Highlights

- Canadian economic growth has decelerated markedly, and a repeat of the fourth quarter’s near-zero pace is expected in 2019Q1. This growth slump has led clients to question whether Canada can contract or stagnate alongside an otherwise healthy U.S. counterpart.

- It is rare, but the answer is yes. The typical escape valve of an improving external trade balance is less impactful than in the past. The present situation echoes 2015, but with slightly different drivers at work.

- The term recession is thrown around a lot without appropriate qualifiers. Absent a severe external shock, the risk we see is at most a ‘technical’ recession, with the more likely outcome a short period of stagnation. Any throttling back in activity is likely to lack the required combination of breadth, depth and duration to mark a true recession.

- Labour markets and credit growth are the key areas to watch in assessing the risk of a downturn.

Canada is in the midst of a growth slump. Weaker-than-expected near-term economic momentum has emerged, at the same time that energy sector production curtailments are sending growth temporarily lower. Today’s weak GDP report (0.4% q/q saar) is likely to be followed with another near-zero out-turn in 2019Q1. Such a modest forecast means that it would not take too much of a miss versus expectations to send first quarter growth into negative territory. This has led clients to question the possibility of Canada entering a recession independent of a downturn in the United States.

A ‘true’ recession that hits all the economic markers is highly unlikely, but a technical recession is a possibility. A ‘technical’ recession is defined as lacking the combination of depth, breadth and duration. This is where GDP may contract or stagnate for two or more quarters in the absence of a parallel broad labour market stress. This is also where the bar is set for a ‘true’ recession that comes with widespread industry output contractions and significant employment losses across much of the nation.

We need only look back to 2015 to find evidence that Canada can indeed experience a ‘technical recession’ while the U.S. continues to expand. Although this is not common historically, we believe it’s possible that Canada may experience more of these temporary de-couplings from U.S. dynamics in the future. The “escape route” for Canada has often been the external sector, where depreciation of the Canadian dollar and healthy U.S. demand help to offset weakness elsewhere in the economy. This dynamic, however, has become more muted over the years, and other growth drivers lack pent-up demand to offer a large cushion (i.e. the housing sector and consumer spending).

Within the current cycle, the risk of a technical recession cannot be dismissed, but the data does not point to a downturn at present. Indeed, an assessment of key leading indicators points to a growth slump, not a contraction.

Getting our definitions right

Discussions of recession risks can often get bogged down in definitional distinctions, so it is important to distinguish between three types of economic performances before delving into the analysis. The first is a growth slump, where the economy manages to eke out growth, but just barely. This is, in effect, our near-term forecast. The second is a ‘technical’ recession (sometimes called a ‘statutory recession’ as it meets the definition included in the (since repealed) Federal Balanced Budget Act of 2015. This requires at least two consecutive quarters of economic contraction, and little else. A ‘true’ recession has a much higher bar – not only an economic contraction, but one that comes with breadth and depth. Compare for instance, the 2008/2009 recession, which saw the national unemployment rate rise 2.5 percentage points (and rise in all provinces), with the 2015 statutory recession, where the increase was a more modest 0.5 percentage points, driven by a narrow set of provinces with exposure to the energy sector: Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Newfoundland and Labrador.

The focus of this analysis is on the risk of a technical recession, which cannot be ruled out simply because of strong U.S. economic dynamics. The risk of a ‘true’ recession is quite low at present, and has effectively never occurred in history without a matching contraction south of the border.

