Executive Summary

As concerns continue to grow about the economic impact from the spread of COVID-19, analysts have struggled to get their arms around the possible fallout. To a large extent, this reflects the uncertainty about just how much the virus will spread, a near impossible thing to forecast at this point in time. Regardless, some economic damage has already been done, and in the weeks and months ahead global economic data will likely begin to reflect the ongoing challenges presented by the virus. But just how bad will the deterioration be?

Given that the outbreak began in China, it makes sense that a weakening in the economic data would first show up in China. Indeed, we have already begun to see this, as February PMI data in China were extremely weak, and auto sales in the nation were down 80% year-over-year in February. That said, China may not be the best benchmark for assessing the potential slowdown elsewhere in the world. China’s economic data are generally not nearly as detailed or reliable as figures found in most developed market economies. Furthermore, China continues to have the overwhelming majority of global cases of COVID-19, and has taken the most drastic public health policy steps to combat the virus. Thus, while monitoring Chinese economic data in the months ahead will of course be important for financial market participants, it may not offer much in the way of clues for how a broader outbreak could impact the economic performance of a country like the United States.

If not China, which country might offer the best first look at how the virus is impacting industries like manufacturing, air travel and dining out? In our view, closely monitoring the South Korean economy in the months ahead could offer some useful clues as to how a more widespread outbreak could impact major developed market economies where the disease appears to have arrived later, such as the United States. At present, South Korea has the second most confirmed COVID-19 cases at roughly 6,000. South Korea also reports diverse and rich economic data that allow us to examine how certain sectors performed as the number of cases grew from zero to several thousand.

Of course, the comparison between the South Korean economy and another like the United States is not perfect. South Korea is significantly more exposed to external demand, for example, and private consumption accounts for about 20 percentage points less of Korean GDP than it does in the United States. And the policies adopted in response to the virus, such as quarantines or travel restrictions, are likely to vary between any two countries, which in turn can create different economic outcomes. That said, given the unchartered territory in which the world economy currently finds itself, in this report we examine a handful of different economic indicators in South Korea we will be keeping an eye on going forward. Then, as new data on these indicators are released, we will update our analysis one to two months from now and assess what it may be able to tell us about economic data deterioration elsewhere in the world.

