Executive Summary

- Although the Eurozone economy has picked up in recent weeks, there are still signs that growth remains weak. In our view, the economy needs to show more concrete signs of stabilization before we call the “all clear” on recession risks.

- Given the overall softness in the Eurozone economy, we expect the European Central Bank (ECB) to cut rates an additional 10 bps to -0.60% at its December policy meeting.

Eurozone Economy Walking the Tightrope

Market sentiment toward the Eurozone economy has slowly started to turn more positive, or less negative, in recent weeks. Eurozone GDP rose 0.2% quarter-over-quarter in Q3, more than expected, and Germany unexpectedly avoided a technical recession, while industrial output posted a surprise gain in September. However, this morning’s PMI data for November are a reminder that the Eurozone economy remains extremely weak. The composite PMI fell to 50.3 amid a drop in the services PMI to 51.5, although the manufacturing PMI edged up to 46.6. These data suggest Q4 GDP growth will be quite weak in the Eurozone, perhaps just barely positive. The key issue in our view is still the interplay between manufacturing weakness and resilience in the services sector.

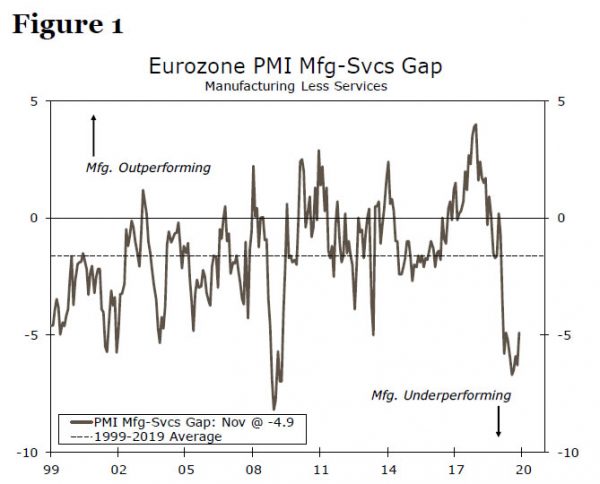

It is hardly a secret that the manufacturing sector has been the primary source of the Eurozone’s woes, just as we have seen in other major developed economies. The scale of the divergence between services and manufacturing has been stark, as the manufacturing PMI fell more than six points below the services PMI in October, although that gap narrowed a bit in November (Figure 1). We doubt divergence on this scale will last much longer—either the manufacturing sector must recover or the services sector and economy more broadly risks being dragged into recession.

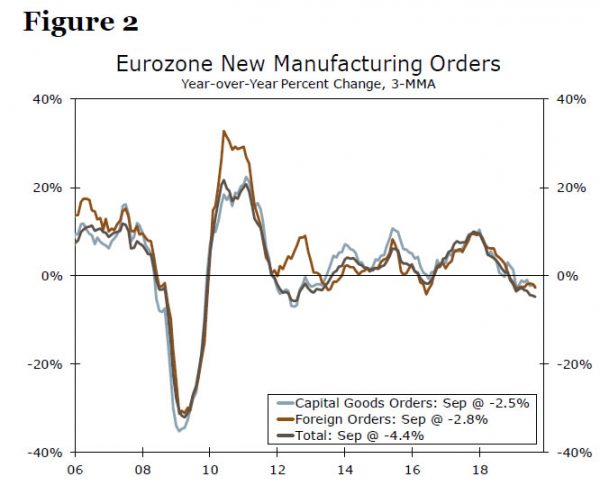

Fortunately, there are some tentative signs that the manufacturing sector is stabilizing, and for now we expect a manufacturing recovery rather than a services sector collapse. For one, we have seen an uptick in manufacturing PMI readings for both the Eurozone and Germany, the latter of which has been the primary source of malaise of late. We are also encouraged by recent data on new orders for manufactured goods, a leading indicator of production. While the latest data show that manufacturing orders in aggregate may not have bottomed yet, there are more encouraging signs beneath the surface. First, orders for capital goods, which tend to be the most forward-looking indicator of demand within total orders, have shown more stability in recent months than total orders (Figure 2 on previous page). Moreover, slicing the data a different way, foreign demand for Eurozone manufactures has also steadied in recent months, a sign that stabilization in global growth more broadly may be starting to feed through to the Eurozone economy.