Weakened external channels heighten Canadian risks

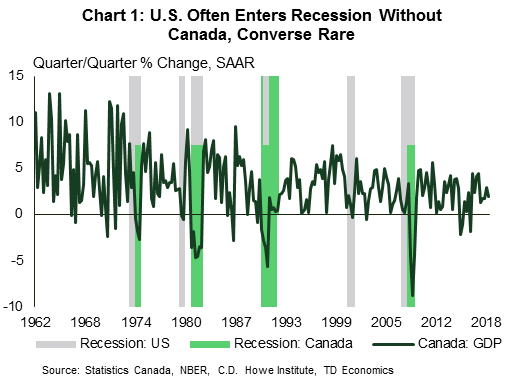

History shows that a U.S. recession is a necessary (but not sufficient) condition for a Canadian downturn (Chart 1). Indeed, not since the government policy-induced recession of the Korean War era has Canada entered a ‘true’ recession without the U.S. also in the same predicament. This 1950s incident is not even captured in Statistics Canada’s current historical series for quarterly GDP and given the unique situation and cause, bears little informative value for the current context.1

Thus, even though there is a precedent, a Canada-only ‘true’ recession is effectively unheard of. But, as the well-known disclaimer says, past returns are not necessarily an indicator of future performance. One potential reason not to dismiss this risk is that the “escape valve” provided by a floating currency and the external sector may not be functioning as strongly as it once was. It was a softer currency and rising exports that helped Canada remain in positive territory during the 1998 Asian debt crisis, as well as the 2001 U.S. dot-com implosion, even as domestic demand softened markedly.

This brings us to the core message of this report. It is unlikely for Canada to enter a ‘true’ recession without the U.S., but a statutory or technical recession is a different story. 2015 is a helpful example of this. Over the 2015Q1 to 2016Q3, Canada saw three quarters of economic contraction (two back-to-back) and effectively no growth traction in between those periods. This ticked the box on the downturn having duration. But, importantly, the weakness was not widespread across industries or labour markets among the provinces, thus not qualifying as a ‘true’ recession.2 The 2015 episode marks a technical recession in our books. This was a rare occurrence considering that three other periods of weak economic momentum (1986, 1995, and 2001) failed to meet the two-quarter contraction bar of a technical recession. This is true even in instances where the U.S. economic cycle was formally characterized as a ‘true’ recession (2001) by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

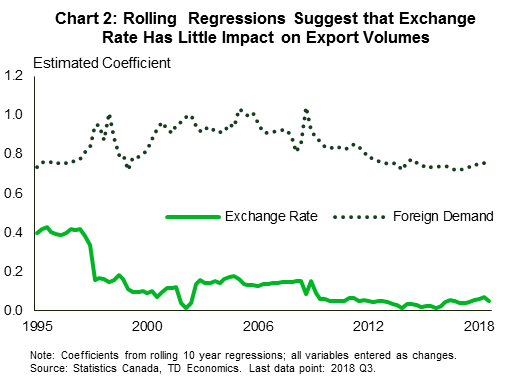

Although the 2015 experience is rare, it would not surprise us to see more of these experiences in the future for a couple of reasons. To begin with, simple rolling regression results indicate that the relationship between the currency and exports has weakened materially, particularly since the late 1990s (Chart 2). To be sure, the evidence still shows that a weaker loonie should give a short-term boost to exports, but the effect is nowhere nearly as pronounced as it has been in the past.

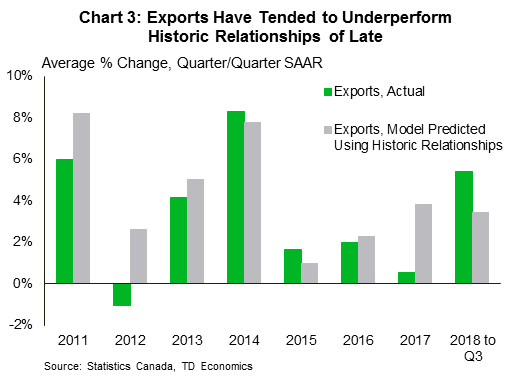

Further analysis suggests that even the rolling regression results for foreign (largely U.S.) demand may be overstating the case, or at least oversimplifying. Drilling into Canadian export performance post-crisis, we’ve seen a tendency for exports to underperform their historic relationship with foreign demand, to the order of about 1 percentage point on average (Chart 3).3 Slicing observations into smaller and smaller pieces is getting into data mining territory, so a grain of salt is need. But, there does appear to be evidence that past macroeconomic relationships have weakened.

