Stock markets around the world have rebounded this week as talk of stimulus in China and Germany has given rise to hopes that pre-emptive action by policymakers can avert a global economic downturn triggered by President Trump’s protectionist policies. But with a US-China trade deal fast slipping away, do governments and central banks have enough firepower to prevent a new global crisis from unfolding?

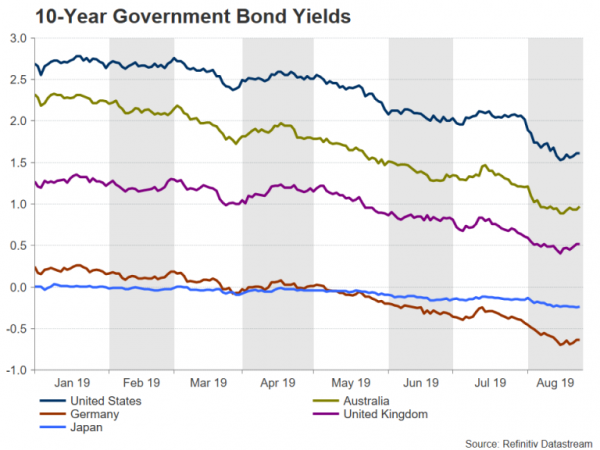

World interest rates have hit rock bottom

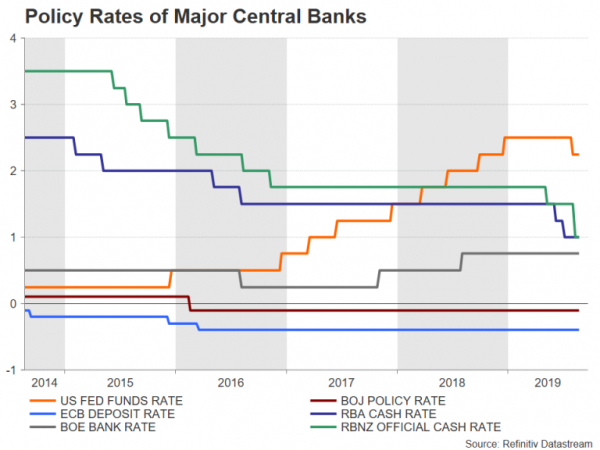

With interest rates in most advanced economies not recovering to pre-financial crisis levels almost a decade after emerging from the global recession, the undesirable situation that many central banks find themselves in has been a long time coming. Policy rates from Europe to Japan are stuck in negative territory, raising questions as to how central banks will respond to the next downturn. Other central banks such as those in Britain, Canada and Australia have a few 25-basis points (bps) cuts at their disposal, though this would hardly be enough to fight a major economic meltdown.

The US Federal Reserve is in a somewhat more enviable position as it was the only one that managed to raise rates by an impressive 225 bps so cutting them back to zero would provide a significant boost without having to resort to quantitative easing. Taking into account the United States’ stronger economic fundamentals as well, there’s even less cause to be concerned about the American economy. However, sluggish growth is unlikely to satisfy the White House when elections are just around the corner and the Trump administration is toying with the idea of new tax cuts to shore up growth ahead of the 2020 presidential race.

Recessions risk rises as trade tensions worsen

Nevertheless, a recession in the US cannot be ruled out if the trade fight with China worsens in the coming months, leading to even higher tariffs and deteriorating growth in the US’s other main trading partners. But even in such a scenario, a deep recession in the US seems unlikely and a greater worry would be the impact on more export-dependent nations such as Germany, Japan, and of course, China.

China has been actively pursuing both monetary and fiscal policies to stimulate its economy even before the trade row started and has stepped up its efforts since the first wave of US tariffs struck the country. The latest measure to come from the country involves reform to its key lending rates, with the aim of lowering borrowing costs for households and businesses. So, although China would continue to feel the direct impact of the trade war, authorities are sure to maintain their pro-active approach in softening the blow to the economy as much as possible using a variety of tools.

Government inaction a problem for the Eurozone

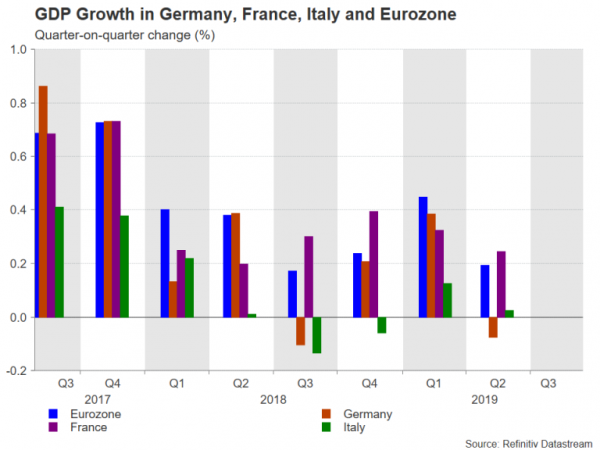

However, ‘pro-active’ is definitely not a word that can be used to describe German policymakers, who are only now coming around to the idea that Europe’s largest economy, which is on the brink of a recession, could do with a helping hand. The German government has suggested it can spend up to 50 billion euros to bolster the economy.

In the rest of the Eurozone, with the exception of Italy, the situation isn’t quite as dire as in Germany. Should the European Central Bank go ahead and announce a large stimulus package in September as expected, this could potentially cushion most member states from the brunt of the trade war. However, a prolonged and unresolved conflict risks dragging the entire euro area into a full-blown recession.

