The novel coronavirus, COVID-19, continues to spread, heightening concerns about the impact on global supply chains that have become significantly more integrated in recent decades.

We continue to believe Canada won’t experience the same level of travel-related disruptions it saw during the SARS epidemic in 2003 absent a more significant outbreak domestically. However, the risk of supply-chain disruptions — something that didn’t generate a noticeable drag on the economy at the time of SARS — is larger now than it was then.

China appears to be getting a handle on the outbreak, and the other regions most impacted by the virus represent a small share of direct Canadian production input supply. The longer the outbreak lasts, and the further it spreads, the more impact intermediate-goods shortages could have on industrial output in Canada. At this point we still see that possibility as more of a downside risk than a best base-case assumption.

Key points:

- Direct risks of supply-chain disruptions related to COVID-19 are larger than at the time of the SARS outbreak

- About 10% of Canadian imports of intermediate products come from China, 4% from South Korea, Italy and Japan combined

- Another risk to Canada’s economy would be spillovers from disruptions hitting the US industrial sector

- COVID-19 adds to growing list of negative factors, along with slower underlying growth trends, the Bank of Canada is eyeing

Canadian direct supply-chain exposure not insignificant, but still limited

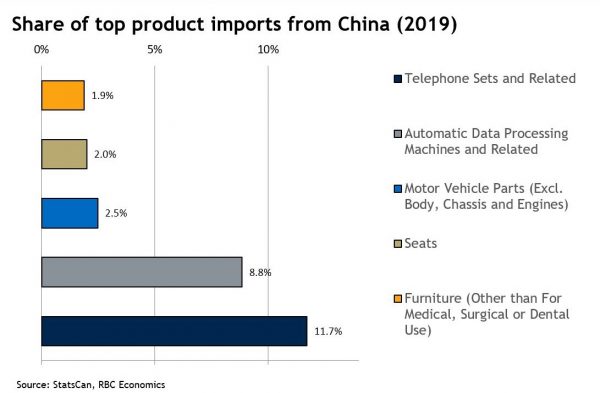

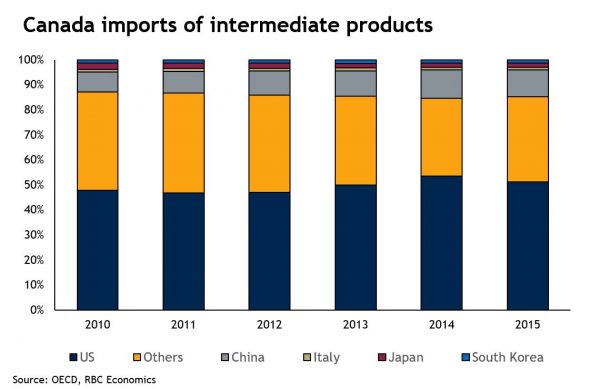

Of the regions worst-hit to-date by COVID-19, China is by far the most significant import source for Canada. Yet much of Canada’s imports from China are finished goods (notably cellphones), which have limited impact on near-term domestic production. Imports of intermediate inputs matter more for production, and about 10% of total Canadian imports of intermediate products came from China at last count (OECD data from 2015). That easily makes China Canada’s second-largest source of imported production inputs. But the share is still small compared to the 50% of the total accounted for by the U.S.

Canadian intermediate exposure to regions outside of China most impacted by COVID-19 is limited. South Korea, Italy, and Japan together account for about 4% of total intermediate product imports. And efforts in China (the larger supplier) to contain the outbreak have reportedly gained traction. From that perspective, it is not clear the spread of the virus outside of China has substantially increased go-forward supply-chain risks for the Canadian economy on net.

Indirect exposure via ties to the US

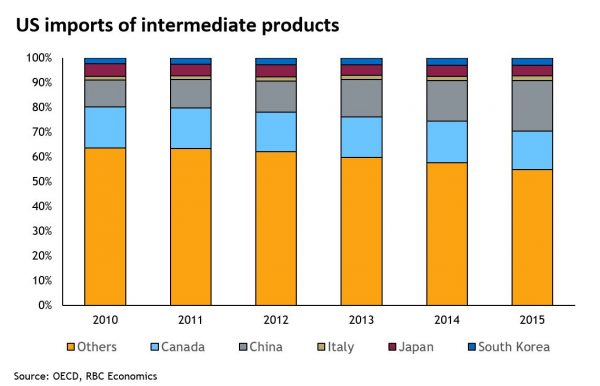

The regions hit by more significant COVID-19 outbreaks all represent a larger share of US intermediate product imports than in Canada. China accounts for about 20%, while Italy, South Korea, and Japan combined account for about 10%. As a less trade-exposed economy, the US is able to source a larger share of inputs domestically — US intermediate goods imports are roughly 7% of GDP, versus 17% in Canada. But the softening in US industrial output last year as US-China tariffs ramped up made clear that the US industrial sector is still vulnerable to disruptions in parts supplied from abroad. Since Canadian industry is tightly integrated with the US, there would be some spillovers for Canadian manufacturers should US manufacturers be significantly impacted.

Service-sector less exposed, for now

Much of the economic impact in regions hit significantly by the outbreak will likely come from the domestic service sector as fear of catching the virus, or mandated/encouraged quarantines, hamper household spending. In China, people are reportedly still staying closer to home despite the government encouraging a return to work in most regions. That will undoubtedly leave a significant impact on the more domestically focused service sector, but that disruption also has less implications for global growth because service-sector activity is less trade-sensitive. In Canada, 70% of the economy and 80% of employment is accounted for by service industries. A significant spread of the disease within Canada would keep more people at home. But with a relatively small number of cases (11 at last check, 6 of which have already recovered), we are not yet close to that point. And the bulk of Canadian service-sector activity is significantly less exposed, at least in the near-term, to external growth risks.

BoC looks increasingly likely to cut rates

COVID-19 disruptions are just the latest in a growing list of events weighing on Canadian growth in recent quarters, including rail disruptions linked to last fall’s CN Rail strike and anti-pipeline protests more recently. Rail disruptions have eased but not disappeared. A more pressing implication for the Bank of Canada may be that, even after subtracting the drag from ‘transitory’ factors from growth in Q4 (which combined to roughly half a percentage point drag), the economy still probably grew less than 1% in the quarter. We continue to expect the central bank to cut rates by 25 basis points in Q2, which aligns with market pricing. Markets are pricing in another full cut by the end of the year.