike in headline inflation can be attributed to higher food prices, particularly for onions. Excluding onions, headline inflation would have been about 2 percentage points lower.

Despite the much higher inflation, the monetary policy committee of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) held rates steady at its meeting on February 6, and promised to maintain the accommodative stance of policy “as long as it is necessary to revive growth.” The RBI expects food price inflation, and thus overall inflation, to recede later this year. Markets are priced for roughly 60 bps of additional policy rate easing by the RBI over the next year.

Previous: 7.6% Consensus: 6.7% (Year-over-Year)

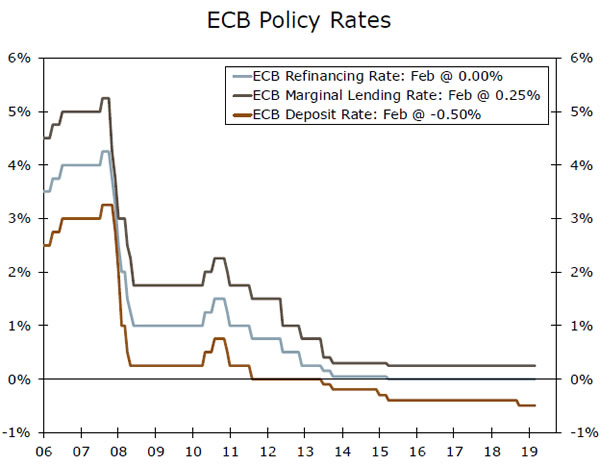

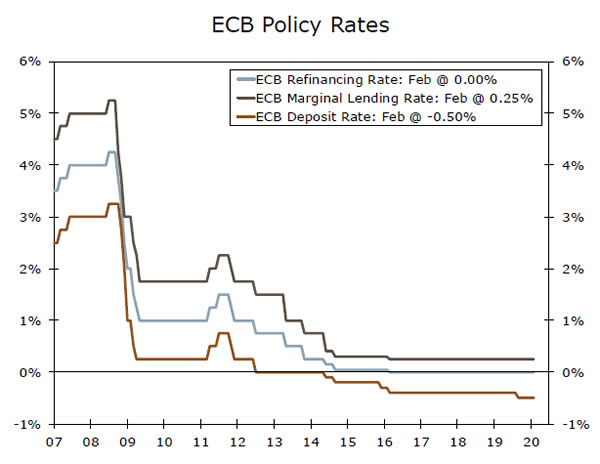

European Central Bank Meeting • Thursday

Unlike the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank (ECB) has thus far refrained from taking decisive action to combat a possible economic slowdown from the spread of COVID-19. To an extent this makes some sense, as the ECB appears to have grown increasingly uncomfortable with the idea of venturing deeper into negative interest rate territory. And since the central bank is already purchasing sovereign bonds through a quantitative easing program, additional easing options are relatively limited.

It seems likely that the ECB will make the terms of the next round of targeted long-term refinancing operations (TLTROs) more favorable. Other than that, we do not anticipate any additional monetary policy easing at next week’s meeting, though we do expect that the ECB will eventually have to resort to additional rate cuts. We look for the deposit rate to end Q2-2020 20 bps below the current -0.50%.

Previous: -0.50% Wells Fargo: -0.50% Consensus: -0.50% (Deposit Rate)

Point of View

Interest Rate Watch

Global Monetary Easing Underway

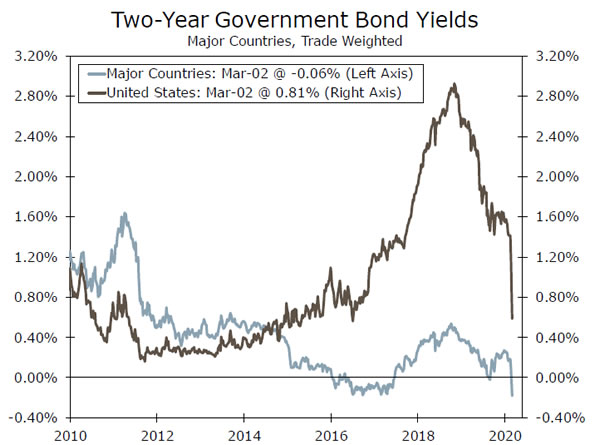

The Federal Open Market Committee cut its target range for the fed funds rate 50 bps on March 3. As we noted in a report we wrote that day, only the timing of the rate cut was a bit of a surprise, coming as it did before the next scheduled FOMC meeting on March 18. Given the risks that the COVID- 19 outbreak poses to the U.S. economy, we were forecasting that the FOMC would cut rates 100 bps by the end of the second quarter (top chart). We maintain that view, although we readily acknowledge that the exact timing of the remaining 50 bps of rate cuts remains uncertain. The committee has scheduled policy meetings on March 18, April 29 and June 10.

The Bank of Canada (BoC) cut its main policy rate 50 bps at its regularly scheduled meeting on March 4 (middle chart), which was 25 bps more than the market consensus had anticipated. Real GDP growth in Canada has lost momentum over the past year or so, and the marked decline in oil prices since the beginning of the year will impart a slowing effect on the Canadian economy. As we wrote in a recent report, we look for the BoC to cut at least an additional 25 bps between now and the end of Q2.

The Bank of England (BoE) holds its next policy meeting on March 26, and we suspect that policymakers will opt to cut rates 25 bps at that meeting. That said, there is some uncertainty regarding the monetary policy outlook in the United Kingdom because it will be the first policy meeting that will be chaired by incoming Governor Andrew Bailey. (Mark Carney will end his term as Governor on March 15.)

