Executive Summary

In part I of our series on the 2020 election and the U.S. economy, we examined some of the key facts about the election as it currently stands. In part II, we tackled where the candidates stand on some of the major economic policy issues. In this report, the final in our series, we delve into the actual process by which some of these proposals could become law. We examine three policymaking avenues: regular order legislation, budget reconciliation and executive orders/regulatory policy. Each of these policymaking tools comes with its own pros and cons. Regular order legislation is the most powerful tool for rewriting or creating new laws, but it often comes with the highest political hurdles given that this type of legislation can be filibustered in the Senate. Budget reconciliation is a privileged form of legislation that helps policymakers avoid the filibuster, but its special status comes with a series of rules that can make it unwieldy for some types of sweeping policy change. Actions taken by the executive branch, such as executive orders or the appointing of individuals to head key regulatory agencies, often require the least cooperation from Congress, but their power to impact the law is also often more limited, and action taken by one administration can often be reversed by its successor.

Regular Order Legislation: The Simplest Approach

It can be easy to forget that the most straightforward way to change the law at the federal level is simply for Congress to pass a bill through regular order and then have the president sign it into law. One or both chambers of Congress begin by writing and debating legislation in the relevant committees, and over time this legislation can eventually move to the full chambers. From there, one chamber can pass the legislation and then send it to the other, or both chambers can pass their own bills, and then meet in a conference committee to hash out the differences. Regardless, in order for a bill to become a law, the bill must pass both the House and Senate, each with a simple majority, after which it is sent to the president, who can either sign it into law or veto it.

When done this way, many of the challenges associated with budget reconciliation or executive orders dissipate. For example, while the budget impact of the bill as determined by the Congressional Budget Office may matter politically, it is much easier to blow up the deficit in regular order legislation than it is through budget reconciliation, which we will discuss in the next section. And regular order legislation can much more expansively and freely change and create laws across a whole host of policy areas, unlike reconciliation or executive orders.

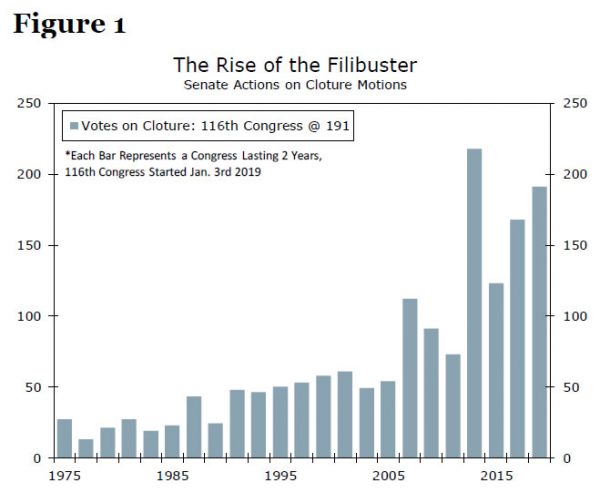

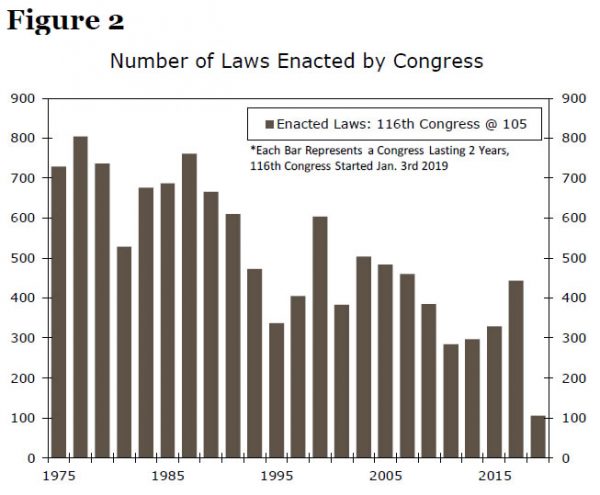

Thus, an expansive policy overhaul such as Medicare for All would be best suited to regular order legislation. The challenge is that regular order legislation can, in most circumstances, be filibustered in the Senate. More specifically, it takes 60 U.S. senators to invoke cloture, or end a filibuster (Figure 1). This means that, in practice, a determined minority of senators with at least 41 seats can hold up all sorts of legislation. In partisan times like these, the inability to clear legislation with less than 60 votes is one reason policymakers have struggled to enact new legislation (Figure 2).