Japan running out of ammunition

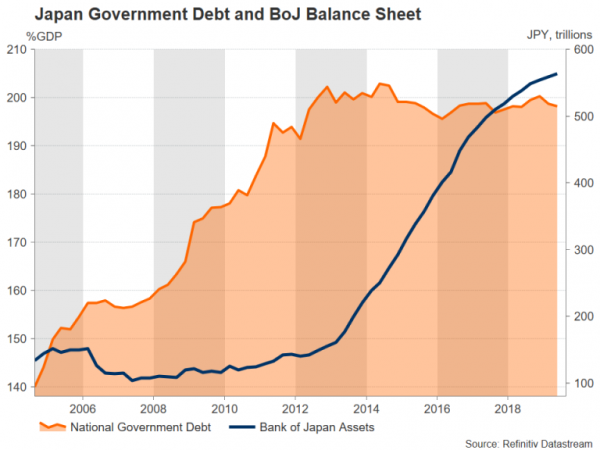

Another vulnerable country is Japan, where both the government and the Bank of Japan have limited scope to increase spending and asset purchases after years of multiple stimulus packages intended to kick-start stagnant growth and lift inflation. Aside from the never-ending trade dispute, another risk for Japan is the planned sales tax hike for October, which is expected to weigh on consumption.

A resilient domestic demand picture is what has kept growth positive in recent quarters amid declining exports. If the tax hike tips the economy into recession, the government could be forced to come up with a new fiscal package, while the BoJ would almost certainly have to ramp up its stimulus. Given the BoJ’s history of inventing unorthodox policy tools, policymakers are likely to find new ways of expanding their already ultra-loose monetary policy should Japan be hit with a downturn.

How effective this would be given the risk of diminishing returns is another matter, but perhaps a more interesting question is what would happen to the yen if the BoJ opts for another massive stimulus package. The yen is the best performing major currency in the year to date, rising sharply versus the euro, pound and the antipodean currencies, and is up about 3% against the US dollar. Should the BoJ join other central banks in loosening monetary policy, the yen is likely to lose some of its current appeal, which is underscored by its safe-haven status.

Yen and gold are ones to watch

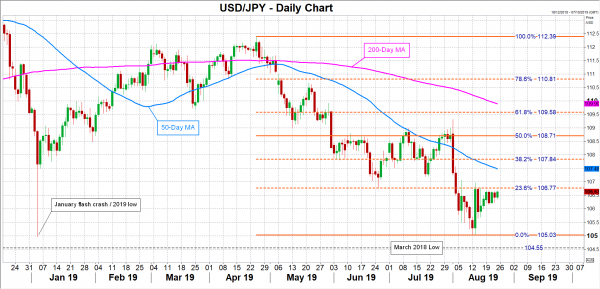

A weaker yen could push the dollar back up the 108-yen level, with a break above 109.58 – the 61.8% Fibonacci of the April-August downleg – possible if the size of the stimulus is considerable. However, if the BoJ fails to deliver anything substantial, the next key target for dollar/yen to the downside would be the 104.55 region.

Those seeking a safer bet than the yen, as central banks around the world drive government bond yields to record lows, are likely to turn to gold, which has already rallied to more than 6-year highs on a combination of escalating trade tensions and falling yields. Having broken above the $1500/ounce level earlier this month, the next big test for the precious metal in the coming months will be the $1585 area, which is the 61.8% Fibonacci retracement of the long-term downtrend from $1,920.30 to $1,045.85.

Has monetary policy run its course?

But as investors adjust their outlook to the prospect of a protracted trade war and lower borrowing costs around the world, there are doubts about how effective easier monetary policy will be this time around given the fact that many central banks such as the ECB and BoJ have exhausted most of their policy tools. Consequently, this has turned the spotlight on fiscal policy.

Many investors have long been calling on the growth laggards such as the Eurozone to ease up on stringent spending rules. But just as markets have been given hints that a fiscal boost could be on the way, there’s already some uncertainty about politicians’ commitment to increased spending and tax reductions.

Will the Germans step up?

In Germany – the country seen as most in need of a fiscal stimulus – it’s unclear whether the government’s plans being drawn up to provide a 50-billion-euro fiscal package would get approved by a debt-conscious parliament. Even if it was to get through lawmakers, there’s the prospect it would be too little too late.

Meanwhile, President Trump appeared to backtrack on earlier comments that he was seeking to cut taxes on payrolls and capital gains in the US. In contrast, some nations like Australia are way ahead of the curve with the Reserve Bank of Australia cutting interest rates twice by a total of 0.50% and the government announcing tax cuts.

Could a coordinated fiscal response be on the cards?

The global move towards looser monetary policy and encouraging signs that fiscal aid could also be forthcoming from the big economies has helped maintain some level of optimism in financial markets amidst all the gloom from the trade war as well as Brexit and other global woes. This has been most evident in stock markets where shares have jumped higher on the slightest indication of stimulus.

However, if in the coming months, the trade dispute is still nowhere near being resolved and the global growth picture deteriorates further, investors will probably start pinning their hopes on something of a much grander scale such as a coordinated response by major governments similar to that seen during the 2007-8 financial crisis, only this time, the focus would be on fiscal stimulus. With global bond yields at record lows and many in negative territory, there hasn’t been a better time for governments to go on a spending spree – the question is, will they rise to the challenge?