Executive Summary

With cases of the new coronavirus continuing to climb and extensive measures being taken to curtail its spread, the economic impact now looks likely to be greater than the SARS outbreak in 2003. Not only is China a bigger player in the global economy generally, but U.S. supply chains are more entwined with China today than in the early 2000s. China accounts for roughly twice the share of U.S. capital goods and industrial supply imports than it did at the time of the SARS epidemic.

The situation remains quite fluid, making it difficult to prognosticate with any precision on the impact to the U.S. factory sector. That said, the toll on U.S. manufacturing production is likely to be borne most heavily in the computer & electronics industry given its reliance on Chinese-made inputs as well as its relatively high share of industrial production. Few other industries, however, bear both high input exposure to China and command a large fraction of U.S. production. High levels of inventories in the manufacturing sector also suggest spillovers to U.S. production could be limited, at least for a time. That said, the likely drawdown in inventories along with the production halt of the 737 MAX suggests inventories could again be a sizeable drag on U.S. GDP in Q1-2020.

An Increasing Human and Economic Toll

Upon the initial onset of a new coronavirus out of China, the SARS outbreak of 2003 served as good starting point for the potential economic impact of the virus. The virus and possible economic impact, however, is quickly growing in scope. The number of cases for the new virus, officially deemed 2019-nCoV, is now more than double the cases of SARS (+20,000 versus 8,100). But beyond the human toll, a number of factors make the current outbreak likely to be more damaging to the U.S. economy.

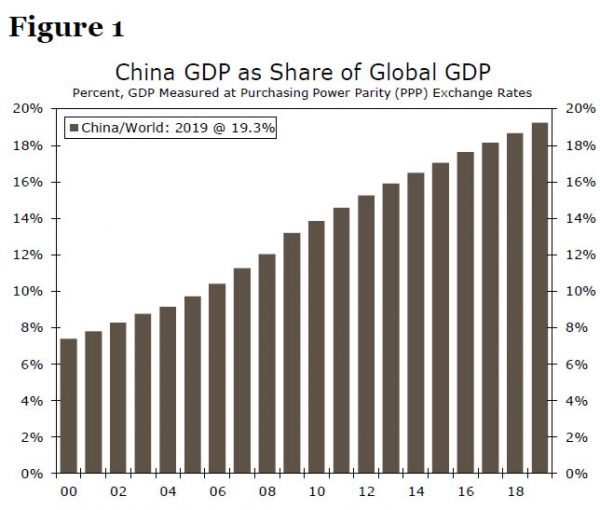

For one, China is more integral to the global economy than it was in 2003, accounting for 19% of global output compared to 9% in 2003 (Figure 1). As a result, the measures being taken to stem the spread of the virus stand to have a greater bearing on spending as well as production, which we focus on in this report.

Production in China is already being hampered by the government’s requirement to extend Lunar New Year closures by a week. Meanwhile, travel is being limited in and out of Hubei province, the epicenter of the outbreak with a population of around 60 million, while other regions are encouraging travel be postponed. Each year there is some disruption to staffing following the Lunar New Year holiday, but the travel restrictions and fears of the virus more generally could keep more workers than usual from returning to their jobs, gumming up production for even the factories that have reopened.

Chinese Supply Disruptions: Which U.S. Industries Are Most at Risk?

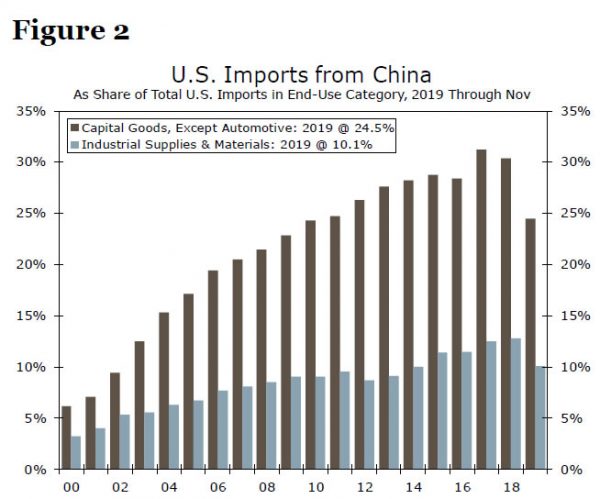

The situation remains very fluid at this point, but given the extent of the virus and the measures being taken to curtail its spread, the risk that U.S. production will be affected is quickly growing. Not only does China account for a greater share of the global economy, but it has become a bigger part of the U.S. supply chain. At the time of the SARS outbreak, only 12.5% of U.S. capital goods imports came from China (Figure 2). That share has more than doubled, however, even after the trade war curtailed capex imports from China over the past year and half. The share of industrial supplies imported from China has similarly doubled since the early 2000s.