In response to the increasing use of the filibuster, legislators have turned to other tools, such as budget reconciliation and executive orders, to achieve their policy priorities. That said, it is important to keep in mind that a simple majority of senators could turn to the “nuclear option” and end the filibuster, as has already been done for cabinet-level nominees as well as Supreme Court nominees. At this point in time, support for this option appears limited in both parties. Should it happen, however, it would open the door to far more wide-reaching policy reform than is likely under the status quo.

Budget Reconciliation: A Key Tool in Modern Policymaking

Budget reconciliation is a term that has grown in importance and relevance in recent years. In short, reconciliation is a fast-track procedure designed to help policymakers make changes to mandatory spending programs and tax policy. Discretionary spending, which includes components of the budget like defense spending, foreign aid and spending on most government agencies such as the Environmental Protection Agency, is determined once a year during the annual appropriations process. Mandatory spending on programs such as Medicare or Medicaid, however, is set by predetermined eligibility requirements, such as age or income. In addition, most aspects of the tax code remain the same from year to year. As a result, mandatory spending and the tax code operate a bit more on autopilot than the discretionary spending side. Reconciliation offers Congress a tool with which it can alter these parts of the budget by reconciling current law with the priorities established in the annual budget resolution.

Reconciliation has gained prominence in these partisan times due to its privileged status; final passage requires a simple majority, and debate time in the Senate is limited, preventing a filibuster by the minority party. Passing legislation through reconciliation is often a much easier hurdle to clear than the de facto 60-vote threshold needed to end a filibuster when considering legislation in the more traditional way. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act passed at the end of 2017 was done using reconciliation, as were the Bush tax cuts in the early 2000s. A portion of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was also enacted through reconciliation, and the failed Republican ACA repeal effort in 2017 attempted to use the reconciliation process too.

Because of its special rules, the contents of a reconciliation bill are tightly controlled.1 Several of these restrictions fall under the “Byrd Rule,” which governs what is and is not allowed under reconciliation. A provision of a reconciliation bill violates the Byrd Rule if any of the following apply:

- It does not produce a change in outlays or revenue.

- The net budgetary effect of a title reported by the reconciled committee is such that the committee does not achieve its fiscal target (“title” here loosely meaning a broad section of the bill).

- The committee reports a title containing matter outside its jurisdiction.

- The budgetary effects of a provision are “merely incidental” to the overall policy objective.

- The reported title causes an increase in the deficit in any year outside the budget window2.

- The provision makes changes to the retirement and disability programs in Title II of the Social Security Act.

Broadly speaking, these restrictions are designed to help ensure that Congress utilizes reconciliation for its original budget-related purpose and not simply to take advantage of the special rules governing this type of legislation. In many cases, the two most difficult Byrd Rule hurdles to overcome are the rule against increasing the budget deficit outside the 10-year budget window and the rule against policies whose objectives are “merely incidental” to the budget. In the first case, this is why the Bush tax cuts and some of the TCJA were made temporary rather than permanent. By making some of the TCJA expire in 2025, this helps ensure that the deficit only grows within the first decade of enactment. The “merely incidental” clause is a bit fuzzier, but essentially it boils down to a judgement call on whether the policy under consideration is truly a budgetary one. One can always make a ‘butterfly effect’ argument that a change in policy will have some budgetary impact; it is up to the Senate parliamentarian to determine whether this budgetary impact is “merely incidental” to the overall policy objective. Cutting taxes, for example, has a very clear policy objective linked to the federal budget, but banning the use of fossil fuels requires a bit more of a stretch when claiming that the policy objective is a budgetary one.