With evidence that the external sector ‘escape valve’ may not be operating quite as strong as it once has, it would seem short-sighted to ignore the risk of a downturn simply because the U.S. economy appears healthy.4 Again, we should remember our definitions: the foreign demand channel is weaker, but it hasn’t vanished. The trade and currency dynamic within in a ‘true’ recession (as unlikely as that occurring in Canada alone is), would still place a floor under the Canadian economy. Thus, we are again talking about the risk of ‘only’ a statutory recession. Importantly, the data and trends don’t even support this outcome at the moment.

Canada broadening its horizons

Although Canadian goods exports (ex-energy) to the U.S. have been stagnant, shipments to other regions are showing some promise. Geography and other factors mean that the U.S. will always be a key factor behind the strength of Canadian investment and exports, but other markets have become a little more important recently. Over the last two years, Canadian exporters have enjoyed increased access first to Europe, via CETA, and, from January 2019, many Pacific Rim South American nations via CP-TPP.

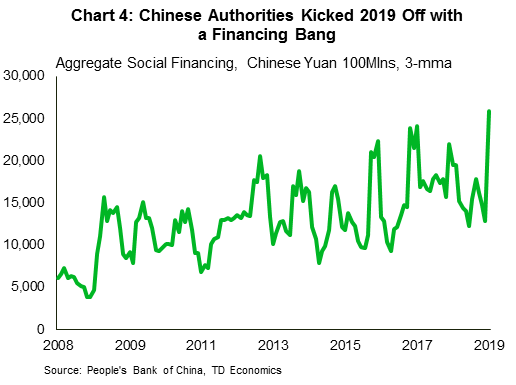

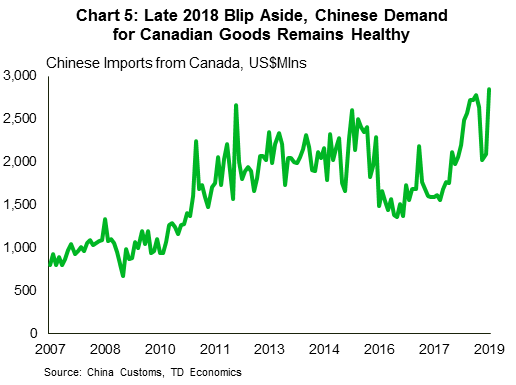

The near-term signals suggest more help may be on the way. A slowdown in China has been having direct knock-on impacts to Asian and European economies, with indirect impacts on Canada via reduced overall foreign demand. However, in recent months, Chinese authorities have made significant efforts to re-invigorate their economy. This has come in the form of eased reserve requirements for banks, and an increase in overall financing flows, even larger in scope than the stimulus introduced during the Global Financial Crisis (Chart 4). The surge of financing should make its way through the Chinese economy in the next two to three quarters, and, by extension, help support overall world exports through a virtuous cycle. Canada would benefit as demand throughout the Chinese supply chain rises, supporting global growth and lubricating the export flows with Canada’s new trade pacts in place. This comes in addition to the direct impacts of Chinese imports from Canada, which have been quite healthy of late (Chart 5).

Inventories piling up

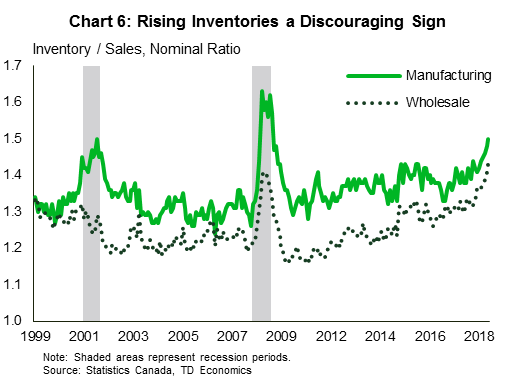

However, the key risk to Canada entering a technical recession or prolonged economic slump doesn’t stem from the external trade sector, but from domestic drivers. Standing out as a clear risk is the sharp inventory build up in the latter part of last year (Chart 6). Wholesale inventories in particular are concerning, popping up to an all-time high in December 2018. While not quite as dramatic, the manufacturing sector has also seen a rapid rise, as sales fell in each of October, November and December.