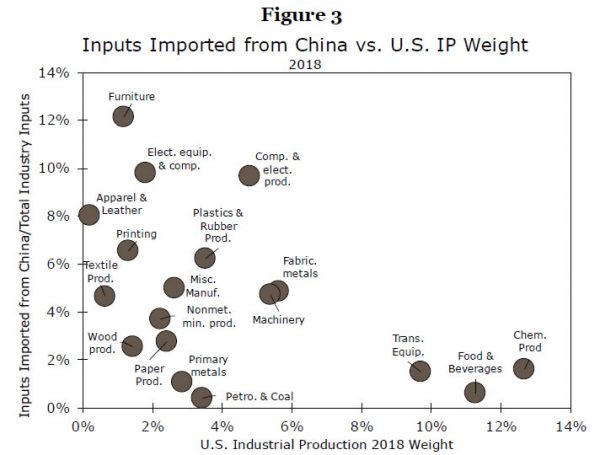

Not all U.S. industries are equally exposed to the supply chain disruptions stemming from the virus. As shown in Figure 3, the computer & electronic products industry stands to be the most directly exposed, with about 10% of the industry’s inputs imported from China.1 Computer & electronic products manufacturing accounts for 4.8% of total U.S. industrial production (IP)—making it only slightly smaller than the motor vehicles sector where output was recently roiled by the GM strike and bigger than the aerospace sector that is pending a significant hit from Boeing stopping production of its 737 MAX model at the start of the year.2 In other words, if the computer & electronics industry’s supply chain gets disrupted by the coronavirus, it could have a noticeable impact on total U.S. output. Less exposed but still posing a significant risk are the electrical equipment & components and the machinery industries, with a decent reliance on Chinese inputs (10% and 5%, respectively) and representing a chunk of U.S. IP (1.8% and 5.4%, respectively).

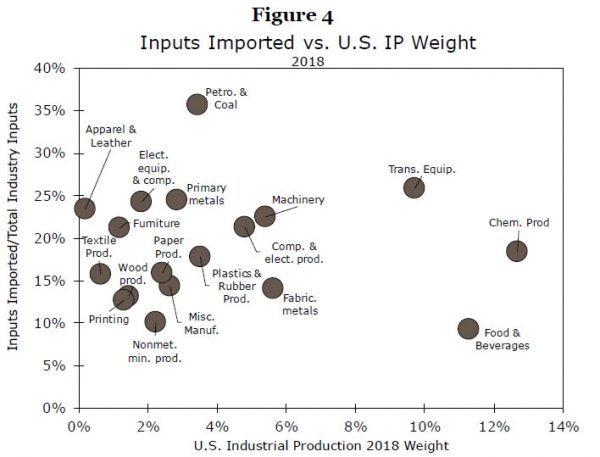

But, as we said, not all industries are equally exposed—take chemical products for example. Chemicals represent a whopping 12.7% of U.S. output—the largest share of any manufacturing component—but only a fraction of inputs come from China (1.6%). The low reliance on Chinese inputs should shelter chemical production from disruption, but only to a degree. With the virus still spreading and extended production stops and transport disruptions in China, global supply chains are also at risk. While only a small share of the chemical industry’s inputs come from China, it imports nearly 20% of its overall inputs. When looking at the potential cascade of disruptions across the global supply chain and not just the direct trade linkages between the U.S. and China, U.S. production of chemicals and transportation equipment are additional areas at risk of major supply disruptions (Figure 4).

It is worth noting, however, that there are few industries that bear both high exposure to imported inputs and are a large share of industrial production. Particularly when it comes to the direct exposure to China, manufacturing industries tend to have either a high reliance on foreign inputs but low share of production (e.g., apparel & leather), or a high share of IP but low reliance on Chinese inputs (e.g., food & beverages)—or low shares of both. Second-round effects such as reduced demand out of China or other global trading partners will also weigh on U.S. production, but few industries look to have major direct exposure, limiting spillovers to the U.S. manufacturing sector.

Are U.S. Factories Ready for Prolonged Disruptions?

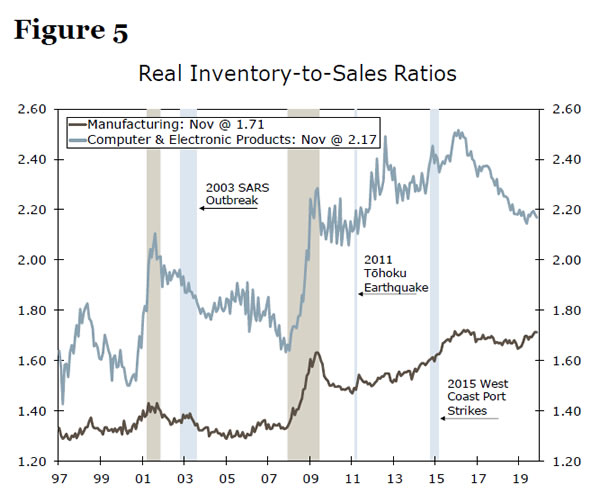

One thing that may further insulate U.S. production from wide-scale supply disruptions, at least for a time: inventories. Inventories in the manufacturing sector stand at notably higher levels than prior periods when U.S. supply chains experienced shocks (Figure 5). After years of pushing toward “just in time inventories,” supply chain managers appear to have built in some additional cushion after events like the SARS outbreak of 2003, the Tōhoku earthquake in 2011 and the West Coast Port Strikes of 2015 showed the downside of keeping inventories so lean. Low interest rates, which reduce the cost of carrying inventories, likely have not hurt either.