First, a Bit about the South Korean Economy

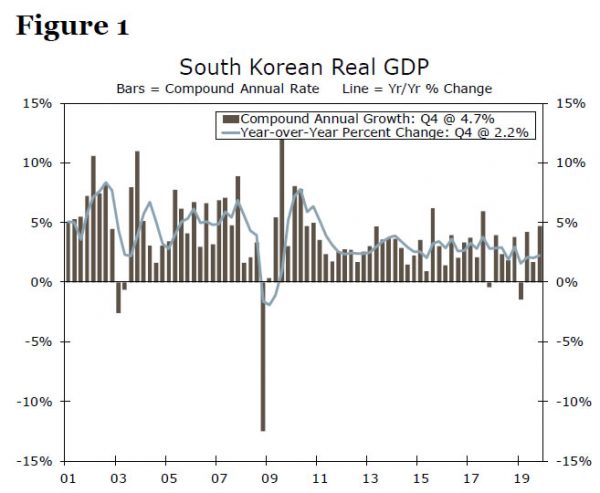

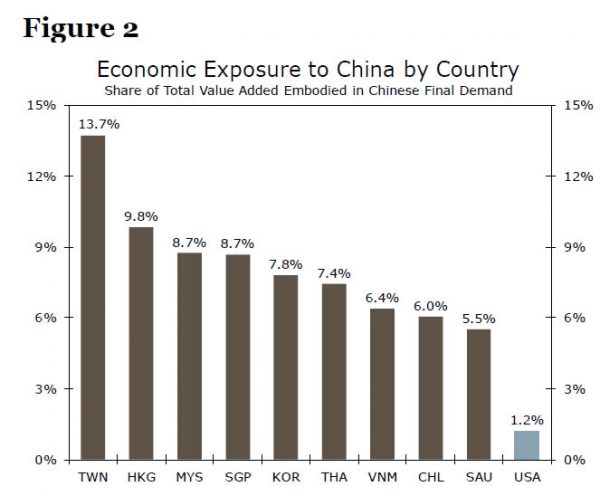

South Korea’s economy is the 12th largest in the world as measured by nominal U.S. dollars, and 14th when adjusted for purchasing power parity. The country is relatively open and export-oriented, with exports accounting for approximately 40% of GDP (the comparable figure in the United States is roughly 12%). Economic growth in Korea has softened over the past couple years (Figure 1), primarily as exports and investment have decelerated amid the trade war between the United States and China. As we noted in a recent report, South Korean output is relatively exposed to an economic slowdown in China: nearly 8% of total value added in South Korea is embodied in Chinese final demand (Figure 2). Perhaps unsurprisingly, private gross fixed capital formation in Korea declined 6.1% in 2018 and 3.1% in 2019. Against this backdrop, policymakers have taken actions to try and shore up the economy. The central bank cut its main policy rate 50 bps in 2019, and fiscal policymakers have enacted stimulus to boost growth. Government consumption expenditures were up 6.6% year-over-year through Q4-2019, and government investment rose an even more robust 16%.

The central bank met on February 26 to discuss the outlook for monetary policy. At that point in time, there were 977 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the country. Monetary policymakers elected to keep the main policy rate unchanged, and in the economic outlook report the central bank judged that “after a temporary slowdown due to the negative impacts from COVID-19, the domestic economy is expected to recover as private consumption and exports rebound amid continued fiscal expansion and a recovery in facilities investment.” Since then, the situation has deteriorated further, as the number of cases has continued to climb, reaching more than 5,600 as of this writing. In the next section, we examine some key economic indicators for the South Korean economy that we believe will help provide a benchmark for the impact a COVID-19 outbreak could have on different sectors of an economy.

What Should We Be Watching in the Weeks Ahead?

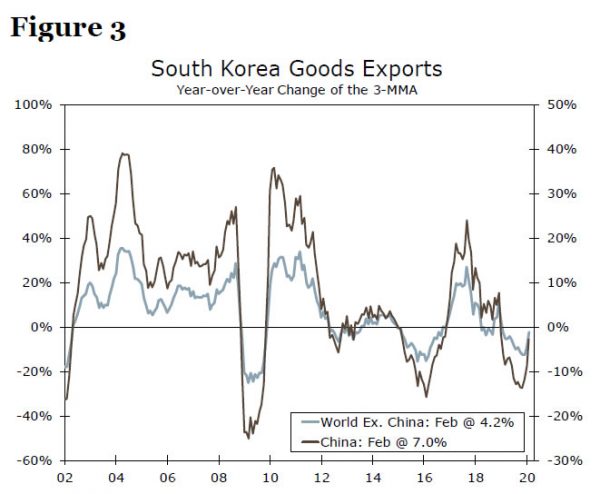

Given the importance of external demand, particularly from China, to the South Korean economy, the magnitude of a contraction in exports will be critical to the performance of South Korea’s economy. Exports rose on a year-ago basis in February, though this was aided by the timing of the Lunar New Year holiday, which resulted in three extra working days.1 We will be watching closely to see to see the extent to which this improvement reverses itself when preliminary data for March are released on March 31.