Diving a bit further into the data reveals a handful of sectors that are on the bubble. Most notably, wood product manufacturers have seen inventory levels climb rapidly, likely due to softness in both Canadian and U.S. housing markets and ongoing trade issues. Early data suggests some upside to activity in these markets, but for Canada in particular, the path forward is far from certain. Elsewhere, the ratio is elevated at present among plastics and rubber product manufacturers, as well as primary metal manufacturers. Further demand weakness could lead to an adjustment on the production side, sapping economic output. Clearly the risks to the sales side are tilted to the downside, so the signal coming from this data is clear. With increases concentrated in a few industries, the risk looks more like a statutory recession, not a true one.

Domestic challenges significant

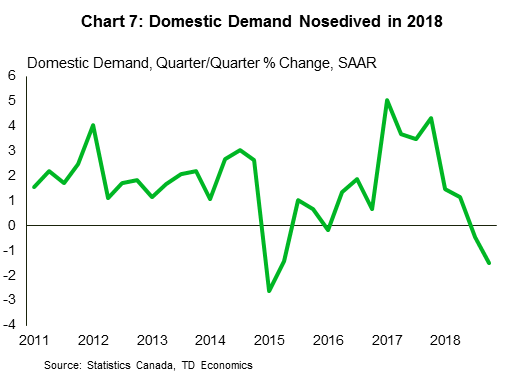

As inventories have built up, final domestic demand has been slowing, decelerating markedly over 2018 following a strong 2017 (Chart 7). Domestic demand has now contracted for two straight quarters, the first time since 2015, and with business investment stubbornly weak. However, domestic demand is dominated by consumer spending, which is in large part of function of the credit cycle. This cycle has already turned into a decelerating phase.

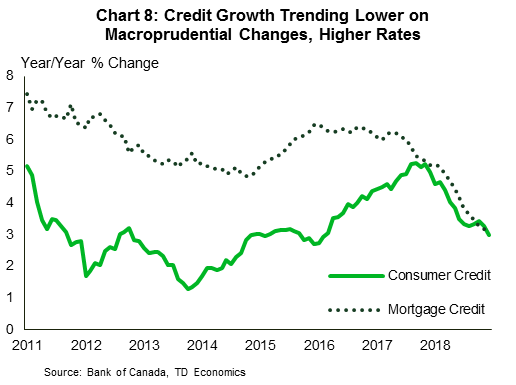

Both consumer and mortgage credit have been trending lower, with the latter impacted by changes to mortgage underwriting rules that sapped borrowing demand last year (Chart 8). Consumer credit actually contracted on a month-on-month basis for the first time since 2011, in December 2018.

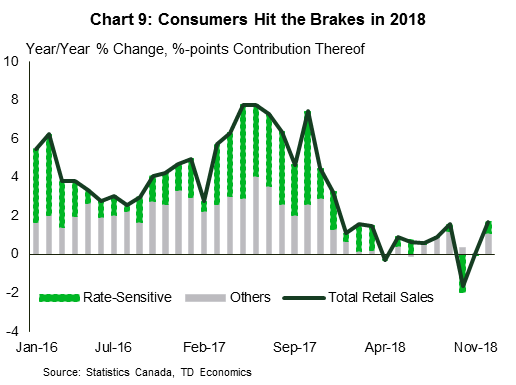

Monthly noise aside, all the signs are in place for a ‘soft’ deleveraging cycle, in which credit growth remains in positive territory but trends below household incomes. The result has so far been what we expected: a generalized slowing in consumer spending, particularly in spending on interest rate sensitive categories, such as autos and those categories linked to housing, such as furnishings (Chart 9).5 Retail sales don’t capture the complete spending picture: service spending takes the lion’s share of consumer dollars. But, it can be a swing factor, and serves as an early bellweather of consumer activity. This is sending a clear softening signal, reducing the economic ‘cushion’ in the event of a shock.

