Key takeaways

- UK formally left the EU on Friday, marking the beginning of the transition period running until 31 December 2020.

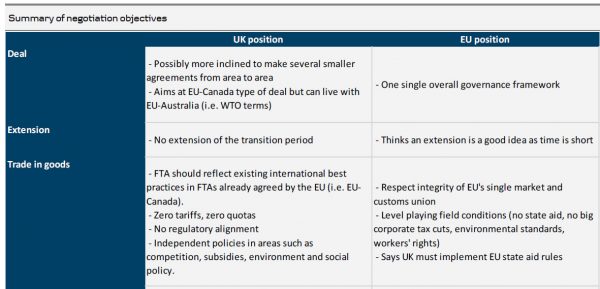

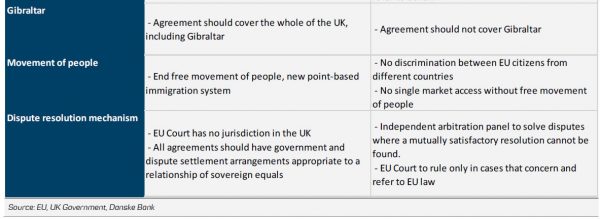

- Both the UK and the EU have published their trade agreement objectives. The most important red lines for the UK are to end regulatory alignment and the jurisdiction of the EU court. For the EU, it is to protect the integrity of the single market and the customs union, securing rights to fish in British waters and ensure the UK does not undercut EU standards (i.e. level playing field conditions).

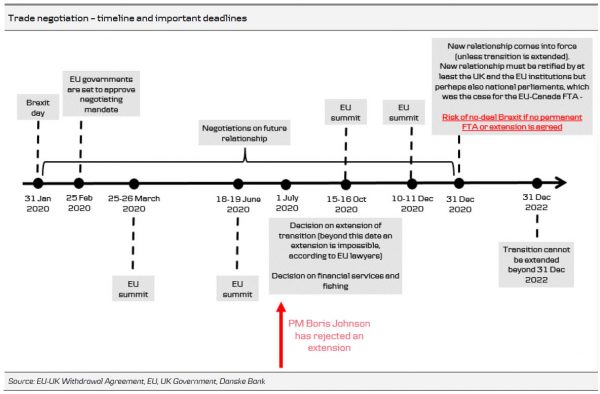

- These are initial positions and eventually both sides are likely to compromise. However, this is unlikely to happen until we are much closer to the deadline on 31 December 2020, as PM Boris Johnson has ruled out an extension.

- We think more GBP weakness is in the cards this year, as we expect investors will become increasingly impatient with the lack of progress. We also expect a 25bp cut by the Bank of England in May, as elevated Brexit uncertainty continues to weigh on business investments (see page 2).

Complicated trade negotiations ahead

On Friday, the UK formally left the EU and started the transition period running until 31 December. Both the UK government and the EU have now outlined their objectives for the forthcoming trade negotiations, which can start as soon as the EU leaders accept the objectives, set for a ministerial meeting on 25 February. Both parties have stated that the ambition is to strike a comprehensive free trade deal but it is also clear that the two parties have different priorities. For a comparison, please see the table on page 3.

As Prime Minister Boris Johnson has refused to extend the transition period, there is less than 11 months to finalise the negotiations. This is a very short time frame and the EU has already hinted it cannot be done and that the UK and the EU must prioritise the most urgent issues (see Reuters). For the EU, that means fishery and level playing field conditions (i.e. that the UK does not give British companies an unfair advantage by significantly cutting taxes, give state aid to them or slash environmental standards or workers’ rights).

PM Boris Johnson has stated that he would rather walk away from the negotiations and trade on WTO terms from 1 January 2021 than sign a deal where the UK becomes a ruletaker and falls under the jurisdiction of the EU Court, see The Guardian.

We note that EU officials have stated very clearly that the deadline of 1 July for extending the transition is an inflexible one, i.e. the EU leaders cannot easily extend the current transitory arrangements after 1 July. However, we believe that a de facto/artificial extension could be achieved by agreeing that the divergence would happen slowly over time, as part of a more comprehensive deal.

Another matter to resolve is whether the final UK-EU agreement should be ratified by only the EU institutions or the member states as well. If the deal must be ratified by all member states it complicates things, as evidenced by the experience with the EU-Canada trade agreement (for some time, a regional parliament in Belgium blocked the ratification process due to domestic political discussions). For example, an association agreement would likely be considered a so-called mixed agreement, which would have to be ratified by both the EU system and member states. An anonymous EU senior official hinted yesterday that the EU is confident the agreement will fall under EU competence, i.e. EU approval only, see The Independent.

According to the Withdrawal Agreement, the parties must agree on three things before 1 July: 1) Extension, or not, of the transition period, 2) fishery conditions and 3) financial services terms. The final deal would have to be concluded probably no later than early October in order to give enough time for ratification both within the EU and the UK. On page 4 we provide an overview of the timeline for 2020.

Our base case remains that the two parties will agree on a simple free trade agreement this year, perhaps including some elements of a de facto transition in some areas due to the short time frame. That said, the risk of a no deal Brexit from an economic perspective (i.e. trading on WTO terms) is not negligible if the two parties cannot agree on a permanent trade agreement and the transition period is not extended before 1 July. We estimate the risk at around 20%. There is also a higher risk of a no deal Brexit happening by accident, in particular if the agreement must be ratified by all member states and not just by the EU. We would not be surprised if the upcoming negotiations follow the same pattern as the withdrawal negotiations, where a compromise is not reached until we are much closer to the deadline. This is quite normal in political negotiations.

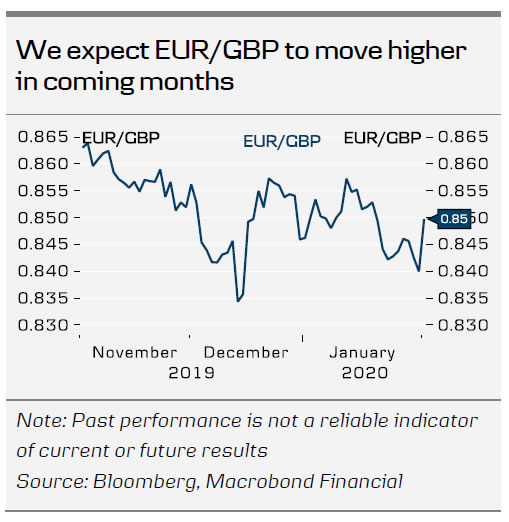

FX: More GBP is in the cards

Yesterday, EUR/GBP rose around one figure to above 0.85, from 0.84 early morning, that we think was probably driven by the initial negotiating positions outlined by the UK government and the EU. Investors appear to have become slightly more concerned about the prospects of a deal, as the initial positions seem to contradict each other.

We see two reasons for a weaker GBP. Firstly, at some point, we expect investors will become impatient about the lack of progress in the negotiations, leading to higher no deal Brexit fears. Secondly, the continued elevated Brexit uncertainty means we are unlikely to see any investment boom yet, as companies are likely to wait for the outcome of the negotiations before taking projects out of the drawer again. Weak growth would force the Bank of England to cut at the May meeting, which is not fully priced yet (60%).

We target 0.87 in 3M and 0.89 in 6M-9M, when we think the Brexit uncertainties will peak. As our base case is for the two parties to agree on a permanent deal, we think the GBP will rally as soon as such a deal is in sight. We target 0.84 in 12M.