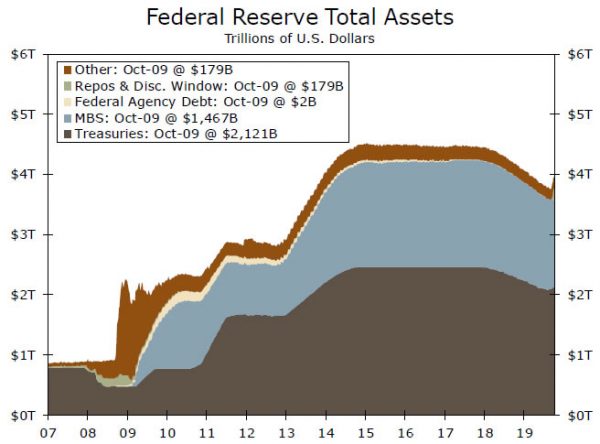

For the first time since 2013, the Federal Reserve is set to grow its balance sheet again. Although the mechanics look similar to QE, the motivations behind these asset purchases are much different than previous programs.

Fed Bond Buying Coming, but Don’t Call It QE

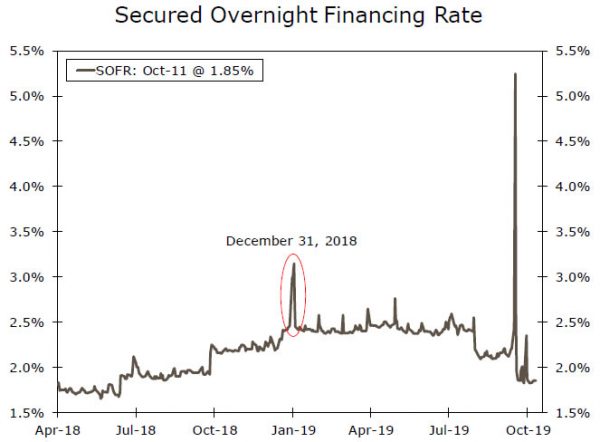

On October 4, the FOMC clandestinely met via video conference to discuss possible solutions to recent repo market volatility, a topic we covered extensively in a recent report. Then, on October 11, the committee announced the following policy actions that resulted from that meeting.

In its statement, the FOMC committed to, at least through January 2020, “conduct overnight and term repo operations to ensure that the supply of reserves remains ample.” The Fed has been conducting overnight and term repo operations since repo rates skyrocketed on September 16/17, so this policy is simply an affirmation that the Fed will not be stepping away from the market anytime soon. This was mostly in-line with our expectations: even with an asset purchase program in place, it would take a few months before the impact of more reserves/fewer Treasury securities will be fully felt.

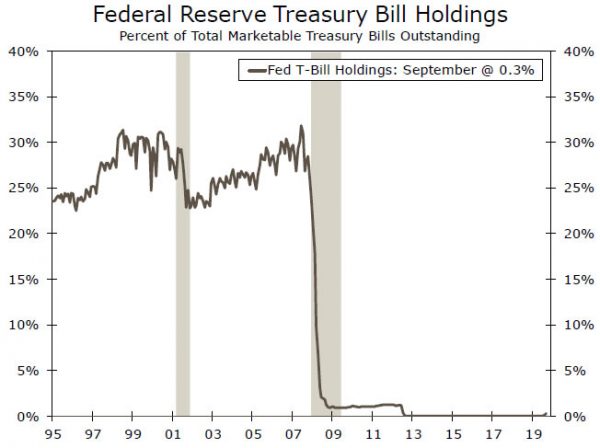

Second, the FOMC announced that the Fed will “purchase T-bills at an initial pace of approximately $60 billion per month, starting with the period from mid-October to mid-November.” There was no explicit number on additional purchases past that, but there was a commitment to “purchase T-bills at least into the second quarter of next year to maintain over time ample reserve balances at or above the level that prevailed in early September 2019.”

Purchases of $60 billion/month for six months would exceed the estimates we proposed in our Sept. 27 report (roughly $250 billion in total). When viewed through this lens, the Fed’s actions seem more aggressive than expected. Purchases at this pace would result in the Fed going from owning a tiny share of the T-bill market to 15% in just six months (middle chart).

That said, the FOMC has left itself plenty of wiggle room to adjust this number going forward. Purchases of $60 billion/month for six months would put total reserves well in excess of the level that prevailed in “early September 2019”. Our best guess is that the plan is to act boldly between now and yearend, as year-end is when funding pressure are expected to be most acute (bottom chart). Thus, we think the most likely outcome is that the Fed buys $60 billion per month through the end of the year and then scales back its purchases. For example, if the Fed were to buy $60 billion in the first two months, $45 billion in the next two months and then $30 billion in the final two months, this would put it on pace to cumulatively buy $270 billion in Treasury securities, roughly in-line with our initial projections.

Finally, Fed officials have repeatedly emphasized that these purchases are not QE, as the main motivation is to add banking reserves to the system, and not to put downward pressure on long-term interest rates, as was the case in previous asset purchase programs. These policy moves do not alter our view that the FOMC will cut the fed funds rate twice more in the months ahead.