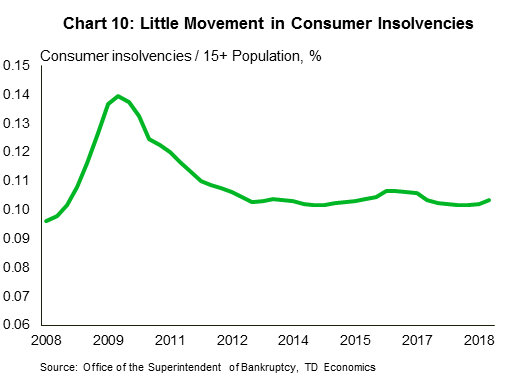

If there’s an area where late cycle dynamics have not taken hold, it is within consumer insolvencies. A much discussed rise in consumer insolvency activity in late 2018 looks more like a blip once it is put into perspective (Chart 10). Our analysis suggests that it takes a deterioration of labour markets to get a meaningful increase in insolvencies, and even then, the impact comes with about half a year’s lag, meaning this data is not a leading indicator of a cycle.

Labour market still a bright spot

Turning back to the insolvency picture, the reason Chart 10 doesn’t look worse is likely because, in aggregate, Canadian labour markets have remained solid (see report). Roughly 195k net jobs were added over 2018, with a further 67k to kick off 2019, according to the labour force survey. The less timely payrolls survey paints an even rosier picture, indicating that more than 320k net payroll positions were added in 2018, even including December’s modest pull-back.6 The result is an unemployment rate near 40 year lows, alongside record high participation rates.

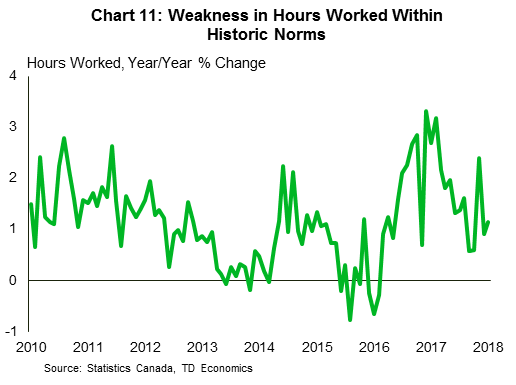

As strong as labour markets have been, there are nevertheless two flies in the ointment. First, wages have been decelerating, a somewhat perplexing development. At least part of this appears due to weakness in Alberta, where past oil sector shocks were still reverberating in labour markets even before late last year’s heavy oil pricing crunch. As such, this should reverse, and we have seen some very tentative evidence of this in the January data. The second fly is recent weakness in aggregate hours worked, which fell in both December and January. This data can be useful as an early indicator of economic weakness (in contrast, the unemployment rate tends to be a coincident to slightly lagging indicator), but the fortunate news is that this data can also be quite volatile, with a few months of weakness hardly atypical even during robust expansions. Indeed, the current reading remains well within historic norms (Chart 11). Again, we should not be dismissive of the risks, but scale matters, and current readings are well shy of any recessionary territory.

Real estate set for a slog

Falling somewhere in between the credit cycle and still healthy labour markets are Canadian real estate markets. Regional divergence remains the theme, with markets in the west still soft, Quebec hot, and Ontario/GTA falling somewhere in between. This is reflected in the most recent data, which saw home sales rise 3.6% in January 2019 (m/m, SA). As discussed in our December housing outlook, we don’t expect January’s performance (which came after several months of falling sales) to be repeated. More likely is a gradual slog upwards, with activity and price growth held back by still stretched affordability, rising borrowing costs, and in the case of prices, a relatively full supply pipeline in Vancouver and to a lesser extent, Toronto.