Meanwhile, hard data in the services sector continue to show signs of resilience. Wage growth remains fairly solid and above 2% year-over-year based on most measures, while core inflation has essentially been stuck at 1% year-over-year for the past few years, implying sturdy real income gains. To be sure, employment gains have slowed meaningfully, but the jobless rate has continued on a downward trend throughout the year. Amid this constructive consumer backdrop, retail sales have actually accelerated in recent months despite ongoing weakness in other parts of the economy. However, our concern is that, while the Eurozone economy is showing signs of bottoming and seems likely to avoid recession, it is also unlikely to stage a quick recovery in our view. Instead, we think Eurozone economic growth will remain sluggish for the foreseeable future.

Surviving, but Not Thriving

Our outlook for continued softness in the Eurozone economy reflects a few factors. First, the domestic policy environment has eased over the course of the year, but likely not enough to have a significant positive impact on domestic demand. To be sure, market interest rates and bank lending rates have moved lower in 2019. However, the composite cost of borrowing for non-financial corporations has fallen just 10 bps over the past year, roughly in line with the drop in three-month EURIBOR. That is a welcome safety net for an economy that has slowed as much as the Eurozone has, but is fairly modest considering the extensive package of easing measures that the ECB announced in September, and probably not as substantial as the central bank had hoped.

Meanwhile, despite the substantial amount of fiscal policy space available for low-debt economies in the Eurozone, particularly Germany, the willingness to provide substantial fiscal stimulus remains low. To be sure, Germany appears to be on track to run a slightly smaller budget surplus in 2019 relative to 2018, a modest easing of fiscal policy. However, that may simply reflect cyclical factors such as higher spending on automatic stabilizers, including unemployment insurance, and lower tax revenues amid slower economic growth. Even within the current German constitutional rules limiting the extent to which the government can ease fiscal policy (maximum structural budget deficit of 0.5% of GDP for the general government), policymakers have some room to maneuver, but do not seem to be taking advantage of that policy space. In our view, the fact that the government has been so hesitant is both telling and concerning, and we think it might take an outright recession with a meaningful rise in unemployment for Germany’s government to sanction any sort of large-scale fiscal stimulus.

With fiscal policy support largely absent, and past easing measures from the ECB having had a limited positive impact on monetary and financial conditions, we anticipate that the ECB will ease policy further in December. Specifically, we think the central bank will cut its deposit rate by an additional 10 bps to -0.60%. However, we acknowledge that markets are currently pricing essentially no easing in December. The December policy meeting could be a wild card given it is newly appointed ECB President Christine Lagarde’s first meeting. However, ECB Chief Economist Philip Lane has recently said that the central bank is not yet at the lower bound, and Lagarde’s comments on policy thus far suggest that she will likely support additional policy easing.

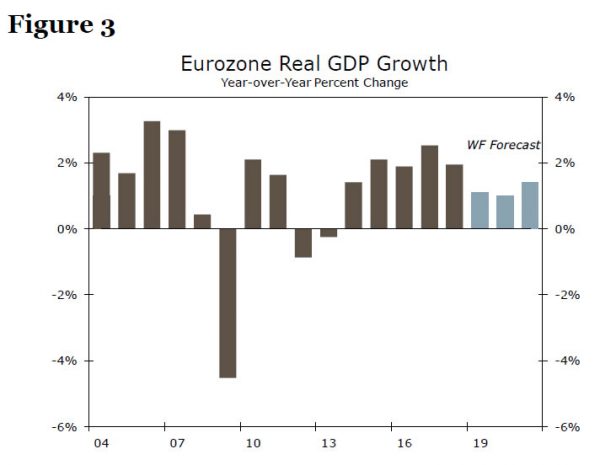

Beyond December, we think the ECB will refrain from further rate cuts. This reflects our view that stabilizing global growth, particularly in the United States, will bail out the Eurozone economy. Our forecast calls for U.S. GDP growth to bottom out in the coming quarters before picking up as 2020 progresses. We also expect the U.K. Conservative Party to win the December general election and ratify a Brexit deal in early 2020, which would probably be a modest positive for the Eurozone economy. However, we reiterate that the Eurozone is likely to have a U-shaped, not a V-shaped recovery. As mentioned above, that partly reflects the weakness of the Eurozone policy impulse. Another key ingredient missing from the recipe for a stronger Eurozone rebound is China. The Chinese economy has continued to slow over the course of the year, and we expect it will soften further into 2020 and beyond—albeit gradually—as authorities refrain from significant “big-bang” monetary and fiscal policy easing. An ongoing slowdown in China’s economy will likely limit the extent and speed of any Eurozone recovery. On balance, we forecast Eurozone GDP growth of just 1.1% in 2019 and 1.0% in 2020 (Figure 3).