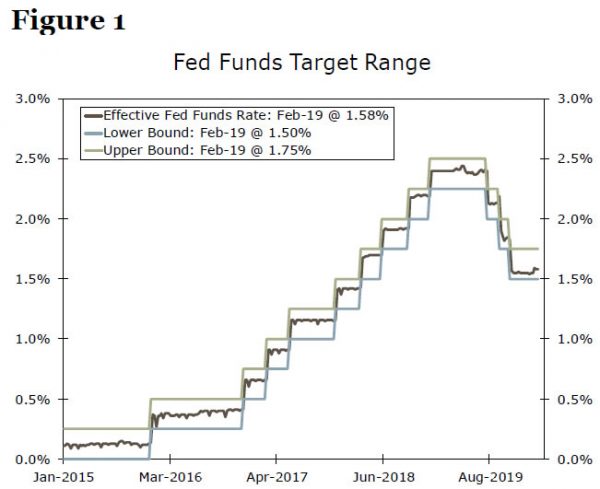

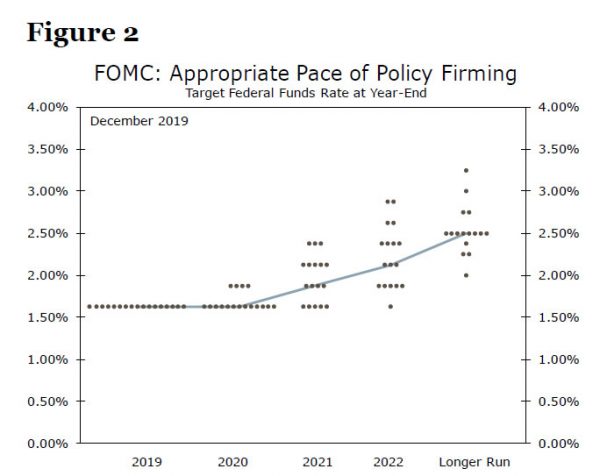

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), which cut rates 75 bps in 2019, has kept its target range for the fed funds rate unchanged at 1.50% to 1.75% since October (Figure 1). Moreover, the so-called “dot plot” suggests that most committee members believe that it would be appropriate to keep the target range unchanged throughout 2020 (Figure 2). However, the rapid spread in recent days of COVID-19 to countries other than China has led market participants to the conclusion that the FOMC will be forced to ease policy. As of this writing, the market is fully priced for a 25 bps rate cut by the June 10 FOMC meeting and another 25 bps rate cut by the November 5 meeting. Will the Fed cut rates?

The mantra coming out of the Fed in recent months has been that the current stance of monetary policy will remain appropriate as long as there is not a “material” change to the economic outlook. In that regard, the “central tendency” of FOMC members’ forecasts sees U.S. real GDP growing roughly 2% between Q4-2019 and Q4-2020 (Figure 3).1 In terms of PCE inflation, the FOMC’s preferred measure of consumer price inflation, the central tendency for 2020 is just below 2% (Figure 4). So what would constitute a “material” change to the Fed’s economic outlook?

The FOMC does not make its forecasts of quarterly GDP growth publicly available. But our GDP growth forecast for 2020 is roughly similar to the FOMC’s projection as we look for real GDP to grow 2.1% on a Q4-to-Q4 basis in 2020.2 Consequently, the FOMC’s quarterly growth forecasts for 2020 are probably roughly similar to our own. We currently look for real GDP to grow at an annualized rate of only 1.5% in the first quarter of 2020 before rebounding to growth rates of 2.3% and 2.4% in the following three quarters. Thus, the FOMC would likely need to see evidence that the economy was growing “materially” slower than these growth rates to induce it to cut rates.

But the Fed will not see much evidence for some time. Looking ahead, the ISM manufacturing index for February, which is slated for release on March 2, will be an important benchmark to judge the current state of the American manufacturing sector. But the March 2 release probably will be too early to see much evidence of potential supply chain disruptions in the manufacturing sector. Therefore, the Fed probably will need to wait until the regional PMIs and the following ISM index print in mid-March to early April, at the earliest, to see evidence of supply chain disruptions. The evidence probably will not show up in “hard” data until later.

Unless financial markets completely go into a tailspin between now and mid-March, which would imply a marked tightening in financial market conditions, the FOMC likely will stand pat at the March 18 FOMC meeting. That said, the committee could signal on March 18 its intentions to ease policy later in the year by explicitly stating that the risks to its GDP growth forecast are skewed to the downside. The “dot plot,” which will be updated at the March meeting, will also be important in judging the FOMC’s intentions. The committee could potentially cut rates at the April 29 meeting, but will it have enough evidence by late April to suggest that a “material” change to its economic outlook is warranted?

In our view, June 10 is the most likely date for a rate cut, should the FOMC eventually elect to ease policy. By early June the committee will have economic data for much of the second quarter that will help it determine whether a change to its outlook is warranted. If the committee decides that it needs to ease policy, then it seems likely that it will end up cutting rates by more than 25 bps in total. The FOMC has had six easing cycles in the past thirty years, and each time the committee cut rates by at least 75 bps over the course of the easing cycle. This year, the November 3 election introduces some interesting complications. Everything else equal, the committee would prefer to remain on hold in the fall of a presidential election year so as not to be seen as tipping the scales in one direction or the other. So the most likely dates for Fed rate cuts would be June 10 and July 29. There is a FOMC meeting on September 16, but that gathering occurs less than seven weeks ahead of the November 3 election. The first post-election meeting will be held on Thursday November 5.

For now, we are sticking with our forecast that the FOMC will keep rates unchanged through 2020. But this forecast rests on the underlying assumption that the COVID-19 outbreak remains more or less manageable. But the situation is obviously very fluid, and recent events raise credible questions about the validity of this assumption. We will continue to monitor the situation closely, along with its implications for the U.S. economy and Fed policy.

1 The FOMC makes its forecasts publicly available four times per year. Its last forecast was published following the December 11 FOMC meeting. The next forecast will be made publicly available on March 18.

2 See our Monthly Economic Outlook (February 12, 2020), for further details on our outlook.