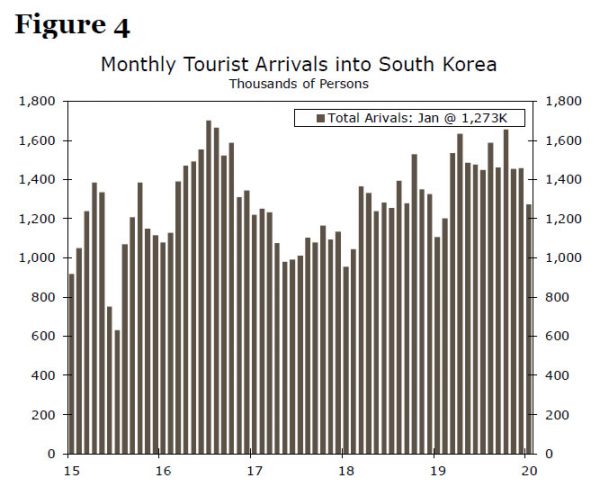

Along a similar vein, South Korea reports monthly tourist arrivals into the country on a monthly basis. When tourists visit a country, their expenditures are considered “exports” to the country they are visiting. There were 1.3 million tourist arrivals in South Korea in January, 38% of whom came from China (Figure 4), and February data will be reported on March 23. The drop-off in visitors both from China and the rest of the world will provide an initial sign of what other countries might experience, should they see a similar outbreak.

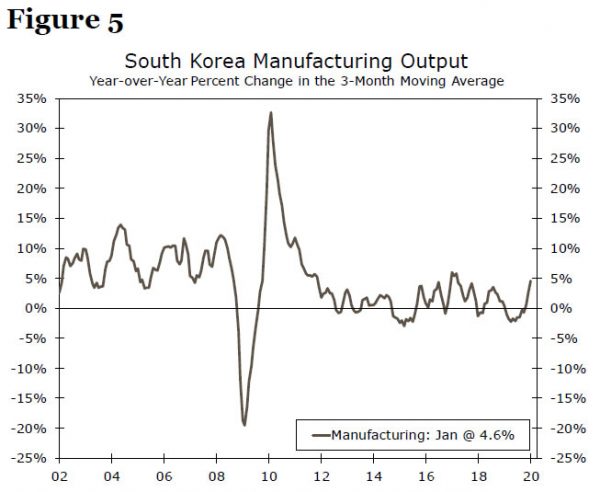

Manufacturing output in South Korea had also begun to rebound over the past few months. The year-over-year percent change on a three-month moving average basis reached a nearly three year high in January (Figure 5). Factory sector output comprises roughly 25% of overall GDP in South Korea, which is about the double the share in the United States. Thus, similarly sized contractions in the South Korean and U.S. manufacturing sectors would likely exert a bigger drag on economic growth in Korea than in the U.S., all else equal. The February data for this indicator will be released on March 30. A material deterioration going forward would offer additional evidence that the green shoots seen in the global economy pre-coronavirus have been paved over. The PMI for February, which dropped 1.2 points to 48.7, suggests the manufacturing sector may already be feeling some effect from the virus.

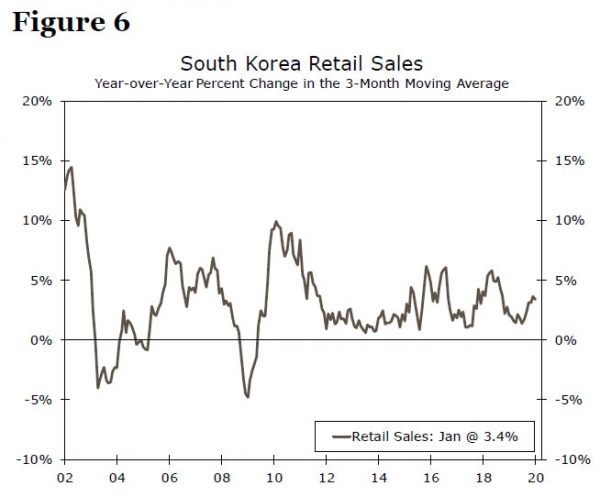

On the consumer side, Korean retail sales have also shown some improvement of late (Figure 6). Consumption is a much smaller portion of the Korean economy than it is in the United States, so a noticeable slowdown in Korean retail sales as a result of the COVID-19 outbreak would not portend well for U.S. economic growth, should the U.S. see a similar outbreak. February retail sales data for Korea are reported on March 30.

