- Financial stress is on the rise turning focus yet again on whether China is heading for a deeper financial and economic crisis.

- While we do see a rising risk of this happening (25% probability), our baseline scenario remains that China has the tools to avert such an outcome and will use them to the extend needed. Yet, due to the recent weak data and rise in financial stress we have revised down our forecast to 4.8% growth this year and 4.2% in 2024.

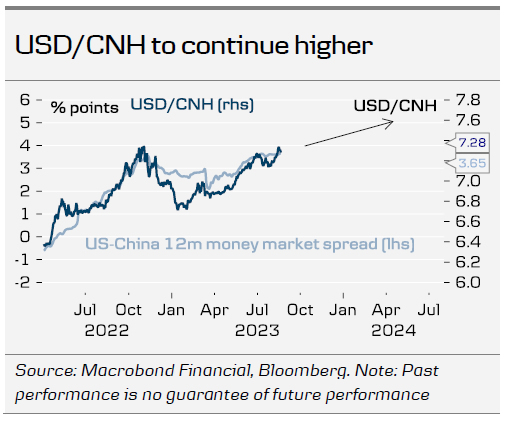

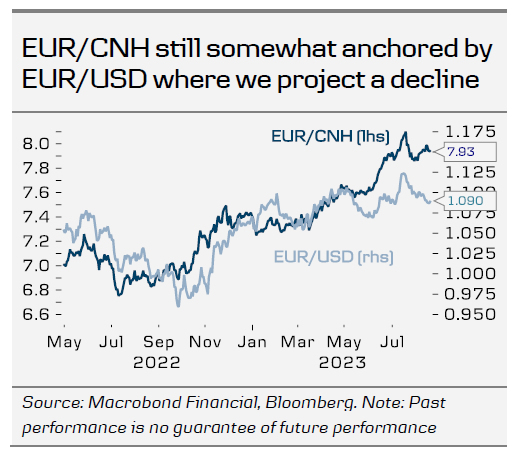

- We have lifted our forecast for both USD/CNH and EUR/CNH taking the new weaker growth outlook as well as rising risks into account. We now project USD/CNH to hit 7.60 in 12M up from 7.40 previously.

Headwinds on the rise again – lower GDP growth

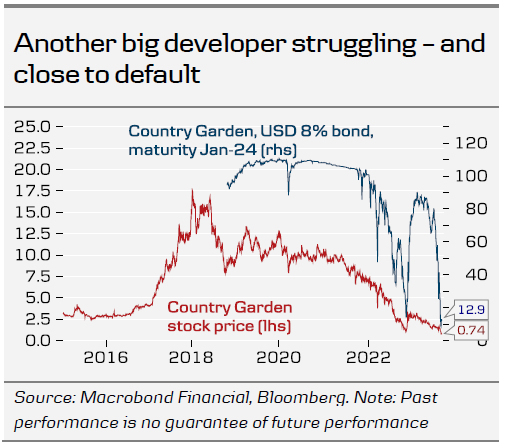

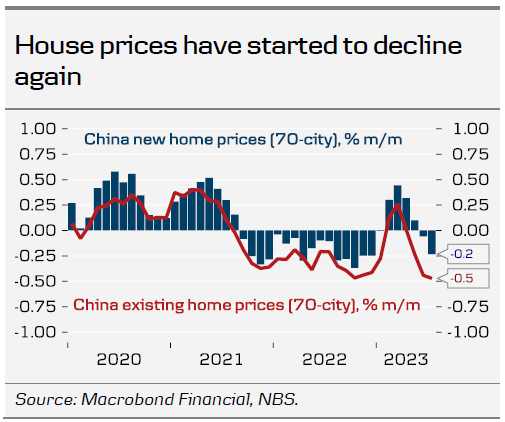

As we wrote about in China holiday wrap-up – part three: risks of a financial crisis resurface, 14 August, financial stress has increased lately with another major developer, Country Garden, at brink of default and contagion to the shadow banking system increasingly visible. On top of this economic data has disappointed across the board with both consumer spending, home sales and exports undershooting expectations. Taking these developments into account we revise down growth to 4.8% this and 4.2% next year.