How might reconciliation lend itself to some of the major progressive policy proposals from the 2020 Democratic candidates, such as Medicare for All or student loan forgiveness? This early on, it is impossible to say for sure what would and would not be a problem, but for illustrative purposes we highlight a couple examples. On the Medicare for All side, using reconciliation could be difficult. For example, it might be hard to make the case that abolishing all private insurance is a policy whose objective is primarily budgetary in nature (i.e. the budgetary impact is not “merely incidental”). Another challenge for Medicare for All would be fully paying for it such that it does not add to the deficit outside the 10-year budget window. Medicare for All could have an expiration date like parts of the TCJA, but overhauling the entire healthcare sector and giving those changes an expiration date would create tremendous uncertainty. Offsetting tax hikes could solve this problem, but the tax hikes necessary to prevent a Byrd Rule violation could prove politically unpalatable, particularly if the Joint Committee on Taxation scores them in a way that shows significant damage to the U.S. economy.

Recognizing these challenges, Elizabeth Warren has proposed doing Medicare for All in two stages. First, Democrats in Congress would utilize reconciliation to make Medicare itself more generous, such as lowering the eligibility age to 50 and creating an opt-in option for everyone else. Then, Warren has said that by the second half of her second term, she would fight to pass legislation that would complete the transition to full Medicare for All, with the hope that Americans would at that point see the full benefits of such a plan and embrace it.

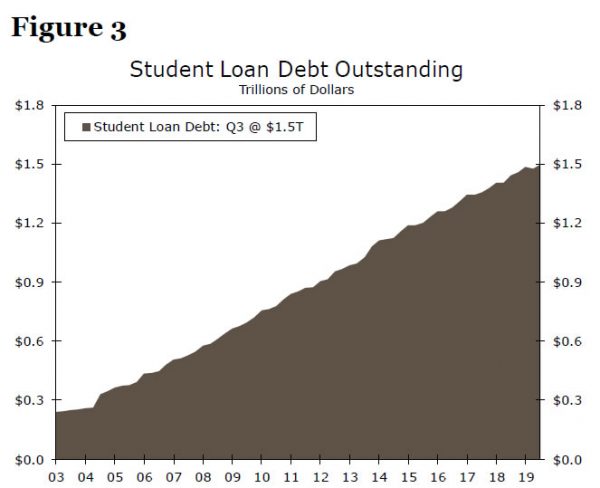

Forgiving student loan debt, on the other hand, would likely be more conducive to reconciliation than Medicare for All. It has a very clear budgetary impact, but it would still need an offset to avoid the long term deficit increasing portion of the Byrd Rule. The numbers behind student loan debt forgiveness are more manageable; total student loan debt outstanding is about $1.5 trillion, compared to some leading estimates of Medicare for All, which peg the cost at $34 trillion over 10 years (Figure 3). Our point in these two examples is not to say that Medicare for All has no chance at passing through reconciliation, or that student loan debt forgiveness would fly through problem-free. Rather, we use these two policy areas to illustrate some of the opportunities and challenges policymakers might face should they strive to use this tool after the 2020 election.

Executive Power: Easiest to Change…and Change Back

Most Americans are taught at a young age that the three branches of the U.S. government look something like this: Congress writes the laws, the president enforces them and the courts decide cases over those laws. Thus, at the most basic level, it is important to bear in mind that presidential authority is derived from either power vested in the president by the U.S. Constitution or power delegated to the president by Congress.3 The enforcement of the law requires a significant amount of rulemaking and policing, jobs typically carried out by the various federal government agencies that are part of the executive branch.

The main benefit of executive action from the standpoint of the president is that it often does not require Congress to pass anything. Trade policy, for example, is an area where Congress has delegated quite a bit of authority to the president. The tariffs that President Trump placed on Chinese imports and other U.S. trading partners have been done without votes in Congress, and as such this avenue is a much more straightforward way for President Trump to achieve his policy goals. But, this is not to say the president’s powers on this front are unlimited. Since this authority is derived from previous laws passed by Congress, it is also Congress’ prerogative to take some of this power back, should it so choose. Furthermore, a future president often has the power to reverse many executive actions taken by previous presidents. For example, a successor to President Trump could relatively easily remove many of the tariffs that have been put in place over his term. And when it comes to appointing people to important posts, such as the Chair of the Federal Reserve or the head of the Department of Energy, many of these high level officials must be confirmed by the Senate, giving Congress some sway over who is running the key institutions in the executive branch.