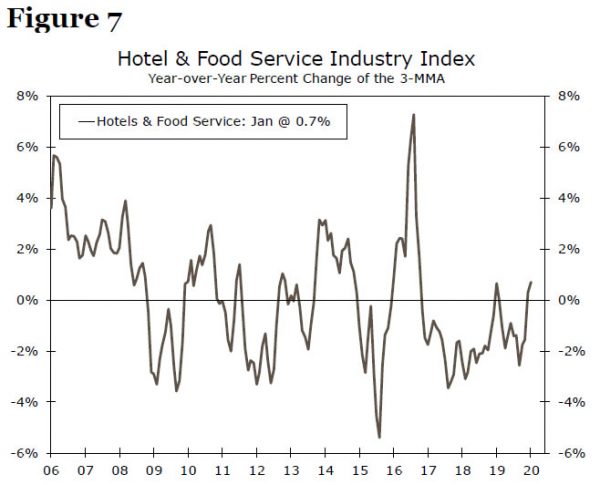

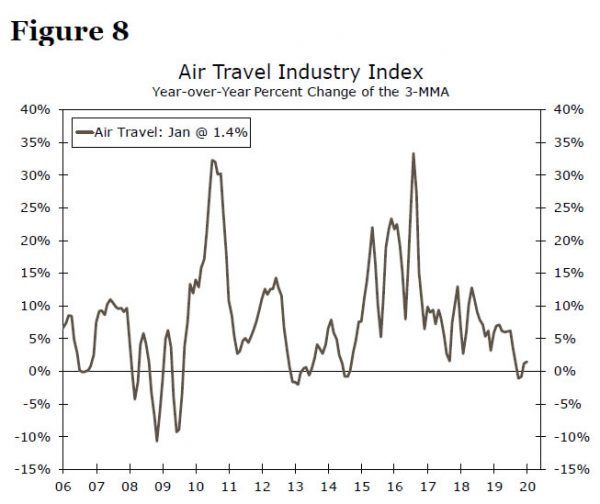

Within the consumer sector, accommodations and food services and passenger air transport are two areas we see as particularly at risk to a downturn from the outbreak. The South Korean government produces a volume-based service activity index for a host of different service sector activities, including the two listed above. Even before the virus began to take hold, output growth in these two sectors of the economy was relatively weak (Figures 7 and 8). Again, it is worth reiterating that, unlike exports, these more consumption-oriented segments of the Korean economy are less important to economic growth than they are in the United States. Food services and accommodations account for roughly 2.6% of Korean output, for example, compared to 4.8% in the United States. Thus, a similarly sized contraction in this sector in each of the two respective economies would be more damaging to U.S. economic growth than Korean growth, all else equal. The February activity indices for accommodation and food services and passenger air transport will be released on March 31.

Conclusion: Monitoring the Data Closely in the Weeks Ahead

After China, South Korea has seen the most severe COVID-19 outbreak thus far. This outbreak in South Korea appears to have started before the disease began to spread in several other major advanced economies, such as the United States. As a result, it would not surprise us if the economic data in South Korea begin to show the effects of the virus a bit before they do in the United States. In the weeks and months ahead, we will be monitoring the South Korean economic data closely to assess the damage. As mentioned previously, weakness in areas like exports and manufacturing would likely be more damaging to the South Korean economy than the U.S. economy, at least on a relative basis. Conversely, material weakness in consumption-oriented categories like accommodations and food services would be more damaging to U.S. economic growth, all else equal. As new data on these indicators are released, we will update our analysis one to two months from now and assess what it may be able to tell us about economic data deterioration elsewhere in the world.

1 There were three less working days in 2019 than in 2020 because the Lunar New Year was celebrated in February last year. The holiday occurred in January this year.