The greater inventory positions of the manufacturing sector extends across nearly all subindustries. The one notable exception, however, would be in computers & electronic products (Figure 5). The real manufacturing inventory-to-sales ratio in this sector is near an eight-year low, which further underscores the vulnerability of this sector to production disruptions in the near term.

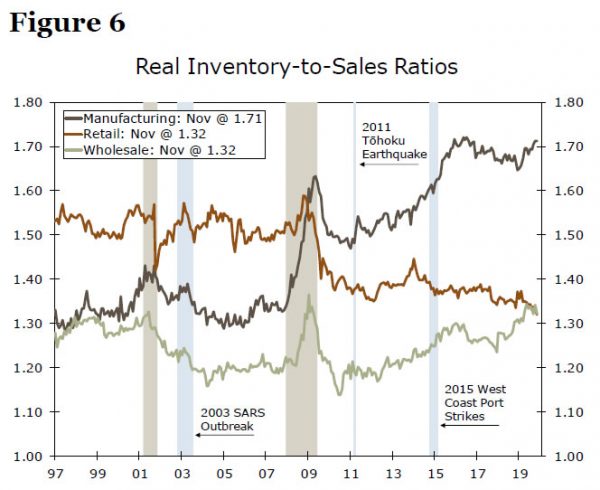

Beyond manufacturing, wholesalers also look to be at a similarly strong starting point to weather the potential supply chain disruptions emanating from the coronavirus (Figure 6). Retailers, on the other hand, appear to be at greater risk of being caught up by any production and shipment delays from China. Retailers are holding the tightest level of inventories compared to sales on record. With the exception of motor vehicle and parts dealers—an industry with little direct exposure to Chinese suppliers—inventory-to-sales ratios among all major retail categories are currently below the levels that existed around the time of the West Coast port strikes. If Chinese production and shipments are disrupted for an extended period that could eventually dampen retail sales and consumer spending in the months to come. Consumer confidence has already been rattled, although the experience of SARS and other moments of high uncertainty teach us that these disruptions have not historically kept consumer spending down for long.3

Regardless of the starting point, any supply chain disruptions stand to whittle down inventories in the coming months. That comes on top of what is already expected to be a period where inventories are hit by Boeing’s production halt of its 737 MAX. As a result of this one-two punch, inventories could be another substantial drag on GDP growth in the current quarter. If the supply disruptions from the coronavirus prove short-lived, however, the reversal of their effects along with the absorption of Boeing’s production stoppage could quickly take inventories from zero to hero when it comes to headline GDP growth. Production could similarly snap back, creating a choppy outlook for growth in the coming quarters.

Bottom Line

While the 2003 SARS epidemic initially provided a reasonable base of comparison for the current outbreak, the sheer volume of cases in the current epidemic and China’s increased role on the global stage suggest the disruptions could be larger this time. U.S. manufacturing production is likely to see at least some disruption with the computer & electronics industry being the most exposed. High levels of manufacturing inventories provide some buffers for production in the near term as businesses are able to draw down inventories without disrupting output, at least for a time. This could add to inventory variability in the first half of the year, which was already expected to be choppy due to the shifting production schedule at Boeing. Production in the United States could be adversely affected later this year if U.S. manufacturers are unable to source inputs from China for an extended period of time.

But until the full scope of this current outbreak becomes clear, exact numbers in terms of our forecast adjustment would imply a degree of accuracy we could not possibly have as the situation continues to unfold. If a vaccine become quickly available and widely distributed not only would it serve the most important function of limiting human suffering, it would also imply that the disruption to the economy is temporary and full year GDP growth would not be materially impacted. The longer it takes to resolve, the greater the potential for longer term economic fallout.

1 In order to quantify the industries most exposed we turn to the input-output tables of the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis to determine what share of each industry’s inputs is derived from imports. We estimate the share of an industry’s inputs coming from China by determining the share of industry imports that come from China and multiply that by the share of an industry’s inputs that are imported. We utilize the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) for this analysis.

2 See “Boeing Production Halt Is an About Face for Q1 Growth,” (December 17, 2019) for more detail.

3 See “Lessons for U.S. Consumer Spending from the SARS Outlook,” (January 27, 2020) for more detail.