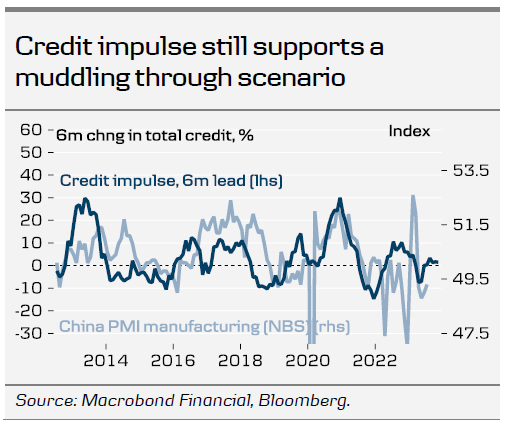

In this baseline scenario we assume policy makers to step up stimulus as broadly signalled following the Politburo meeting in late July and to take more measures to improve financing channels for developers, lift home sales. We also expect them to provide the necessary lifelines to local governments and facilitate a restructuring of major shadow banking entities in distress, such as Zhongzi Enterprise Group. Our assumption is that they will still strive to reach the 5% target and do what is necessary to at least put a floor under growth so it does not fall below 4-4½%.

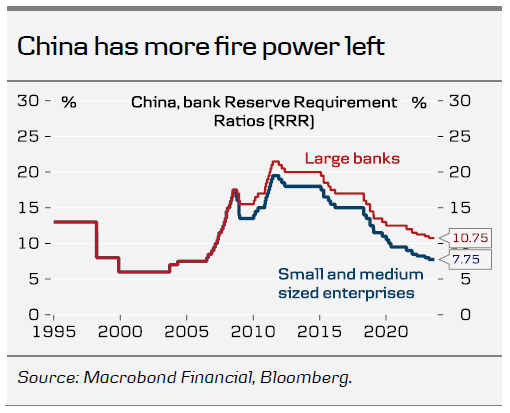

So which tools does the Chinese government have at its disposal to fight this crisis? First, it can follow through on the “forceful stimulus” it already vowed to do in late July in order to lift demand for private consumption, housing and infrastructure investments, see China holiday wrap-up – part 2: Stimulus and private sector plan lift Chinese markets, 28 July. Second, it can increase funding channels for developers. On Friday, PBOC and financial regulators met with bank executives telling them to direct more lending to support an economic recovery. It suggests policy makers are increasingly concerned about the recent financial stress and as the big lenders are state-owned they have some control over the amount of lending. Third, they can cut Reserve Requirement Ratios (RRR) for banks to free up more liquidity to buy credit bonds and increase lending. The RRR for small and medium sized banks is 7.75% while it is 10.75% for large banks. Fourth, like in developed economies China could opt for quantitative easing (QE) with PBOC buying bonds directly in the market. This would serve as a strong signal that they step in as lender of last resort. Why are they not doing it yet? Probably because the other tools have not been exhausted yet and they would rather cut RRR and let state banks do the buying.

Why are policy makers not already doing more?

That is a question often asked these days and it is also what causes concern to us. There are several options.

First, we do not know yet if they actually are preparing to do bigger stimulus but are just slow in implementation as the slowdown during spring came as a surprise. The policy signal from the Politburo in July did suggest a more forceful response. But the action has been underwhelming so far with only moderate rate cuts of 10-15bp. Still, it could be that they are brewing on other tools instead as they are concerned about cutting rates too much as it could add to the downward pressure on the yuan, which they are currently defending via stronger fixings and state banks selling dollars in the market. The jury is still out on how much stimulus is actually planned.

Second, it seems clear that Chinese policy makers have learned from the past mistakes of providing too much stimulus in a fairly uncontrolled manner as was the case in 2008-09. It led to a severe hangover with rising debt levels and wasteful investments. The risk is, though, that the pendulum has swung too much in the other direction and they don’t do enough to get ahead of the curve and turn the economy around.

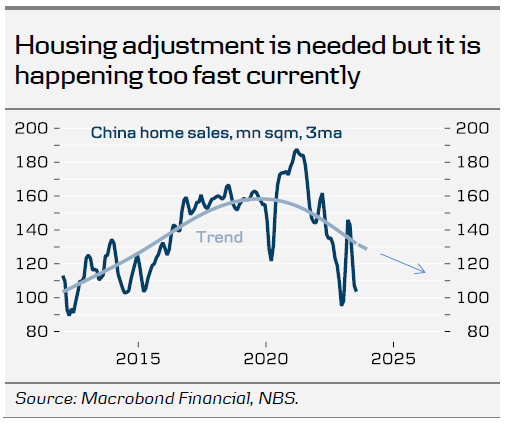

Third, Chinese leaders seem very keen on weaning the Chinese economy off the ‘addiction’ to a strong housing market, which has made many sectors over-reliant on continued growth in this sector. Households have 60% of their wealth in the sector. Developers have been riding the market with rising leverage for years and absorbed capital that would have been put to better use in the ‘real economy’. Local governments depend on land sales for a large chunk of their revenues. And ordinary businesses have sometimes bought property just to use it as collateral for loans and for investment. This is not sustainable and policy makers may see the situation as a necessary pain to adjust to a new world where capital is allocated to more efficient sectors, not least high-tech manufacturing and tech. The risk is, though, that the whole economy crashes if Chinese leaders let the adjustment happen too fast. Also, it undermines their attempt to restore consumer confidence and make consumers a key driver of overall demand. So they will likely step in with more support but they will probably not do more than is absolutely necessary.