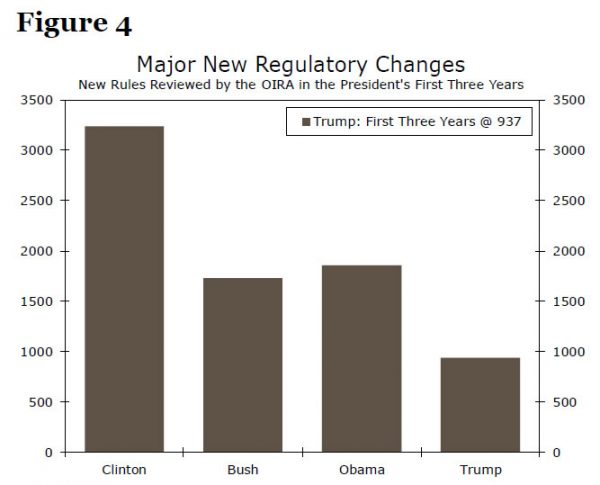

In addition, the president’s powers are limited in that the executive cannot create or wholesale modify laws in the way Congress can. What the president can do is utilize latent powers delegated to the executive branch, or select important political appointees that will change how the law is enforced. Under President Trump, for example, the pace of new major regulations has slowed compared to his predecessors (Figure 4). At a more micro level, take prescription drug prices as a sample policy issue. Bringing down the cost of prescription drugs has been a policy priority of both parties of late, and both Democrats in the House and Republicans in the Senate have released legislation to try to tackle this issue. So far, the two sides have not been able to pass sweeping reform, and the Trump Administration has attempted to step into the void and do what it can to bring down drug costs. In December 2019, the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) announced that the administration is open to allowing some prescription drugs to be imported from Canada as a means of lowering prices. How did the administration get around the import restrictions put in place by Congress in 1987? As part of the 2003 law that established the Medicare Part D drug benefit for seniors, Congress allowed some select medicines to be imported from Canada if HHS certified them as safe and cost-saving. But no HHS secretary had taken on that task until recently. Thus, the current administration is reaching into an old law for the authority it needs to make a policy change. But, its ability to go above and beyond the authority granted in this law is limited, unless it can find additional authority elsewhere.

Another example would be the ongoing effort by financial regulators to reconsider how the Volcker Rule is enforced. Since the Volcker Rule was written into law by Congress in the Dodd-Frank bill, it cannot be wholesale eliminated by the regulators even if they wanted. But, what does and does not count as proprietary trading requires quite a bit of complex rulemaking, and this is where there is some latitude for a president to nominate individuals to important posts who will use their roles to implement some incremental policy changes.

Conclusion

In presidential election cycles, candidates generally offer a wide range of expansive policy proposals. The path by which these proposals become law, however, is often much less clear. Amid increasing polarization, the traditional means by which Congress enacts legislation has become more challenging, pushing legislators to use alternative methods. Budget reconciliation and executive action can be effective means of implementing policymakers’ agendas, but they have their constraints. Generally speaking, the bigger change that a president or legislator is trying to affect, the more difficult it is to achieve through the alternative approaches to traditional legislation.

1 For those interested in a longer primer on reconciliation and the Byrd Rule, see Heniff Jr., B. (2016). “The Budget Reconciliation Process: The Senate’s “Byrd Rule“.” Congressional Research Service.

2 At present, the budget window covers the current fiscal year and the subsequent 10 fiscal years, although this has not always been the case, as some budget windows were previously just five years.

Chu, V.S. & Garvey, T. (2014). “Executive Orders: Issuance, Modification, and Revocation.” Congressional Research Service.