So, why not a worse outlook, or even an outright crash? Two reasons: first, fundamental demand is still strong, particularly in key markets. Canadian population growth hit a record in 2018, and government targets will see continued strong inflows, with many new Canadians supporting demand in the ‘landing pad’ cities of Toronto and Vancouver, where populations rose at least 130k and 40k respectively last year.7 Second, the change in tone from both the Bank of Canada and the U.S. Federal Reserve in light of late 2018 developments (market volatility, energy sector challenges, global growth deceleration, etc.) provides some additional market sentiment support in the form of lower than previously expected borrowing costs.

Ultimately, the theme of this note is echoed in this sector. The outlook is for modest activity that leaves less of a growth-cushion in the event of a negative shock, but growth nonetheless. Less buffer alone does not a downturn make, and as it stands, the situation in housing markets points to elevated risks, not to a downturn.

Don’t rule out psychology

If there is a core message to this analysis, it is that yes, risks to the Canadian economy are elevated right now, and the risk of a near-term contraction in activity cannot be ruled out given that our low growth outlook allows little room for error. But importantly, we do not see a strong enough signal to call a downturn, and even if we do get negative prints on GDP growth, the most likely outcome is a shallow, technical recession, not a ‘true’ downturn.

If there is a caveat however, it is that we cannot ignore risks related to consumer and market psychology. As discussed previously by our Chief Economist, Beata Caranci, negative sentiment can result in a feedback loop, manifesting itself in a “Beetlejuice recession” where growth turns negative simply because people expect it to and act accordingly. For Canada in particular, the risk is probably greatest around household debt and the potential for deleveraging. For an individual household, it may make sense to reduce spending and focus on saving, but if many households take the same approach, the result is, on aggregate, a contraction in economic activity. This is called the paradox of thrift, where individually rational behavior is irrational in aggregate.

A key question is thus how likely is such an outcome? Or, put differently, are negative narratives, whether media or otherwise, sufficient to spur action? While the labour market is doing a lot of heavy lifting in this analysis, it nevertheless appears to be the linchpin for this behavior as well. So long as labour markets remain healthy across most of the country (and importantly, the recent softness in aggregate hours worked proves temporary), it is challenging to envision a sentiment-led retrenchment in consumer spending. That said, the risk cannot be dismissed, and this channel would likely work as an intensifier. As the experience of the U.S. over 2009/2010 shows, consumer deleveraging led recessions tend to be longer and more pronounced. Even absent a downturn, slower growth deleveraging periods can be quite lengthy, lasting about five years on average.8 However, context matters. In the unprecedented event that Canada experiences this downturn on its own, adjustment channels, even in their diminished state, should help reduce the burden – it would likely take a simultaneous U.S. downturn to get to the worst case scenario.

Canadian risk intensity idiosyncratic

The current situation in Canada has echoes of 2015, but with a few important differences. For one, the current shock to the energy sector is clearly temporary, and price dynamics have so far exceeded expectations to the upside. Secondly, the energy sector has, as a result of past shocks, declined in overall importance to the Canadian economy, and at the same time (and more encouragingly) driven efficiency gains over this time, reducing the cost of production. Conversely, the economy received 50bp of policy interest rate cuts in response to the 2014/2015 oil price shock, reducing the impact by spurring growth in other sectors, notably housing. The result was two consecutive quarters of economic contraction and about a year and a half of stagnation, but without enough breadth and leakage into the labour market to qualify as a ‘full’ recession nationally.9

In contrast, part of the current growth slump this time is by design on two fronts. First, curtailments in oil production shaved an estimated 0.5 percentage points off GDP growth in 2018Q4, with a 1.1 percentage point drag expected in 2019Q1. If not for this, we probably wouldn’t be having this discussion in the first place, because growth would otherwise hang closer to the 1.0-1.5% range: below trend, but not dramatically so. Second, the impact of past interest rate increases was combined with macroprudential policy on household finances. Either of these levers can be altered in the event of a large disappointment in the data to mitigate the downside, as was the case in 2015.