Risk scenarios – financial stress escalates triggering deeper crisis

With the fine balancing act of on the one hand finally getting rid of moral hazard and the economy’s ‘housing addiction’ and on the other hand not triggering a deeper crisis, there is a risk that policy makers miscalculate and fall too far behind the curve so that the financial snowball that is rolling now gets too big to stop.

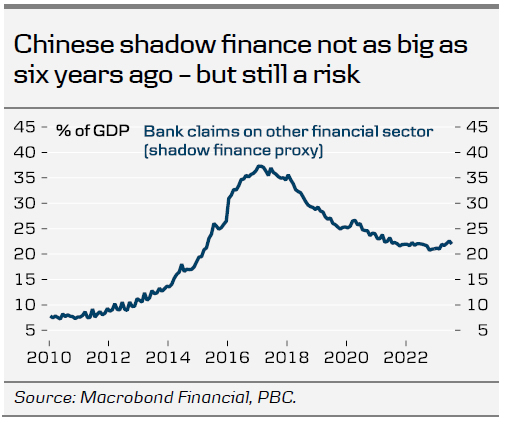

One way this could happen, would for example be if financial confidence in Wealth Management Products (WMP’s) erodes sharply and causes a ‘bank run’ on these savings products. WMP’s are basically a kind of deposits held in shadow banks that yield a higher rate than in ordinary banks, but also has much higher risk. Any losses are transferred directly to the depositor (buyer of the WMP) rather than the ‘bank’, but often times buyers of the products are not alert to this feature. If money is pulled out of the system rapidly, the financial stress could become so high that the government is unable to stop it – at least initially. The shadow banking system is already showing cracks and a few more bad stories could risk triggering a run on the system. One problem in these products is a classic maturity mismatch as they can be exited with short notice (3 months for example) but they finance loans with longer maturities – and with some of them being loans to developers. If the money is pulled out, it would not only hurt developers but also other companies that get funding through these products. It could thus trigger defaults more broadly as it cascades through the economy. On a positive side, shadow banking does not play as big a role as 6-7 years ago as the government realized the risks and started a crackdown. But it is still close to 25% of GDP. And in combination with other risks, such as those from local government debt (around 50% of GDP), and a possible deeper housing slump, the situation warrants close monitoring.

In a financial crisis scenario, growth could drop much further in the short term, but policy makers would likely step in as ‘lender of last resort’ via PBOC and state banks to avoid a continued significant credit crunch. Stimulus would also be scaled up markedly. Nevertheless short term pain would likely be felt across the economy before the government’s rescue action would have its’ impact. A bit like the European debt crisis where the ECB refused to step in as lender of last resort until it threatened the whole euro system, and they stated they ‘would do whatever it takes’. From there on the crises was more or less over. Why did the ECB wait so long? Same reason as in China. Moral hazard issues suggesting that you should only come to the rescue when there is no other option. Investors need to bear pain along the way to avoid too much risk taking again in the future.

It is hard to put numbers on these things as it could unravel in many ways but to give a sense of what we think of, we see both a ‘mild crisis scenario’ being possible where growth drops down to 3% for 6-9 months before the rescue action turns things around and a ‘hard crisis scenario’ that leads to outright negative growth for around 6-9 months. Currently we put the probability of a ‘mild crisis scenario’ at 15% and a ‘hard crisis scenario’ at 10% with a total risk of some crisis scenario summing up to 25%.

USD/CNH to continue higher

Based on the downward revision to our baseline growth scenario, we now also see USD/CNH moving even higher than in our current forecast as monetary policy divergence continues and downside risks weigh on the CNH. We now look for the cross to reach 7.70 in 12M (previously 7.40). For EUR/CNH, it implies a broadly flat level around 7.95 for the next 6-12 months based on our projection of a further decline in EUR/USD. The risk is skewed to the upside, though, as we see a higher probability of Chinese activity surprising to the downside still adding more downside on the CNH.