Executive Summary

- The Eurozone economy was already at risk amid the coronavirus due to its trade exposure to China, but the latest outbreak in Italy only adds to those risks. Fortunately, sentiment data were relatively encouraging in the beginning of Q1 and prior to the Italian outbreak, suggesting all is not lost for Eurozone Q1 GDP.

- Reports of German fiscal stimulus are encouraging, but not a guarantee that authorities will deliver. Moreover, our calculations suggest the boost to GDP from the stimulus that has been reported would be modest, but could offset some of the virus hit to growth.

Europe on Shaky Footing Even Before Virus Hit

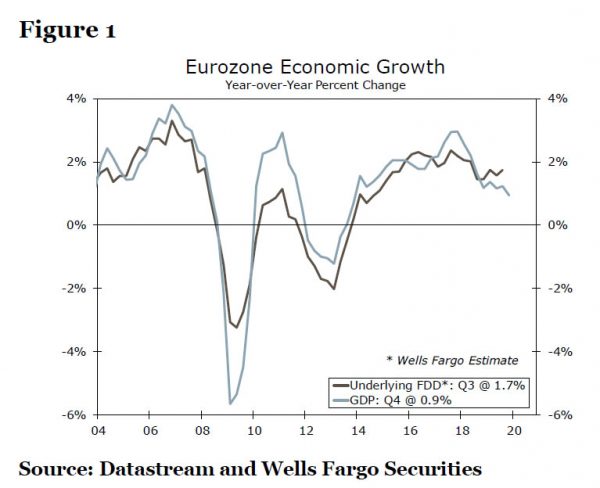

The Eurozone economy has had a rough go of it over the past year or so, as real GDP growth slowed to just 0.9% year-over-year in Q4-2019. To be sure, domestic demand generally held up better throughout much of last year, but we do not have those figures for Q4 yet, and the initial evidence suggests underlying domestic demand took a significant hit in Q4 as well (Figure 1). Meanwhile, just as the region was digging out from its slowest year of growth since the European Debt Crisis, the coronavirus outbreak has emerged as a significant threat to the Eurozone’s nearterm growth prospects.

Fortunately, the initial economic data were at least somewhat positive for the first few weeks of the year. The services PMI edged higher to 52.8 in February, while the manufacturing PMI jumped to 49.1. There are, however, two caveats with these data points. First, these figures were collected prior to the most recent surge in cases in Italy, which is likely to lead to some downward revisions when these data are updated next week. Second, the rise in the manufacturing PMI was partly due to an increase in supplier delivery times, which is usually a sign that suppliers cannot keep up with demand, but in this case was probably more reflective of global supply chain disruptions from coronavirus. Still, with those caveats in mind, other components of the services and manufacturing PMIs also rose, including new orders and output. Meanwhile, consumer confidence climbed to -6.6 in February, the highest level since September.

Still, the latest coronavirus developments are likely to significantly disrupt Eurozone economic activity over the next few weeks. The number of cases in Italy has surged in recent days to 400 and has yet to show signs of slowing, while new cases in Spain and Greece are fueling concerns of a broader contagion. Parts of Northern Italy are on partial lockdown, and after the country already registered a 0.3% quarter-over-quarter decline in real GDP in Q4-2019, a technical recession is very much a possibility. Italy represents around 15% of Eurozone GDP, so a decline in Italian GDP does not automatically imply a decline in GDP for the region as a whole, but it will clearly be a headwind.

Of course, the effects of coronavirus on the Eurozone economy will largely depend on what happens next. Most of the rest of the region, including France and Germany, which combined account for around half of Eurozone GDP, have not seen any surge in new cases of the virus. It is hard to get an exact estimate due to several methodology changes, but data on new cases from Hubei—the source of the outbreak—suggest it took authorities around two weeks to get the growth in new cases under control. Assuming a similar timeframe in Italy, and adding a two-week buffer to resume normal economic activity, we think it is reasonable to say that the disruption could largely pass by the end of Q1.

For now, we have 0.2% quarter-over-quarter real GDP growth penciled in for the Eurozone in Q1, which already incorporates the disruptions to Chinese and global demand prior to the recent spike in Italian cases. Recent developments in Italy suggest that Eurozone Q1 real GDP growth could be closer to 0.1% quarter-over-quarter, although we are not at this point making any changes to our forecast until we see how the situation evolves from here. If there is contagion to other core countries such as Germany and/or France, then the risk of an outright decline in Eurozone GDP in Q1 could become a more realistic prospect.

How Will Policymakers Respond?

Amid the outbreak, European Central Bank (ECB) policymakers have generally not signaled any change in its relatively neutral stance. Comments from policymaker Villeroy summed up the situation well, in our view, as he noted that monetary policy space is limited, and in any case was not the right policy response given the coronavirus is more of a supply shock. Accordingly, policymakers have reiterated calls for fiscal stimulus, as they have for several years now. Those requests have generally fallen on deaf ears, as Germany in particular has signaled a lack of appetite for fiscal stimulus.

More recently, however, reports have indicated that German Finance Minister Olaf Scholz may temporarily ease the “debt brake” that restricts the German government’s ability to run budget deficits. These reports are unconfirmed and short on details, but indicate the measures could be focused on local government spending and be worth around €20 billion, or around 0.5% of annual German GDP. Assuming a fiscal multiplier of around 0.5, and considering Germany accounts for roughly 30% of Eurozone GDP, a fiscal stimulus of this size could boost annual Eurozone GDP by roughly 0.1-0.2 percentage points.1 This suggests that our estimate for 2020 full-year GDP growth of 1.0% in the Eurozone may not be too far off the mark, as a hit to growth from the virus outbreak in the short term could be at least partly offset later in the year by a modest stimulus boost.

However, it is far from a sure thing that these reports of stimulus will turn into actual stimulus action. As stated by German law, a majority of members of the Bundestag (German Parliament) must approve of such measures, while members must also approve a plan to reduce extraordinary borrowing within a reasonable time frame. In short, approving German fiscal stimulus is a steep hill to climb, and we would caution against over interpreting recent reports of stimulus as a sign that more fiscal spending is a sure thing.

1 “Fiscal Multipliers: Size, Determinants and Use in Macroeconomic Projections.” Batini, N., L. Eyraud, L. Forni and A. Weber. September 2014. IMF Technical Notes and Manuals.