Whereas the Fed, the BoC and the BoE all have conventional policy space (i.e., rates are above zero), the European Central Bank has limited conventional “ammunition.” As shown in the bottom chart, the ECB’s deposit rate currently stands at -0.50% and its main refinancing rate has been maintained at 0% for nearly four years. That said, we look for the ECB to cut its deposit rate another 10 bps in the coming months, more likely in April than in March. The ECB could also ramp up its pace of QE bond purchases.

Credit Market Insights

Tumultuous Times in Corporate Credit

In light of the Fed’s 50 bps emergency rate cut and the 10-year UST yield falling below 1.0%, an intensification of recession fears has swept through the markets. Indeed, the past several weeks have proven tumultuous for corporate credit as spreads gapped wider on escalating concerns over the COVID-19 outbreak and the increasing likelihood of a global growth slowdown.

This week has been one of two halves. Initially markets were frozen by risk aversion initiated by the coronavirus. Following the Fed’s rate cut, activity surged as many companies rushed supply to market to take advantage of an improvement in sentiment. Investment Grade fund flows reversed, with $1.1 billion in outflows, marking the first weekly outflow since January 2019. High Yield fund flows decelerated on the week with $2.7 billion in outflows. In regards to spreads, IG widened 13 bps week-over-week to 128 bps, with yields declining 20 bps to 2.3%. HY spreads widened 34 bps week-over-week to 494 bps, with yields falling 10 bps to 5.9%.

Market participants are now keenly focused on the adverse impacts of the coronavirus on corporate activity, earnings, and debt risks–reflecting the loss of economic production and the threat of supply chain dislocation. Looking ahead, the direction of corporate credit spreads appears to depend heavily on the ability of government officials and the medical community to contain and remediate the escalation of the coronavirus.

Topic of the Week

Congress Agrees to $7.8 Billion for Virus Fight

This week, Congress passed a $7.8 billion supplemental appropriations bill to provide additional funding for fighting the COVID-19 outbreak that has reached the United States. The funding goes towards a variety of policy goals, such as money for the development of vaccines or the acquisition of medical equipment.

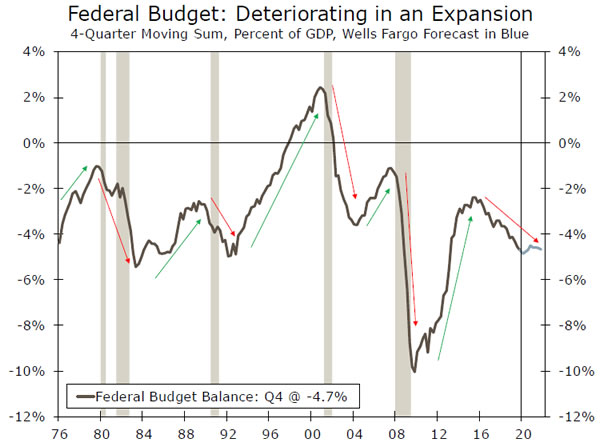

While this bill may improve public health outcomes, it should not be thought of as a stimulus for the U.S. economy. The federal government is expected to spend roughly $4.6 trillion in FY-2020, so the $7.8 billion authorized this week is merely a drop in the bucket. Our federal budget deficit forecast already had built in some wiggle room for occurrences like these. Rarely does a year go by where there are not a few emergency appropriation bills for things like hurricanes, earthquakes or other unforeseen circumstances.

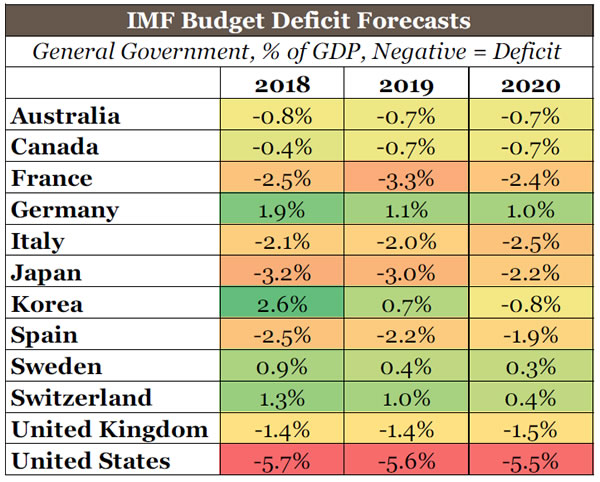

Some research analysts, policymakers and media outlets have mentioned the possibility of a more standard fiscal stimulus, such as an infrastructure plan or a payroll tax cut, to spur faster economic growth. While the situation may eventually warrant such a plan, Congress has not yet shown a serious appetite for stimulus of that size and scope. The United States is already running relatively loose fiscal policy, both relative to its developed market peers (top chart) and relative to history (bottom chart). That said, more fiscal stimulus is certainly possible in the near term, especially as U.S. Treasury yields have reached all-time lows.

A challenge to any fiscal stimulus response will lie in the design of the program. If a decline in aggregate demand occurs due to less air travel, going out to eat, etc., it is not immediately clear that something like a payroll tax cut would spur people to resume these activities. Efforts to provide relief to businesses may do more to forestall layoffs or defaults in the highly leveraged corporate sector, but these types of measures would likely not be as politically popular as direct consumer relief, an important reality in a presidential election year.