Bank of Canada willing to adjust course

As one of the key stewards of the economy, central banks are constantly monitoring developments and adjusting monetary policy accordingly. The Bank of Canada is no exception. As the current growth slump became evident, the Bank’s relatively hawkish tone of communication gave way to a more dovish bent, and the January Monetary Policy Report saw their 2019Q1 growth tracking marked down to 0.8% q/q, only modestly above our current tracking. Governor Poloz and company are seeing the same signals that we all are, and has shown willingness to adjust course.

For now, the central bank is in wait-and-see mode, with communications still emphasizing an eventual return to “neutral”, currently defined as a policy interest rate within the 2.50% to 3.50% range (See Poloz’s recent speech, for instance, and our commentary). Even this may be too lofty a goal. We expect the policy rate to gradually move towards the 2.00-2.25% range, reflecting our relatively more modest assumptions on trend productivity growth, as well as the impact of B-20 mortgage regulations (see commentary). The B-20 changes have, in effect, already tightened policy by 200bps for a sizeable segment of the population. Taking the relative size of the mortgage credit market into account suggests that even today (at 1.75%), the policy interest rate is already within the Bank’s ‘neutral range’ once the mortgage stress test is taken into account.

With all of the evidence that Canada is facing its own pressures at present, narratives that see the Bank of Canada sending the economy into recession by following the Federal Reserve don’t make any sense. All forecasts are conditional, and our Bank of Canada outlook is no different, with preconditions to action discussed in our recent Dollars and Sense. A return to ‘normal’ economic growth is a key precondition for higher rates. The Bank of Canada’s mandate is to set monetary policy appropriately to achieve its Canadian inflation target, not to maintain some spread to a foreign interest rate. We expect the Bank of Canada to react to Canadian economic developments, positive or negative, appropriately, even if Canadian conditions diverge from our peers and major trading partners.

Bottom Line

There is no denying that Canada is facing a perfect storm at present. A more intense-than-expected moderation of economic growth came just as North American commodity markets sent Canadian heavy oil prices lower, resulting in an additional near-term growth shock as producers curtailed output. All of this is taking place against a backdrop of still highly levered households facing rising borrowing costs for the first time in a generation. However, a growth slump is not a recession, and there are marked differences between a slump, a technical recession, and a true recession.

That said, the risks are nevertheless significant. Canada’s unique position tells us that we can have negative growth without the U.S. needing to also be in contraction. The current growth slump means that we have less ‘buffer room’ in the event of a shock. Thus, we believe that Canada is currently at a greater risk of a period of weakness than the U.S., a situation that echoes the 2015 experience. It remains most likely that the current slump will give way to a modest growth recovery in the second half of 2019, helped by the end of major energy sector curtailments. Getting from here to there will be no easy feat, and if current weakness in household credit growth is joined by labour markets, a technical or statutory recession would be on deck. However, a ‘true’ recession would probably still require a U.S. downturn – an unlikely event, at least in the near term.

End Notes

- Synchronization is of course not perfect: the U.S. experienced more prolonged contractions in the mid-1970s and 2009 recessions, while Canada had a much longer downturn in the early-1990s.

- Obviously for those in the most impacted regions, this period was recessionary.

- The 2018 performance is also somewhat misleading as much of the strong performance came in the second quarter as earlier disruptions in the auto and energy sectors resolved themselves.

- The topic of the risks to the U.S. economy is large enough to justify its own report. Put succinctly, our analysis suggests a moderating pace of growth this year, but does not envision a U.S. downturn in 2019.

- Rate sensitive sectors are: automobile dealers, furniture and home furnishings stores, electronics and appliance stores, and building material/garden equipment and related stores. Note that the December y/y uptick is largely due to a base effect from soft spending in 2017.

- Differences in survey methodologies include the treatment of multiple job-holders and self-employment, among others.

- This data is only provided by Statistics Canada on a 3 month moving average basis, thus these figures are approximate.

- See for instance, this 2015 IMF Working Paper.

- Again, this period was obviously recessionary for the energy producing regions.